An emerging threat to Lakeland rivers? Pharmaceuticals in the water

A new report has found concerning levels of pharmaceuticals in National Park rivers. Eileen Jones digs into the Lakeland data.

A new report on the state of rivers in England’s national parks – including the Lake District – has revealed widespread contamination from pharmaceuticals.

Drugs for treating diabetes, depression and high blood pressure, along with antibiotics and caffeine, were found in river water at 52 of 54 locations monitored across all ten national parks in England. And while sites in the Lake District were some of the least polluted of those monitored, 11 pharmaceuticals were detected in the Park, the highest concentrations at a tourist hotspot in Coniston.

The study, undertaken by the University of York, found pharmaceuticals at levels of concern for the health of freshwater organisms, and for humans who come into contact with the water.

Professor Alistair Boxall, from the Department of Environment and Geography, who led the study, said the potential impacts on human health should not be understated: “The occurrence of some antimicrobials are above safe levels for selection of resistance in bacteria and this could be a contributor to the global antimicrobial resistance crisis.” As such, open water swimmers in polluted water bodies could be raising their risk of antibiotic resistance.

The worst performing national park was the Peak District, with 29 ‘Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients’ (APIs) detected in rivers. Water bodies in the Yorkshire Dales were least impacted, with just 7 APIs. Eleven APIs were recorded in the Lake District.

Scientists are now working with the Campaign for National Parks (CNP) to put pressure on Government, local authorities and the water industry to improve monitoring of pharmaceuticals in national parks. They want to see further investment in treatment technologies to protect rivers in the parks, and further exploration of the impacts of pharmaceuticals on the health of park ecosystems.

Of particular concern is a lack of data about API presence in water bodies, and how different APIs react when combined together. “Due to a lack of data for APIs in national parks, we have no grasp of the level of ecological risk that the substances pose,” said Professor Boxall. “At many locations monitored, a complex mix of APIs was detected, which raises the potential for toxic interactions that might exacerbate their impacts.”

Pharmaceuticals in Lakeland rivers

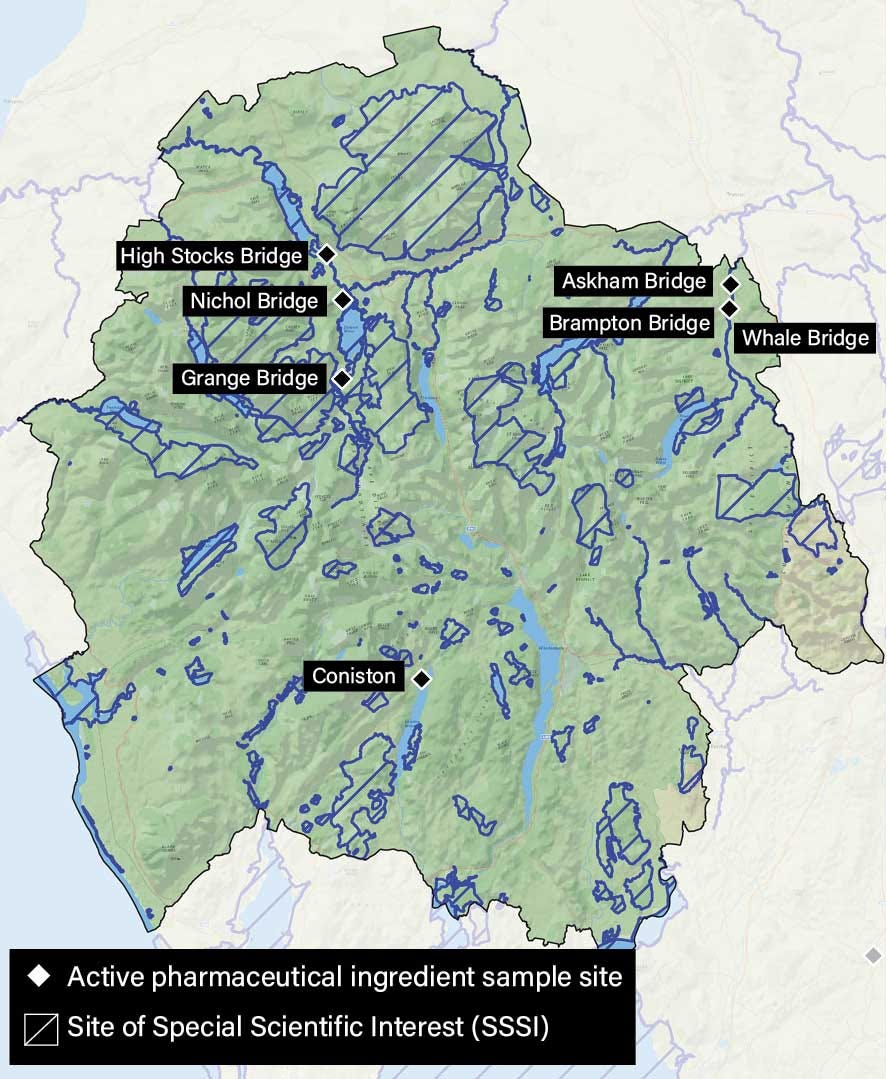

In the Lakes, sampling was conducted at eight sites. In the north Lakes these were at Brampton Bridge, Askham Bridge and Whale Bridge on the River Lowther; at High Stocks Bridge and Nichol Bridge near Portinscale on the Derwent, and Grange Bridge in Borrowdale. South of the Raise, samples were taken at two sites near Coniston, where Church Beck enters the lake near the popular Bluebird Café and boat landings.

The pharmaceutical found at highest concentrations throughout the Lake District was the stimulant caffeine, likely passed into rivers via untreated urine. At Coniston, samples taken in the summer found the highest number of different chemicals, as well as the highest summer concentration of pharmaceuticals.

It was here that scientists found evidence, along with caffeine, of diltiazem, used to treat blood pressure, the anti-epileptic treatment carbamazepine, antihistamines cetirizine and fexofenadine, the anti-depressant drug desvenlafaxine, metformin, which is used to treat Type 2 diabetes, and the anti-convulsant drug gabapentin.

Only the Brampton Bridge samples showed no evidence of pharmaceuticals, while at Whale Bridge the one drug detected – in significant concentrations – was sulfadiazine, an antibiotic typically used to treat farm animals.

The origin of pharmaceuticals

Pharmaceutical substances are most often released into the natural environment via urine after a person has consumed medicine. Other reasons include the improper disposal of unused medicines and the use of medicines in agriculture.

Professor Boxall explained that most work on pharmaceutical pollution in the UK had previously focussed on urban rivers. “This study is unique as it explores areas where we might expect low levels of pollution, and we have shown that this is not the case,” he said. “Our national parks are hotspots for biodiversity and essential for our physical health and mental well-being, so we need to act swiftly to protect these irreplaceable environments and ensure the health of wildlife and visitors alike.”

He added: “There are several reasons why these rivers are more polluted than you might expect, including lower dilution [where lower river flows in the upper reaches of a catchment mean pharmaceutical levels are proportionally higher than downstream], lower connectivity to sewage treatment systems, older and less high-tech treatment of sewage, and seasonal population surges due to tourism. It is the fact that they come together in often remote and fragile places that make our national parks particularly vulnerable.”

While modern urban treatment plants are able to extract pharmaceuticals from waste water, few in national parks are built to the same technical standard. They are also subject to stormwater overflows, where sewage is discharged into water bodies without treatment – a practice that Save Windermere campaigner Matt Staniek is campaigning to end.

Alongside ageing and often insufficient sewage treatment plants, national parks have other specific issues to deal with, including huge seasonal fluctuations in population numbers, with treatment plants often ill-equipped to deal with peak population surges (the Lake District has around 39,000 permanent residents, and receives more than 18 million visitors each year). This puts additional strain on treatment plants.

Andrew McCloy, Chair of Trustees at the Campaign for National Parks said: “These findings are an indictment of the current state of our rivers and water bodies, threatening the health not just of people and communities, but also wildlife and ecosystems.”

Reducing pollution

Action to remove pharmaceuticals from rivers must take place at local, regional and national levels. Caitlin Pearson of the West Cumbria Rivers Trust, which collected some of the water samples, outlined work the charity is doing to reduce pollution: “We support farmers to reduce runoff by creating riparian buffer strips [long grass/woodlands next to streams that filter runoff], planting trees, fencing to keep livestock out of streams and rivers, and improving soil conditions. These all reduce inputs of agricultural pharmaceuticals.

“We’re working with United Utilities to look at the potential to reduce the chance of wastewater treatment plants becoming overloaded – and hence emissions from combined sewer overflows.

“And working with other partners, we have recently been successful in getting Derwent Water designated as a bathing water, which means it will be tested throughout the bathing season by the Environment Agency.”

Members of the public can also take action to lessen their contributions to pharmaceutical pollution. “We all get caught short sometimes when we’re out and about,” says Caitlin, “but make sure any wild wees are away from watercourses.”

“More importantly, take care of what you flush down the toilet. Take unused medicines back to the pharmacy. Private sewage treatment systems need looking after properly. Even if your property is on mains sewerage, many of the places people enjoy visiting such as campsites, holiday cottages and cafés may be on private systems, so people should follow any instructions about what can and can’t be flushed.”

Dave Greaves, conservation officer for the Eden Rivers Trust, which also helped sampling, argues the most significant driver of change will be at national level: “We need to advocate for policies that require all wastewater treatment facilities, including those in rural and protected areas, to adopt secondary and advanced treatment technologies that can remove pharmaceuticals from wastewater. We need to push for ongoing monitoring and research into the presence and effects of pharmaceuticals in natural environments, particularly in vulnerable ecosystems like national parks.”

Andrew McCloy agrees: “You would expect our national parks – places of exceptional beauty that are designated for the nation – to receive the highest level of protection, but this report shows water pollution is rife even in our most precious locations.

“The infrastructure and systems in place are not fit for purpose. We have let profit come before protection in the water industry.”

Eileen Jones is a freelance journalist and author of Loughrigg: Tales of a small mountain and How parkrun changed our lives.

The report comes ahead of a national protest on 26 October. The March for Clean Water is a one-off event in London organised by River Action – a broad alliance, supported by, among others, Surfers Against Sewage, the RSPB, Greenpeace, the Clean Water Sports Alliance, the Angling Trust, and the Nature Friendly Farming Network – to petition the government for clean water throughout the UK.