Arthur Ransome and the 'great frosts' that froze Windermere

To celebrate the release of a new Christmas jigsaw puzzle from Inspired by Lakeland, Paul Flint chronicles the great frosts of the late 19th century, as described by Arthur Ransome

“Softly, at first, as if it hardly meant it, the snow began to fall.”

So closes chapter five of the fourth book in Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons series, Winter Holiday – a title for which the author had an enduring soft spot.

The words not only hold the promise of adventure for the Walkers and Blacketts – whose Lakeland playground is transformed into the Arctic – they also set the scene for a tale that captures a moment of happiness from Ransome’s childhood, and document a series of ‘great frosts’ that – in a warming world – seem consigned to history.

Although set chronologically in around 1932, Winter Holiday has its genesis, as do many of Ransome’s books, in boyhood holidays spent in the Lake District. He later attended Old College, a preparatory school in Windermere, where, as a result of undiagnosed myopia he was most unhappy.

Fortunately for future readers, there were moments of joy, including when the 11-year-old scholar enjoyed a Windermere winter wonderland. His Autobiography describes the scene:

“Best of all I had the great good fortune to be at school at Windermere in February 1895 at the time of the Great Frost, when for week after week the lake was frozen from end to end. Then indeed we were lucky in our headmaster, who liked skating and wisely decided that as we were not likely to have such an experience again (the lake freezes over only about once in every thirty-five years), we had better make the most of it. Lessons became perfunctory.

After breakfast, day after day, provisions were piled on a big toboggan and we ran it from the Old College to the steep hill down into Bowness when we tallied on to ropes astern of it to hold it back and prevent it from crashing into the hotel at the bottom.

During those happy weeks we spent the whole day on the ice, leaving the steely lake only at dusk when fires were already burning and torches lit and our elders carried lanterns as they skated and shot about like fire-flies.

I saw a coach and four drive across the ice, and the roasting of an ox (I think) on Bowness Bay. I saw perch frozen in the ice, preserved as if in glass beneath my feet. Further, here was one activity in which I was not markedly worse than any of the other boys. On a frozen lake in the grounds of the three Miss Fords at Adel, a kindly foreigner, Prince Kropotkin, had guided my infant footsteps.

I had learnt to move on skates and was thus better off than most of the boys who had never skated at all. Those weeks of clear ice with that background of snow-covered, sunlit, blue shadowed hills were, forty years after, to give me a book called Winter Holiday for which I have a sort of tenderness.”

Newspapers in January and February 1895 were full of stories about the harsh winter Ransome describes.

The number of visitors that ventured north to enjoy frozen Windermere was extraordinary – even by today’s standards. On just one Saturday in February, 1895 around 15,000–20,000 people could be found skating, walking, riding and playing on the ice. Steam trains worked overtime to meet demand. The Furness Railway Company issued reduced price tickets, and on the Kendal to Windermere line hundreds of travellers evaded fares through sheer force of numbers.

A visitor from Manchester, writing in the Kendal and County News, painted an evocative picture of the ice-based festivities:

“As we descended towards the village that clusters round St Martin’s Church we saw people like black ants moving hurriedly to and fro upon the frozen level of the lake. Then the landings were reached, and such a scene presented itself as can only be seen in some old Dutch city in mid-winter.

The whole interspace between the land and the island was powdered white from the innumerable iron heels of the skaters. Here a pony with its jangling sleigh bells dashed along; there fond fathers pushed their little ones in perambulators. A hurdy-gurdy man-made music here, and yonder, on St Mary’s Holme, a brass band blew its best, and risked frozen lips and frost-bitten fingers in the process.”

Ransome not only plundered his boyhood memories for Winter Holiday, in January 1933 an adult Ransome took the Altounyan girls – who helped inspire Swallows and Amazons – skating on Tarn Howes. A diary entry of 28 January, 1933 reads: “Snow on the hills but only on the tops. Titty kicking with one leg. Taqui and Susie getting on pretty fast.” This scene finds its way into Winter Holiday, where the young explorers convert the low walls of an old building in the woods – almost certainly the remains of a bark peeler’s hut – into an igloo. It features in one of the book’s many pen-and-ink plates drawn by the author.

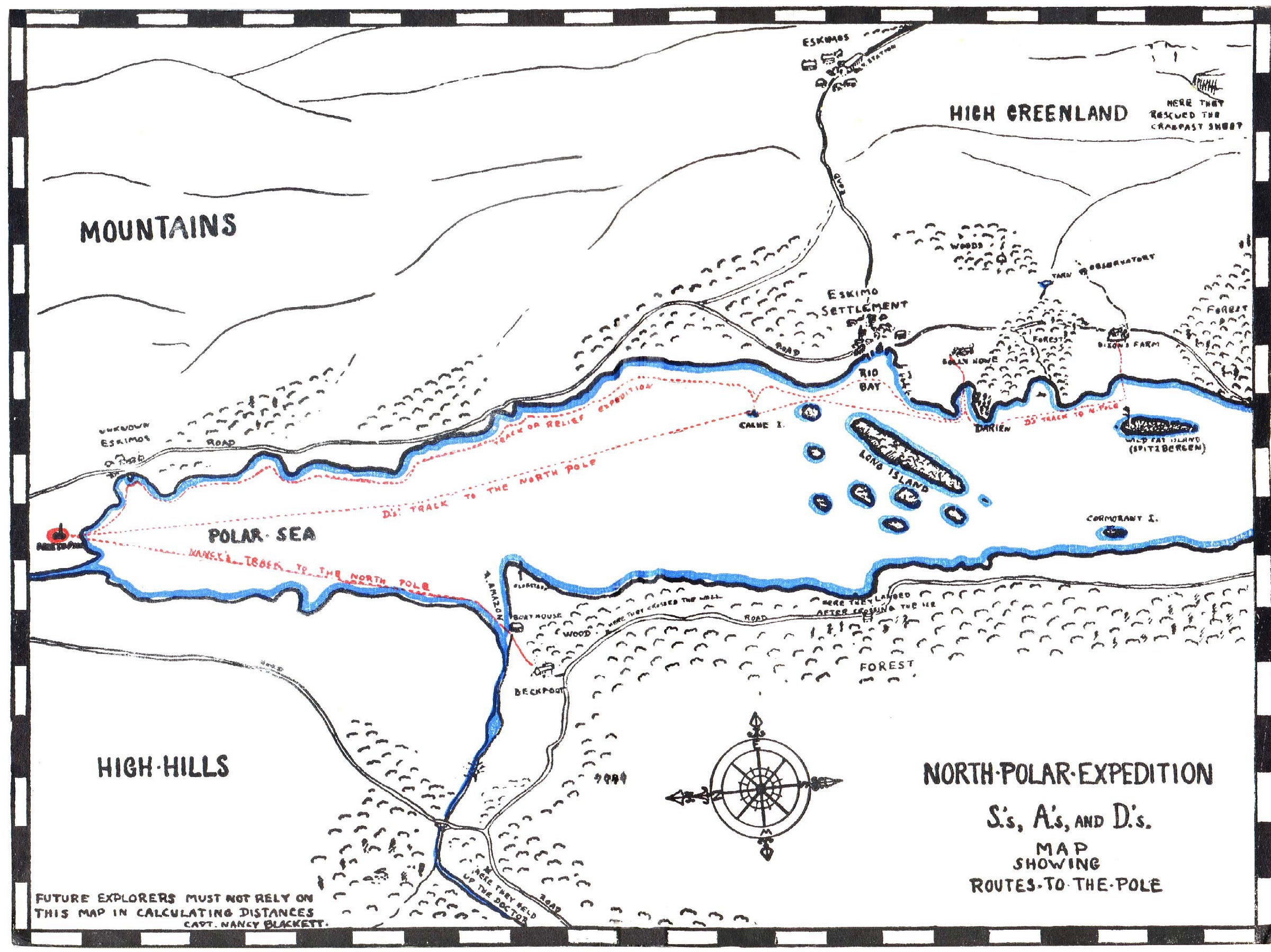

Ransome notes in Winter Holiday that during the great freeze hotels were hurriedly re-opened – and were busier than in summer. Farmer’s wife Mrs Dixon, who looks after Dick and Dorothea Callum – ‘the Ds’ – recalls how in 1895 she saw ice yachts rushing about the lake, racing for a silver cup, and coaches with four horses and horns blowing crossing the lake from side to side.

While there is drama and beauty in these evocative winter scenes, there is also death and danger:

“Look!” said Dick. “There’s a fish in the ice.”

It was a little perch, close to the surface, looking as if it were swimming in glass. The others turned back to see it and crowded round it, till a loud cracking of the ice gave them a warning.

“Spread out!” cried John.

The ‘frost fairs’ of the late 19th century had their basis in earlier events. A news report from 1784-85 describes how people made their way to frozen Windermere from nearby towns and villages. An ox was roasted near Rawlinson’s Nab, a two-and-a-half mile race was held for skaters, wrestlers wore caulkered clogs, a band from Kendal played music, and a finale was held at the Low Wood Inn.

Ransome’s claim that Windermere freezes “about once in every thirty-five years” was based on his own observations and historic knowledge of the area. We know from press reports that the lake froze in 1864 and, following the festivities in 1895, did so again in 1928-29, 1962-63 (when ice was over a foot thick in Bowness Bay) and, post-Ransome, partially in 1981-82. On each occasion vehicles crossed the lake and locals and visitors enjoyed skating at Bowness Bay, Waterhead and other locations.

Another occasion when Windermere seemingly froze is mentioned in Ransome family diaries. In January 1902 train loads of skaters arrived from London and a local boy – Hart-Jackson – was noted as having skated from Lakeside to Ambleside and back.

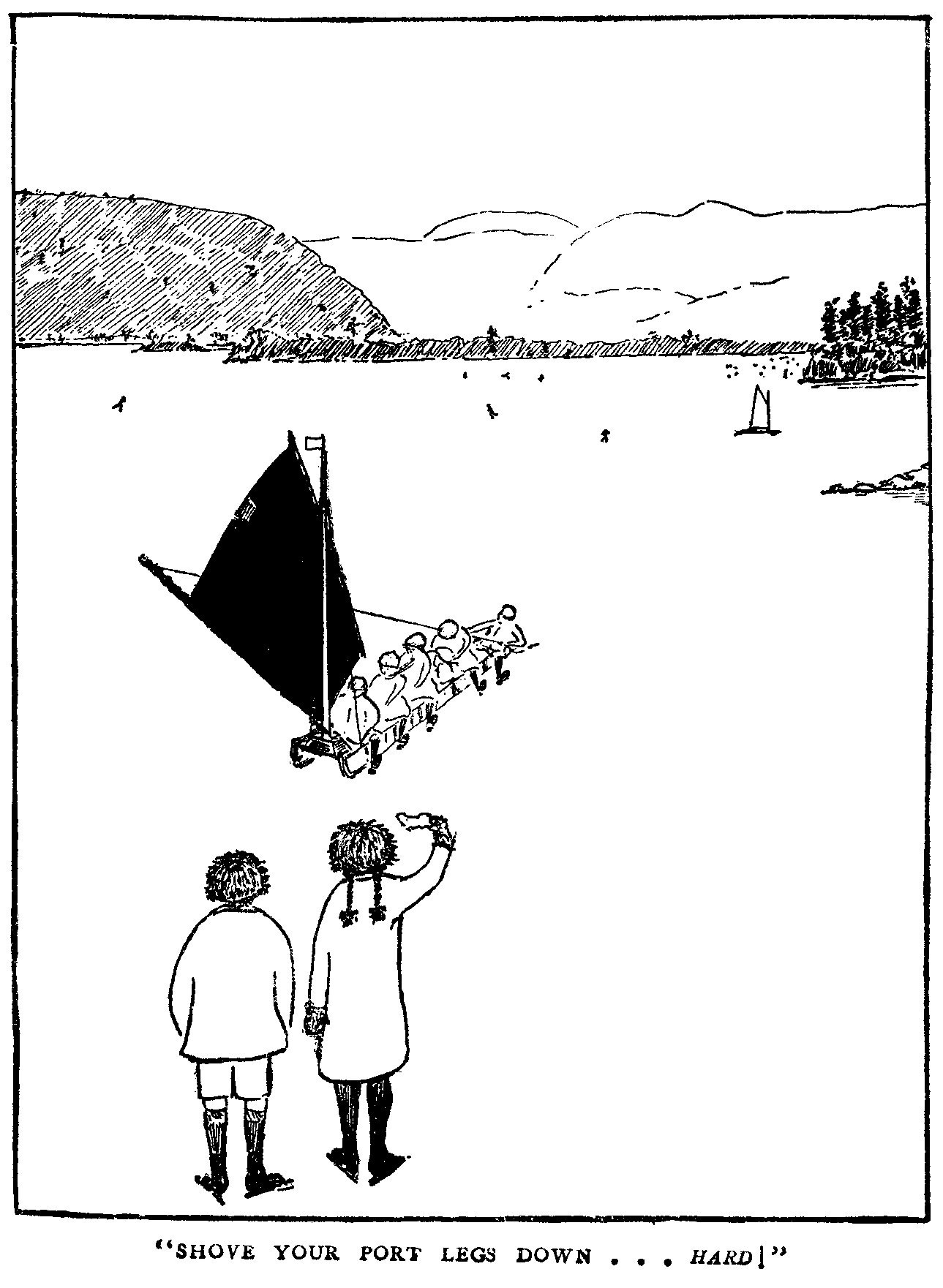

If personal memory played a large part in conjuring the polar Lakeland of Winter Holiday, Ransome also drew on other sources. He much admired the Arctic explorer and philanthropist Fridtjof Nansen and, having consulted the thick volumes of Nansen’s book Farthest North, the children in Winter Holiday add sails to their sledges.

Scenes in Ransome’s mind were also coloured by his experiences of harsh winters in Russia and the Baltic States between the years of 1913 and 1924, where he was a journalist and watched ice yachts on the Stint See in Latvia. On a visit back to Britain in February 1924 his ferry became trapped in Baltic ice (it was rescued by a German warship) and the passengers, including Ransome, played ball next to the ship. His journey should have taken four days – it took 12!

While this pot-pourri of autobiographical recollections shape Ransome’s literary landscape, Winter Holiday features the same mix of locational fact and fiction as other Swallows and Amazons titles. And apart from Swallowdale – a secret valley above the lake – few places have proved as elusive to location-seekers as Winter Holiday’s ‘North Pole’:

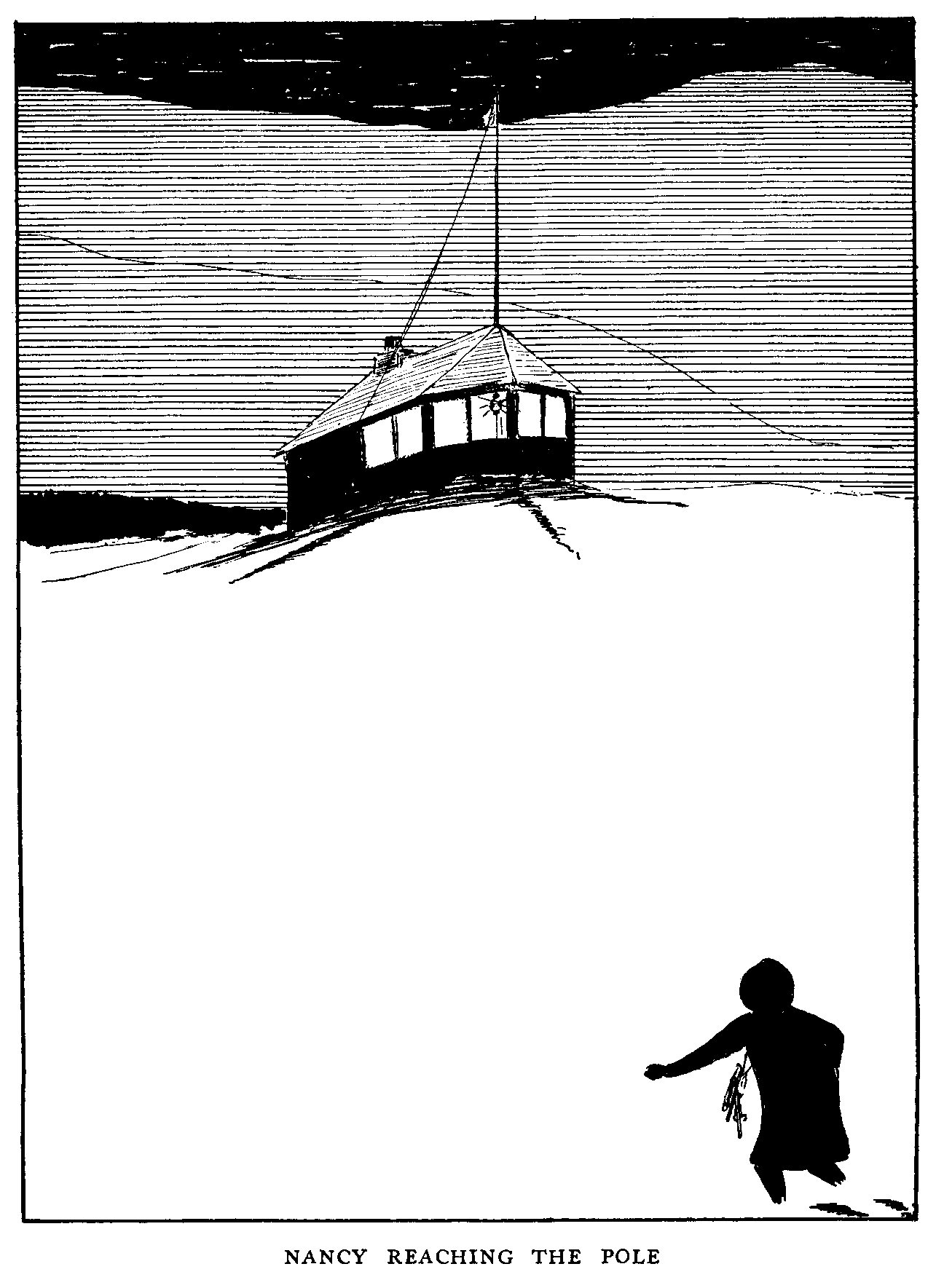

“A queer place it was that they were in. First of all, though there were wooden benches with panelled backs along the walls and round under the windows and on either side of the little fireplace, there was a six-sided seat in the middle of the room, built round the base of the flagstaff they had seen sticking up above the roof, like those seats that are sometimes built round old trees in parks.”

Where is the Pole? Suggestions have been advanced about various houses and conservatories on the edges of Windermere and Coniston Water, but none, bar one, has been convincing.

In 1993 Windermere-based sailing authority Jim Andrews investigated a recollection that, in about 1930, there had been a summer house close to the north end of Windermere in Borrans Field. Using his archaeological dowsing skills, Andrews identified post holes, a hearth, roof support post and angled windows that defined the shape of a former building on a small rise above the shore in Borrans Park. A slate plaque, set in the grass above the lake, now marks the spot.

Roger Wardale, in his 1996 book In Search of Swallows and Amazons, was intrigued by Andrews’ archaeological approach, but wrote that he was unable to find any pictures of the summerhouse – or indeed anyone who remembered it.

One plausible inspiration for a building on the shore of Borrans Park – consistent with Ransome’s description – has, however, come to light since the publication of Wardale’s book, with links to a Dodo and the MacIver family. The latter were pioneers of steamship services from Glasgow in the 1830s, and David and Samuel MacIver were associated with Samuel Cunard in founding the Cunard Line.

From 1863 David MacIver, a nephew of the original founder, and by then MP for Birkenhead and Liverpool, rented Wanlass Howe at Waterhead as a summer home (he subsequently bought the property in 1873). Launched in 1880, Dodo was the name given to a 42-foot paddle-steamer built by MacIver’s Spanish boatman in the stable yard below the house; it was called Dodo because paddle-steamers were thought by then to be extinct.

David MacIver died in 1907, after which Dodo became a houseboat, before being dismantled after the First World War. At was at this point that the mahogany and glass cabin was salvaged and adapted as a changing room near the beach below Wanlass Howe.

In 2017 a blurry photograph of indeterminate age came to light on which can just about be distinguished a small building with three windows along one side and a flagpole. The MacIver fields were purchased in 1935 to celebrate George V’s Silver Jubilee (the site is now Borrans Park), and it may be that when the land became public property, the swimming hut that had been Dodo’s cabin was removed for safety reasons.

Perhaps the search for the North Pole is no longer as dead as a Dodo, and the paddle-steamer’s cabin fits the bill? If anyone has a photograph of Dodo’s cabin in Borrans Field, this would be a fine Christmas present for Ransome fans.

Meanwhile, when it comes to winter celebrations, Nancy Blackett deserves the last word:

“…We’ve done it. We’ve all of us done it. This is miles better than anything we planned… Sailing to the Pole in a gale of wind and a snowstorm.”

To find out more about Arthur Ransome, take a look at the website of the Arthur Ransome Trust at www.arthur-ransome-trust.org.uk and to explore places that inspired his writing download a free app by seeking Swallows and Amazons in your App Store.

Illustrations and quotations are reproduced with kind permission of the Arthur Ransome Literary Estate, Penguin Random House (Winter Holiday) and the Arthur Ransome Trust (Autobiography).

‘Windermere Frost Fair’ is a 1,000 piece jigsaw new for Christmas 2024 and available to buy from Inspired by Lakeland. It is illustrated by Evelyn Sinclair of www.sinclair-illustration.co.uk.

Thanks, Jon, for your comment below. Weather events certainly punctuate and shape Arthur Ransome's story-lines. For some reason, in the long catalogue of British winters at the following link, 1895 does not feature as an extraordinary event.

https://www.netweather.tv/weather-forecasts/uk/winter/winter-history

Excellent. The conclusion about MacIver and Dodo as the source of AR's North Pole is new to me.

It's also striking that in his next book, 'Pigeon Post', we see a summer of heat and drought. Again everything is grounded in natural conditions, with the scarcity of water and the risk of fire being major plot-drivers.

As a sailor and angler, and a pretty decent amateur naturalist (as reflected in the character of Dick in the stories), Ransome was well in tune with the natural world. It's intriguing to speculate what he would have made of our current preoccupations with climate change, biodiversity loss, and so on.