Hefted magazine: Spring 2025

Despatches from Cumbria and the Lake District, from the team at Countrystride and Inspired by Lakeland

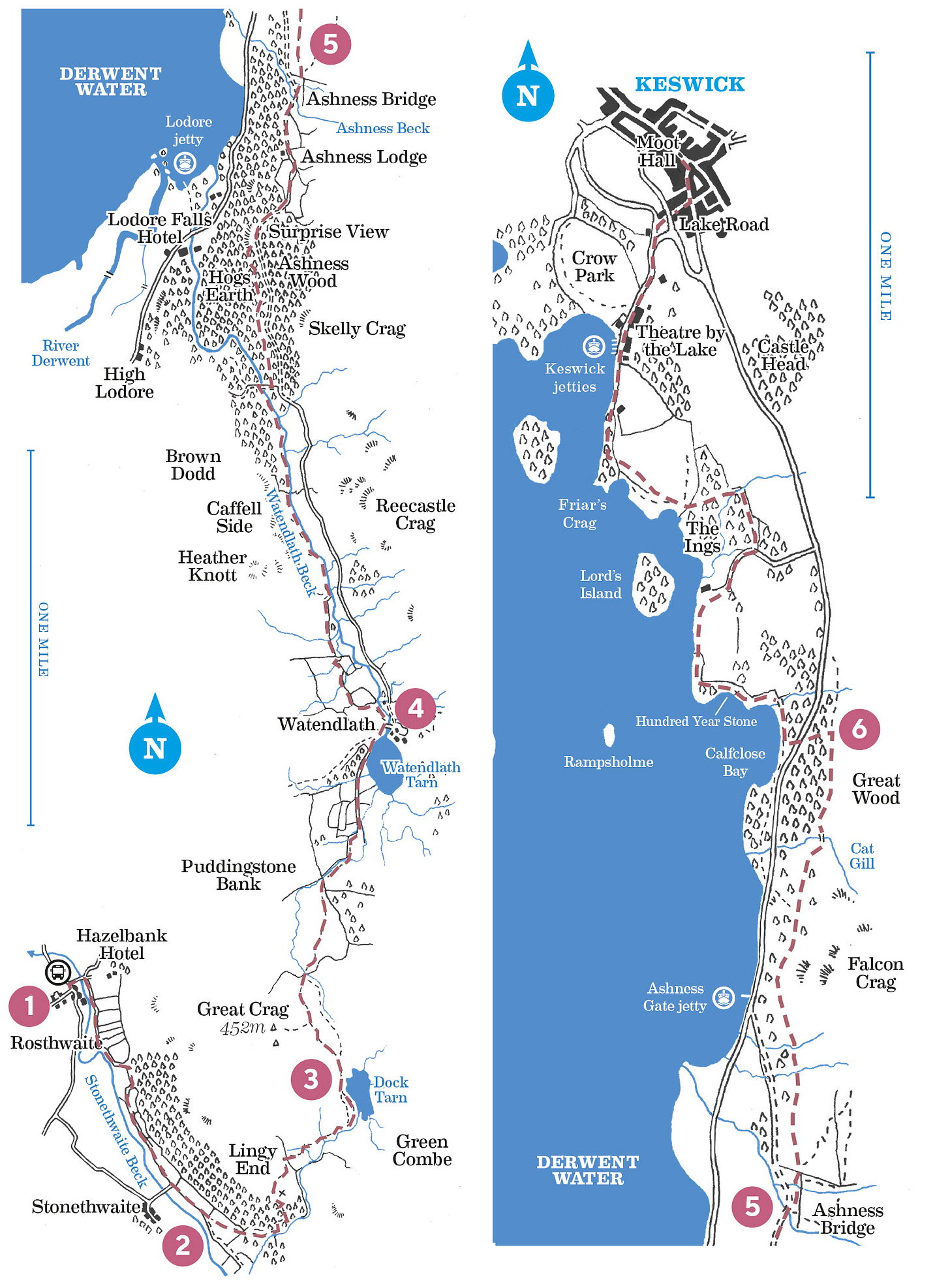

In our Easter edition, Dave Felton profiles his five favourite Lakeland river walks; Mark Richards visits Dock Tarn, Surprise View and Watendlath in his Walk of the Month; while Alan Cleaver has a nature-filled Spring in his step.

‘The Pimp’*: Five of the best…

Lake District river walks

As picked by Dave Felton.

#1. River Derwent: from Sprinkling Tarn to Derwent Water – 8.8 miles

There is something satisfying about following a river from its source to the sea (witness the popularity of long distance trails like the Thames Path and Severn Way). And while a multi-day trek from the River Derwent’s source above Sprinkling Tarn to its Irish Sea outflow at Workington would make a grand adventure, the stretch that offers most scenic variety is surely the 9-mile walk between Great End and Derwent Water.

From the strategically important walkers’ crossways below Esk Hause, a steady pitched descent follows the nascent river as it tumbles down its first rocky miles, first as Ruddy Gill, then Grains Gill towards Stockley Bridge, the one-time pack-pony bridge, now trod by a thousand-and-more pairs of boots a day, many bound for Scafell Pike.

Levelling in the valley bottom at Seathwaite, the river drifts below remnants of Atlantic rainforest, where mosses, lichens and liverworts create a living second skin on boulders, oaks (the river’s Celtic name derives from them) and the valley’s near-unique hillside of pollarded ash. Joining Hause Gill at Seatoller, the Derwent widens to arc through the meadows of Borrowdale, soon tracked by the Cumbria Way for one of the loveliest wooded walks in Lakeland, that threads below Castle Crag and through the Jaws of Borrowdale.

Exiting the cragged confines, the valley opens and the Derwent slows in drifting meanders to pass beneath the twin-arched road bridge at Grange, soon to enter Derwent Water, distant Skiddaw rising about the tan rushes of Manesty.

#2. River Esk: from St Catherine’s Church to Doctor Bridge (and back) – 4.5 miles (including Stanley Force)

Is there a lovelier stretch of river walking in a lovelier valley than the perfect there-and-back from St Catherine’s Church in Boot to Doctor Bridge?

Such a walk might begin at Dalegarth Station, terminus of La’al Ratty (though in days past, two spurs of the line continued up-dale, one serving the iron mines of Boot; the other bearing southeast to Underbank). From here, walled meadow ways lead to St Catherine’s Church, where strike left, upstream, initially on the former trackbed of the old mineral line, soon to find a riverside terrace flanked by woodland, with furtive glimpses of the Esk in its pebble and bedrock-smooth surrounds.

Doctor Bridge’s former life is glimpsed from below. Note on its left edge the narrower stonework of the original 17th-century packhorse bridge. The name derives from 1734, when the structure was widened so that surgeon Edward Tyson could drive his pony and trap over it. The path now traces the south bank home, past an innominate pine-fringed tarn where red squirrels play, and – if time and inclination allow – to the viewing platform above Stanley Force, a Picturesque attraction since the late Georgian era.

My only plea? That someone with more skill and strength than me might re-set the St Catherine’s stepping stones.

#3. Aira Beck: from Brown Hills to Ullswater – 4.5 miles

A ‘source to (kind of) sea’ walk, the 4.5-mile wander from the common below Brown Hills to Ullswater is one for the connoisseur, descending past sheep pasture, tended meadows, lush woodlands and, as a final-mile treat, Lakeland’s most visited waterfall.

Dowthwaitehead – a half-mile below Little Aira Beck’s soggy source – is a perennial enigma. It’s there on Christopher’s Saxton map of 1576, though it must at that time have been – as it now is – a backwater of backwaters. Wainwright, when he came this way in the 1950s, noted the hamlet’s “air of neglect”. “Five families used to live here; now there are two only.” In the following decades its population fell further, until the farm – along with 292 acres of the valley – was placed on the market for £2 million in 2021. Subsequently acquired by the Pinfolds, the farm buildings and valley walls have undergone significant repair, as this backwater valley – for generations a stronghold of the Weirs – begins life anew.

When Lakes crowds swell, this cul-de-sac dale is a refuge. And the downstream wildlife oasis of Lucy’s Wood – planted in the late ‘90s as a living memorial to 17-year-old Lucy Farncombe – puts people into this loved landscape. A swift pint, in whatever weather, at the Royal Hotel, Dockray, is prelude to the last and loveliest of miles, downstream to Aira Force. You are unlikely, of course, to have these charmed banks to yourself. But thus it has been since the 1780s, when the Duke of Norfolk first began landscaping the verdant canyon in the midst of his hunting estate. 250 years later, those honeypot falls still wow, as the water proceeds downstream through the arboretum to form the gravel delta (Old Norse, eyrr) into Ullswater, which gifts the river its name.

#4. River Duddon: from Cockley Beck to Seathwaite – 4.5 miles

Journalist John Pepper – who lived for a while at Cockley Beck – takes a literary tour downstream from his seasonal home in the neglected 1984 classic Cockley Beck: A Celebration of Lakeland in Winter, descending the River Duddon from its headwaters near the Three Shire Stone to Kirkby and Askham in Furness.

For those with gentler ambitions, the 4.5-mile riverside walk from Pepper’s former winter retreat to Seathwaite is adventure enough. Heading southwest, initially ruler-straight along the Roman Road that once linked Ravenglass with Ambleside, it is energising to note the nature revolution unfolding in the surrounding hills. Across a site of 630 acres, native broadleaves are replacing conifers in the ongoing restoration of Hardknott Forest, while National Trust tenants are re-wetting bogs, nurturing heathland and adding trees into pastures as part of Lakeland’s (whisper it) least noisy landscape-scale recovery scheme.

Downstream of Froth Pot (where a dip in the turquoise waters is semi-obligatory, if invigorating, even in the height of summer), the going gets steadily rougher; the traverse below Swinsty How and Long Crag offering the kind of wilderness-style riverside tramp (waist-high shrubs; thigh-deep bogs) that is rare in Lakeland. Past the stepping stones, the riverside way crosses a lateral path aimed for an even rarer patch of beech woodland – a blaze of colour in both spring and autumn. A final-furlong adventure passes through Dunnerdale’s equivalent of the Jaws of Borrowdale, as crags narrow between Wallowbarrow Crag and Pen. End the mini-adventure with a pint at the Newfield Inn, with its unique banded-slate flag floor.

#5. Cald Beck – from Hesket Newmarket to Caldbeck – 4 miles, there and back

Some mild cheating is needed on this fifth walk, the first mile from Hesket Newmarket to the Cald Beck actually along the River Caldew (‘Cald’ is Old Norse for ‘cold’), making this a twin river walk. But this mile is not only needed to form a satisfying circuit (via Nether Row), it is also the highlight of the route – through riverside woodland studded Springtime blue with bluebells and enveloped by the smell of ramsons.

Arriving at the watersmeet of both rivers, where the flow is confined by limestone banks, the path exits the National Park and climbs to join the Cumbria Way, at this point – for south–north journeyers – in the closing miles of the trek to Carlisle. The path swings west now along a high-level terrace through long-worked woodlands before dipping down to Caldbeck, where the Watermill Café provides riverside refreshment.

Time slows in retiring Caldbeck, opening hours to explore the churchyard of St Kentigern’s (find the graves of huntsman John Peel, and Mary Robinson, the ‘maid of Buttermere’, who found peace here after escaping Buttermere and bigamy), the village green and The Howk, with its waterfall and stately old bobbin mill. From here, either backtrack for more riverside loveliness, or strike south, still on the Cumbria Way to Nether Row, thence northeast to Hesket.

Dave publishes a range of award-winning Lake District books as Inspired by Lakeland.

* For the avoidance of doubt, ‘pimp’ is number five in Cumbrian dialect.

Striding out: Mark Richards’ walk of the month

A Watendlath wander – 9.25 miles, 1,660ft ascent, 5 hours

To celebrate the arrival of The Keswick Walking Companion, published by Countrystride this month, here is a secret hanging valley walk. Dock Tarn, Surprise View and the valley of Watendlath are scenic highlights of this 9.25-mile outing, strung together by a succession of ageless footpaths, oak-wood ways and waterside trails. In summer, the wildflowers are a joy; in autumn you’ll be walking among trees of gold.

Board the 77/77A Honister Rambler or 78 Borrowdale Bus in Keswick (Booths) and alight at Rosthwaite.

From the bus stop, leave the valley road along the fenced access lane (waymarked ‘Stonethwaite, Watendlath’) that leads left over Stonethwaite Beck to Hazel Bank Hotel. Coming to the entrance of the hotel, bear right on the tree-shaded confined path (‘Stonethwaite 1 mile’). Soon terracing above the river, this becomes an enchanting, intermittently walled lane with occasional gates that threads between meadows for just shy of a mile. Proceeding up-dale, with woods above left and a wall close-right, the rising bastion of Eagle Crag becomes ever more dominant in the valley ahead; the river, right, is also worth noting – new gravel beds are the result of re-profiling work on the previously artificially-channelled banks. Ignore the gated lane to Stonethwaite, right, and keep ahead via the facing gate, still with the wall close-right.Soon after an oval sheepfold and subsequent stone steps, break off the main track along a grassy path that strikes diagonally up the bank, left, to enter oak woodland at a wall-stile. The path, now guided by cairns through a hand-gate, begins a 700ft stepped ascent of the hillside. It’s a stiff climb, but height is gained without complaints in this loveliest of hanging woods.

Two things to consider during the climb: firstly, before early settlers and later generations of landowners began clearing the original ‘great wood’ for fuel, timber and grazing lands, woods like these would have flanked the majority of Lakeland fellsides. Second, lovely as it is, there is scant understorey below the oak canopy – little in the way of younger trees to ensure succession; a sign of generational overgrazing by sheep and deer. Later in the walk we pass through the far healthier Hogs Earth wood.

Tight zig-zags carry the path above the tree line and past a roofless building – a former peat hit – on Lingy End, from where superb views open south to where the valleys of Greenup Gill and Langstrath converge, Eagle and Sergeant’s Crags standing watch above.

Cresting the brow, the onwards path weaves through the first hints of heather to ford a feeder gill of Willygrass Beck and cross a wall-gap stile. Ignoring minor branching trods, keep with the stony main way as it follows the beck upstream for a first glance of Dock Tarn, named after the lilies that have flowered here for centuries. At an obvious path junction before the tarn, ignore the main way that bears uphill and left through the heather, and instead drop down ahead and follow the left-hand (west) shoreline of the tarn.Leaving the tarn behind, the path meanders over marshy terrain studded with ice-scoured bedrock. At a vague T-junction, keep right with the main way as it descends by neatly pitched steps, with an early glimpse of Watendlath Tarn backed by High Seat. Pass through the kissing-gate, cross the beck, then skirt right above the bog myrtle marsh on a part-paved path that avoids the worst of the wet.

The path comes by an old fold, then drops to a wall junction. Bear right through the gate/kissing-gate and descend alongside the wall and beck, left. After a ford, the path becomes a track, now crossing the in-bye pastures of the hanging valley. It runs on over another ford to enter the western walled ‘outgang’ of the valley at a wall-stile/gate.The Norse-derived term ‘outgang’ – literally ‘going out’ – refers to a walled lane that gives livestock passage between the enclosed in-bye meadows near farms and the open common above. Livestock can be driven down outgangs without fear of escape. Descending the Watendlath outgang, note the wall, left, which is the ‘ring garth’ – the original wall that marked the upper limit of enclosure from the earliest periods of agricultural settlement. It dates from the 13th century.

The lane descends via another ford and two gates to come by the shores of fell-cradled Watendlath Tarn. A rock lip forms the final approach to the tarn outflow’s scenic footbridge, where spot an engraved pebble inserted into the cobbled floor by King Charles III in 1995 following its re-build. Caffell House, on the far side of the bridge, has a seasonal tearoom.

Watendlath Tarn is stocked with trout, and fly fishers can frequently be spotted casting from the shallow shores – netting near the outflow helps to control the movement of fish. The place-name Watendlath refers precisely to the situation of the cluster of farmsteads and translates as ‘water end laithe (barn)’.

Watendlath plays an unlikely role in Lakeland literature, this shy upland hamlet an important location in Hugh Walpole’s Herries Chronicles. Specifically, Fold Head Farm is almost certainly the fictional home of Judith Paris. The Herries series comprises four novels that tell the story of a Cumberland family between 1730 and 1930. Although Walpole’s once best-selling titles have fallen out of fashion, the Chronicles are worth seeking out for evocations of Lakeland life past (for more, seek out Countrystride #95).Our walk does not cross the bridge. Instead, it holds to the west side of the Watendlath Beck valley beneath Heather Knott/Caffell Side. So bear left through the gate immediately before the bridge (signposted ‘High Lodore & Ashness’) and follow the river down early bedrock steps (note the hydroelectric infrastructure, right, which powers buildings in the valley – we visited it with Roy Henderson in Countrystride #99). The path is then steered left and uphill by walls, before bending right through a hand-gate. Proceed with the wall, negotiating a series of footbridges and gates before descending onto the level ‘strath’ valley floor down a slate-flagged stairwell. The next 0.75 miles is charm indeed as the path accompanies the beck’s left bank over wildflower-rich watermeadows and along rocky riverside shelves. Picnic spots abound.

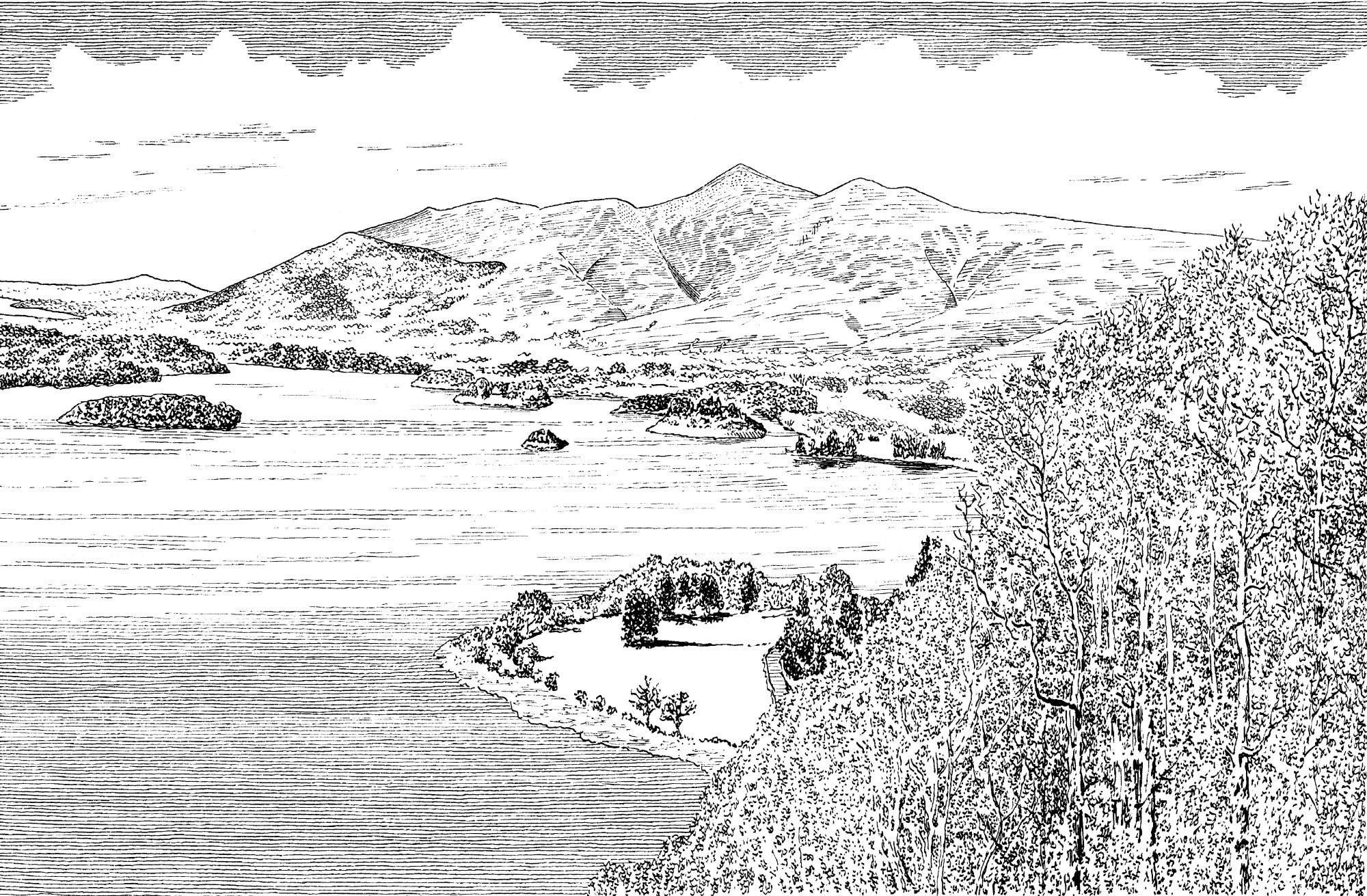

After a pair of footbridges, the path enters woodland pasture. Emerging at a T-junction alongside a stone-piered footbridge, bear right over the bridge then left through the subsequent hand-gate. The easy track rises steadily through Hogs Earth – a far healthier woodland than those of earlier, with a mix of older trees, verdant understorey and saplings. 30 yards before joining the unenclosed valley road, leave the track, left, on a minor off-shoot path that follows the road at a distance, wending through the woods (taking care of the scarp edge, left) to visit Surprise View (pictured above), with its famous outlook over Derwent Water.

Proceed downhill, now on the road, to pass Ashness Lodge – a modernist take on vernacular Lakeland, replete with a re-imagined Westmorland chimney. The road leads down to the bridge crossing of Ashness Beck, another famous scene enjoyed by a steady flow of visitors who direct their cameras to capture the graceful backdrop of Skiddaw.20 yards after crossing Ashness Bridge step up, right, onto a bracken-flanked terrace path (signposted ‘Great Wood 55 mins’), that soon fords a gill, and climbs rock steps to pass through a hand-gate. Ignoring the waymarked right-hand branch to ‘Walla Crag’, the subsequent path (‘Great Wood’) undulates for just over half-a-mile through brackens and briars. There are rocky moments and a couple of further gill crossings as the path traverses beneath the rising cliffs of Falcon Crag.

As the path declines after the crag, keep watch for a narrow trod that drops away, left, past some yew-shielding tree cages. The path descends by birches and a cluster of huge boulders to step onto the busy Borrowdale Road at a parking lay-by.Cross the road and bear right for a few steps, where a rocky, rooty passage switches back left down the bank onto the shore of Derwent Water (when waters are high, continue along the road until you are able to make a passage, left, to join the lake-side walk).

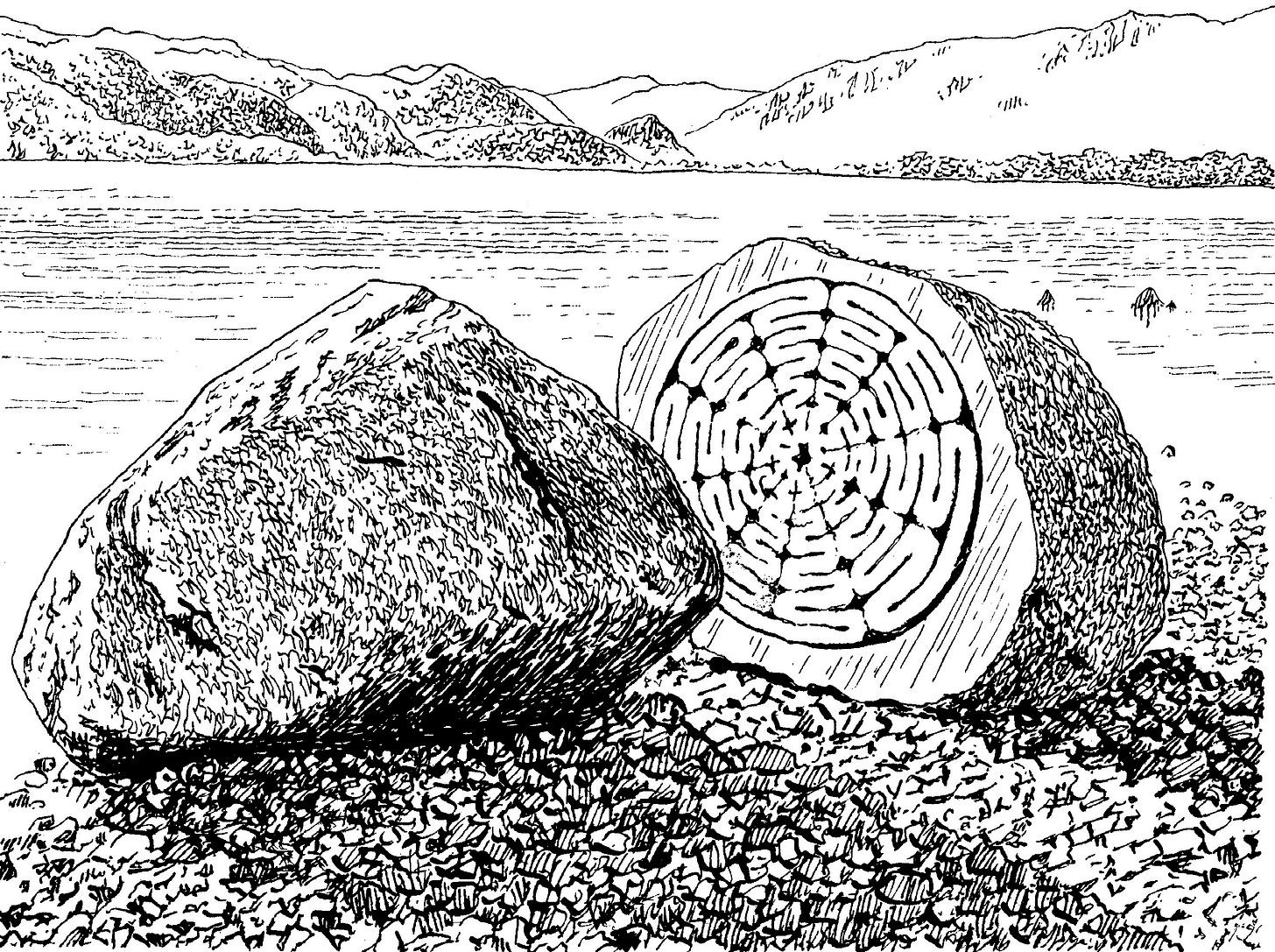

Once beside the lapping waters, bear right along the shoreline, soon crossing a plank bridge, where ramsons add a pungent aroma to the breeze in spring. The woodland way rises to a cobble-platformed bench, then drops to another beach. Keep left along the shore past tree roots exposed by the agitation of water. Cross a plank bridge over the inflowing gill, then swing left around Calfclose Bay to inspect (if not submerged) the split ‘Hundred Year Stone’ artwork, sculpted by Peter Randall-Page in 1995 and installed to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the National Trust (it is located on the beach, left, immediately before the path enters a yew grove).

Come onto Broomhill Point with its copse of aged yews, the path now leading on, right, through a hand-gate. The path leads on by a hand-gate, where note, right, the faint remains of ridge and furrow in the pasture – a possible reminder of ambitious, if often short-lived, cultivation made expedient by the food shortages of the 18th century caused by the Napoleonic Wars. The track trends right of Stable Hills cottage, then bears left over a cattle-grid into a hedge-lined access lane. Where the lane forks, bear left again (‘Friars Crag 0.5 mile, Keswick 1.25 miles’) to cross the Ings wetlands on boardwalks and raised paths.

When the second boardwalk ends, go through the hand-gate and stroll left around the bay, Cat Bells now resplendent across the lake. A second hand-gate opens onto pine-crowned Friar’s Crag, where rustic fencing swings the path sharp left to arrive at the famous viewpoint. The bench at the promontory is one of Lakeland’s most enjoyed, where people gaze longingly towards the Jaws of Borrowdale and a majesty all around. Inset from the water is a stone monument erected in memory of John Ruskin (Countrystride #15).

Keeping the lake close left, proceed north along the wide oak-lined track. The ensuing lane leads through tourist hordes above the launch landing stages. Now re-entering Keswick, pass Theatre by the Lake, right, then continue downhill with the walkway as it enters Hope Park. Arriving at a crossways by the park café, bear right (‘Town Centre’) beneath the underpass, then right up Lake Road. At George Fisher swing left and follow Lake Road back to the Moot Hall.

Mark is author of five Countrystride Walking Companions, each featuring dozens of walks, line illustrations and insights into local landscape, history and heritage.

The Keswick Walking Companion features 16 ambles, rambles and scrambles in and around Keswick. It is available now from Inspired by Lakeland.

Cumbriana: A Spring in his step

A column of curiosities, with Alan Cleaver

There are countless books on Cumbria and its natural, local or social history that have been neglected with the passage of time. One of them is James Robinson’s 1878 title, A Country Lane: Its Flora and Fauna.

It is thanks to the diligent efforts of Sue Shiels and the Burneside Heritage Group that this minor classic continues to attract attention, and Sue’s 2013 reprint is still available.

James Robinson – born at Hawkshead in 1824 – worked as cashier at the Cropper Paper Mill in Burneside. Every day he walked from his home in the village of Bowston to the mill down Back Lane, on the north side of the River Kent, and he kept a detailed record of the flora and fauna he passed as he walked.

The preface to A Country Lane reads as follows:

“By dint of frequent perambulation, at all times of the year and at all hours of the day, I have become familiar with the natural garniture of the lane — its flora and its fauna; and I venture to think that a short description of some of the things which may be seen and heard in this peaceful by-way (a representative of many more), may possess an interest to those who love to regard nature even in her lowliest aspect, and who, in their quiet walks, can heartily join in the sentiment of Linnseus, and ‘thank God for the green earth’.”

He wasn't wrong. The 28-page booklet details over 50 plants and 30 birds and animals that he encountered on his walks. Not only is it a charming account to read, it is also valuable for naturalists who can compare the state of Back Lane today with how it appeared to Mr Robinson more than 150 years ago, before the era of modern farming and motorised transport.

Spring opens gently in Robinson’s exquisite prose:

“The first of Flora's forerunners to open its tiny petals to the soft breath of early spring, and the fitful gleams of a February sun, is the Vernal Whitlow Grass (Draba xerna), which appears on a dry sunny part of the slope. So small is this plant, that but for its growing in patches, it would often remain unobserved, especially in wet or cloudy weather, when its small pearly flowers close up. Next to the snowdrop it is perhaps the first flower of spring, and, on this account, as well as for beauties of its own, has a particular claim on our notice.

Closely following in the train of this humble pioneer comes the common Primrose (Primula vulgaris), with its wrinkled leaves, the known and loved of all. As its salver-shaped blossoms (which have given their name to a colour) lighten up the grassy slopes of field and lane, bright hopes are awakened in the breasts of old and young, for they are a token and a pledge that sullen winter is at last vanquished, and that victorious spring — soon to be crowned with garlands — has taken possession of the earth.

You can still walk Back Lane today. It is a single-track road, so you need to take care of the occasional car passing along it.

There is, however, every chance you will see or hear the robins, blue tits, coal tits, wrens, crested lapwings or whitethroats that kept Mr Robinson company on his amble along the lane in the 19th century.

When I last walked the lane, it was a wren that chose to keep me company. This tiny bird is usually heard before it is seen, trilling away. It crams an impossible number of notes into a few seconds – a song likened to the firing of a gentle machine gun. It is a bird that thankfully still thrives; in Spring it is estimated there may be more wrens than humans living in Britain.

In folklore, the wren is known as the King of the Birds. Legend tells how a competition was held by the birds to decide on a king; the crown earned by the bird that flew highest. The eagle soared to a great altitude, but every time it reached its zenith, a wren popped out from the feathers on its back and jumped a couple of inches higher. So it was that the wren won the royal crown.

Of the wren, Robinson had this to say:

“A bold and valorous bird is the Wren. To some of his deeds of daring I have been a witness. Often is he seen perched on the highest twig in the hedge, with bill extended to the utmost, pouring out his shrill treble. That such a volume of sound should proceed from such a tiny object is wonderful. Undisturbed by noisy traffic or juvenile foes the birds in my lane are comparatively tame, and apparently take little heed of my presence.”

If you park in Bowston and walk along the lane to Burneside, you can, if you prefer walk back to Bowston via the Dales Way along the banks of the River Kent.

Mr Robinson's original book is available online at https://archive.org/details/countrylaneitsfl00robiiala.

The reprinted fascimile can be acquired from various sources, including summerfieldbooks.com/product/a-country-lane-revisited/

Follow Alan on Twitter/X at x.com/thelonningsguy