Hefted newsletter #2: August 2024

Dispatches from Cumbria and the Lake District, from the team at Countrystride and Inspired by Lakeland

Welcome to the second edition of Hefted, a monthly newsletter from Mark Richards and Dave Felton at Countrystride featuring a range of bite-sized news, views and long reads centred on the landscapes, people and heritage of Cumbria and the Lakes.

This month, our Long Read rewinds time to the golden age of steam in the mid-19th century and the definitive map of Cumbrian railways at their zenith; Mark takes a route less trod onto Helvellyn; Alan Cleaver explores one of Lakeland’s most beautiful lonnings; and our Postcard from the Past features the original Professor of Adventure, Millican Dalton.

The gather: Pick of the Cumbrian headlines

Hundreds of fell- and trail-runners travelled to Wasdale in July to form a ‘guard of honour’ ahead of the cortege of Joss Naylor MBE as it made its way to St Olaf’s Church at the head of the valley. Joss’ family had requested “attendees walk in front of the cortege to lead him home”. More from the BBC.

The Lake District National Park Authority has named its new CEO as Gavin Capstick. Tebay-born Capstick joined the Authority in 2018 and was appointed Director of visitor services and resources in 2022. In a statement issued by the Park he outlined his three priorities: supporting nature recovery and agricultural transition; promoting ‘low impact visiting’; and helping people access and learn about the National Park and World Heritage designation. Mr Capstick will take the baton from outgoing chief exec Richard Leafe – who has led the Park for 17 years – in October. More from the National Park Authority.

Social media influencers are having a “massive impact” on the Lake District – both good and bad. National Park Authority board member Peter Walter reported that the Park’s visitor management team have a never-ending job keeping up with what influencers are profiling and knowing where to send enforcement officers. More from The Keswick Reminder.

Is 2024 turning into a record year for Lake District mountain rescue? With year-on-year call-outs up by 5 per cent and fatalities soaring by 100 per cent, Hefted delves into the stats and asks whether 2024 is set to be a record year for the service. More from Hefted.

An iconic 1920s cinema has shown its final film. Charles Morris, manager of The Royalty in Bowness, which opened in 1927 and houses a Wurlitzer organ, will not be renewing his lease on the building with Westmorland and Furness Council. “The level of admissions currently is about a quarter of what it was in our heyday,” said Morris. “The Royalty can still excel itself on a wet afternoon, but there are not actually as many of these as the area’s reputation would suggest...” More on Facebook.

…Meanwhile, the north Lakes is having a bumper cinematic year. After crews were seen filming for a new Netflix Harlan Coben thriller last month, in recent weeks production vehicles at Keswick Rugby Club and lay-by closures around Thirlmere and Catbells have prompted speculation that filming is underway for the fourth instalment of Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary starring Renée Zellweger. More from The Keswick Reminder.

The Lakeland Book of the Year title has been awarded to Grasmere-based Polly Atkin for Some of Us Just Fall – “a book about living better with illness”. Other winners at the 2024 event included ex-Penrith and The Border MP Rory Stewart for his best-selling political memoir Politics on the Edge and two titles published by Countrystride’s very own Dave Felton, A Literary Walking Tour of Carlisle by Penny Bradshaw and Sketching A Year in Lakeland by Liz Wakelin.

1,000 cannabis plants have been discovered during a raid in Whitehaven. Police arrested two men after the town centre operation. More from the BBC.

A new 2MW solar farm, being built by Westmorland and Furness Council, will be operational later this year. The £2.8m facility, located on a 29-acre site at Sandscale Park, Barrow, will provide enough electricity to power the council’s leisure centres. More from the BBC.

In other renewables news, Project Collette, the ambitious plan to build a major new 1.2GW community wind farm off the Cumbrian coast – large enough to power around one million homes a year – is undergoing a series of engagement events. More about the project here.

And finally… a rare 1958 nuclear bunker near Dent Station has been sold at auction. The ROC Nuclear Bunker, which sold for £48.000 – more than double the guide price of £15,000-£20,000 – was described as “secure, dry and in its original condition” by agents SDL. “It was designed to provide protective accommodation for three observers to survive a nuclear attack. They were provided with enough food and water for 14 days and had a land line and radio communications available to them.” More from SDL Auctions.

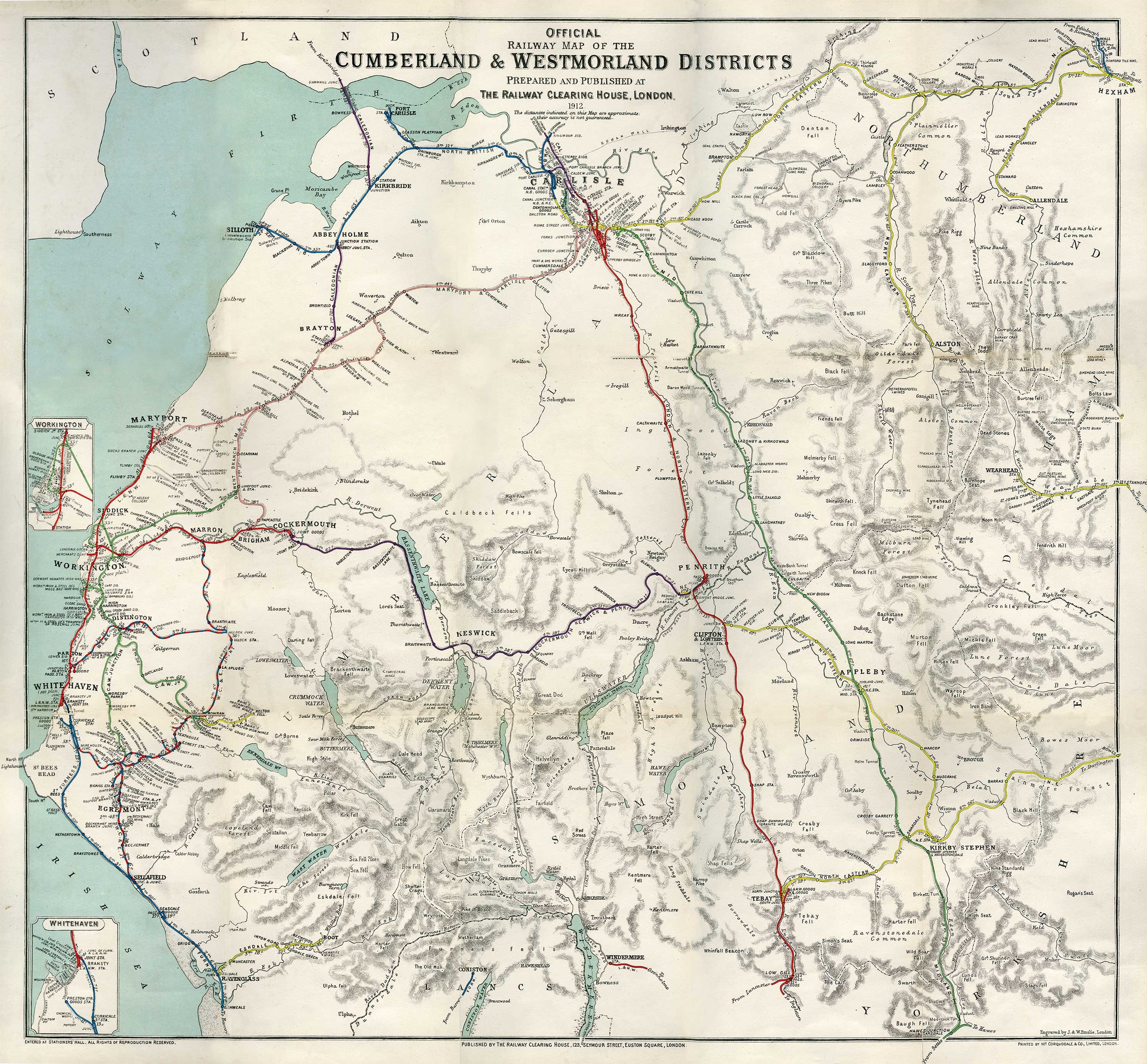

Long read: Maps of Cumbria – ‘Official Railway Map of the Cumberland & Westmorland Districts, prepared and published by The Railway Clearing House, London’

This official map of the railway network at its zenith shines a light on the industrial age

Words by William D. Shannon and David Felton

By the mid-19th century, the golden age of steam had arrived. Dozens of companies were operating their own stretches of railway, while wealthy industrialists, motivated to find faster ways to transport raw materials and goods to market, employed surveyors to map new lines before Parliamentary powers were sought to enable compulsory land purchase.

The first railway to reach Cumbria was the Newcastle and Carlisle line in 1838, constructed so that Newcastle could ship its iron via Port Carlisle to the west coast ports of Liverpool and Bristol. The line was surveyed by the pre-eminent rail engineer of his age, George Stephenson, and with Stephenson in the area – coupled with a growing recognition among Cumberland landowners that rail would revolutionise their coal businesses – agents of the Senhouse family (of Maryport), the Curwen family (of Workington) and the Lowther family (of Whitehaven) employed the ‘father of railways’ to survey lines extending west from Carlisle, then down the Cumberland coast. In subsequent years, a flurry of building activity added three new lines to the map: the Maryport and Carlisle Railway in 1840, the Cockermouth and Workington Railway in 1847 and the Whitehaven Junction Railway in 1850.

The best route between Lancaster and Carlisle was argued over for decades. Should it go via Longsleddale, the Ribble Valley, or even – as George Stephenson’s son Robert argued – along the Cumbrian coast as the Grand Caledonian Junction Railway? In the end the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway (later the London and North Western, now the West Coast Main Line) was routed over Shap and opened in 1846, followed in 1857 by The Furness Railway. Between 1876 and 1923 half-a-dozen different companies were operating out of Carlisle’s sprawling Citadel Station.

The proliferation of privately owned railway companies created myriad logistical challenges, not least over how revenue was apportioned if a train needed to use more than one line. If a passenger booked a train from A to B, and if the stations and lines between them were operated by the same company, then splitting the cost of a ticket was easy: the single rail company received the lot. But when different companies were involved – which they frequently were – then a central body was needed to work out how long a passenger or goods train spent on each section of line, and how to divide the ticket price fairly, usually on a pro rata mileage basis. That body was the Railway Clearing House (RCH). Set up in 1842 at offices near Euston Station, it was initially a membership organisation owned by railway companies to lay down industry standards. It also adjudicated when problems arose between companies.

The scale of the Clearing House’s challenge can be seen on the map of Cumberland and Westmorland above, one of a large number of such maps, from county level down to plans of individual junctions made by the RCH to aid in its allocation of revenues.

The Official Railway Map of the Cumberland & Westmorland Districts made in 1912 (the maps were regularly reprinted as the landscape of rail companies changed) shows the main London and North Western Railway Company (‘L. & N. W.’) line (in red) over Shap and through Penrith to Carlisle, and the branch line to Windermere via Oxenholme. In the east, arriving via Settle and Appleby, is the Midland Railway Company’s line to Carlisle (green). At Penrith, the now-lost Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith line meets the L. & N. W. (a short section of the former survives as the Keswick–Threlkeld ‘railway trail’; further west its trackbed was used as the route of the A66 alongside Bassenthwaite Lake).

It is on the mineral-rich west coast of Cumberland that most railway activity is seen. The main line is the Furness Railway to Whitehaven, opened piecemeal between 1847 and 1850 with the support of the 2nd Earl of Lonsdale. From Sellafield northwards the line – now the Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railway (‘W. C. & E.’) – takes a circuitous route (with numerous branch lines) via Egremont to a junction named Marron by Bridgefoot near Cockermouth. The W. C. & E. was a mineral line opened in 1855 to transport haematite from workings around Cleator Moor, Florence mine near Egremont, and the mines of Beckermet. Diverting from this line is the Cleator and Workington Junction Railway (‘C. & W. Jn.’), opened in 1879. It, too, was associated with the iron mines of the district.

The Maryport & Carlisle line was initially concerned with moving coal from the collieries of the West Cumbria coalfield to Maryport, from where it was shipped to Ireland. A branch line of the Maryport and Carlisle, named as the Derwent Branch, extends to Cockermouth from Bullgill Junction.

Further north, the Caledonian line (initially the Solway Junction Railway – built to move haematite from West Cumbria to the furnaces of Lanarkshire, opened in 1869) is seen leaving Brayton for Abbey Holme and Kirkbride before swinging north and crossing Bowness Moss then the Solway on its famous 1.2 mile-long railway viaduct. This whole project, mainly conceived so that trains could avoid the bottleneck of Carlisle (and save 20 minutes from the journey north) was – even by the standards of the time – a remarkable feat of engineering, not least in crossing the raised mires of the Moss, where some 90,000 wooden faggots were laid to ‘float’ the line on the bog. The viaduct was badly damaged by ice flowing down the Solway in 1875 and again in 1881. It subsequently closed to passengers in 1914 and freight in 1921. It was demolished 13 years later, its iron sold as scrap to Japan – though traces of the viaduct are still visible from Bowness.

The last notable line, the North British, linked Carlisle with Port Carlisle before dropping west to Silloth (the town developed as a new port for Carlisle when Port Carlisle started to silt up). Both were taken over by the Edinburgh-based North British Railway (‘N. B.’) in 1862.

The fate of the Clearing House, with its Herculean logistical task, was intrinsically linked with the fortune of the railways. As the number of rail companies declined – partly through bankruptcies, mainly through consolidation – its role was diminished. By the time of the Transport Act 1947 only a handful of companies remained, each of which was nationalised in 1948. Dissolved in 1955, the Clearing House continued to operate as part of the British Transport Commission until 1963, when the British Railways Board took over its remaining functions.

The map

This small extract, of the area around Distington, Cleator Moor and Egremont, shows a handful of the many branch lines and sidings that served the mines and quarries of the area that provided the complex tangle of lines their raison d‘être.

The Cleator & Workington Junction Railway (‘C. & W. Junction’ on the map) – the so-called ‘track of the ironmasters’ – was built to overcome the west coast stranglehold maintained in the 1860s and 70s by the Furness Railway and the Whitehaven, Cleator and Egremont Railway (‘W. C. & E.’). When the former company upped its freight charges in 1873, local businessmen responded by proposing their own railway, running parallel to the west coast line and just a few miles inland. Despite fierce opposition from the W. C. & E., the Cleator & Workington Junction Railway was given Royal Assent in 1876.

Mines and mining companies named on the map include: Beckermet Mine; Ullcoats Mining Co. (which in 1917 became associated with Florence Mine – the last haematite mine still working in Europe at the time of its closure in 1968); Wyndham Mining Co.; Whitehaven Haematite Ironworks Co.; and Baird’s Knockmurton Iron Mines (you can still trace its raised track bed in the pastures south of Murton Fell).

Quarries include Clintz Quarry (near Egremont, now usually spelled Clints), Aldby Limestone Quarry and Rowrah New Limestone, while coal pits include Stirling’s Pits No.s 4, 5, 10, 12, the Lonsdale Mining Co, and Lord Leconfield’s No 4 Pit. Charles Wyndham, 3rd Baron Leconfield – whose wealth partly derived from the minerals of Cumberland – owned Cockermouth Castle and Scafell Pike. In 1919 he gifted Scafell and its massif to the National Trust as a permanent war memorial to honour the soldiers of Cumbria who served in the First World War, among whose number was his son.

This article is taken from William’s new book Cumbria – 1,000 years of maps, available, signed, from Inspired by Lakeland and out next week.

Striding out: Mark Richards’ walk of the month

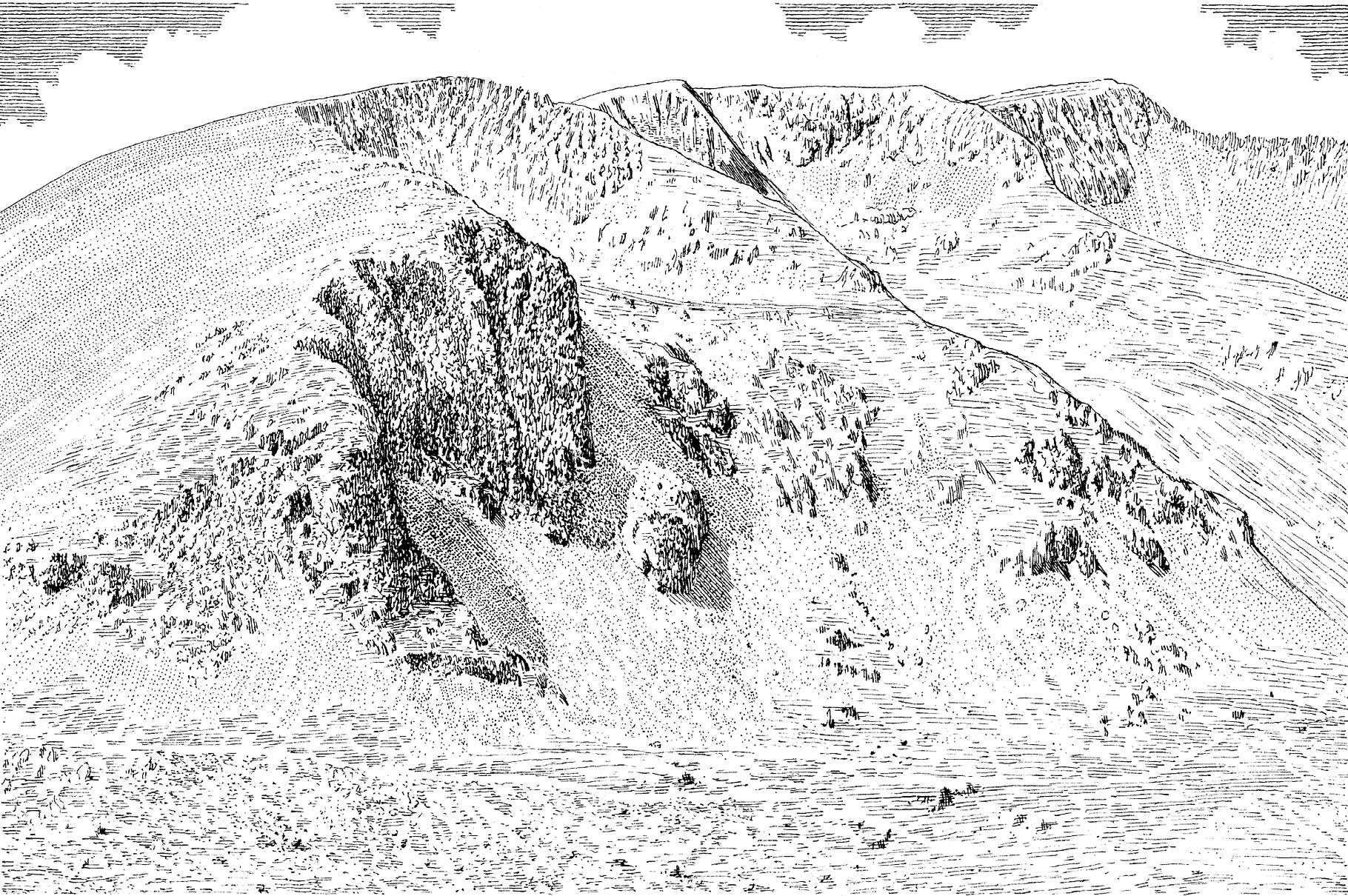

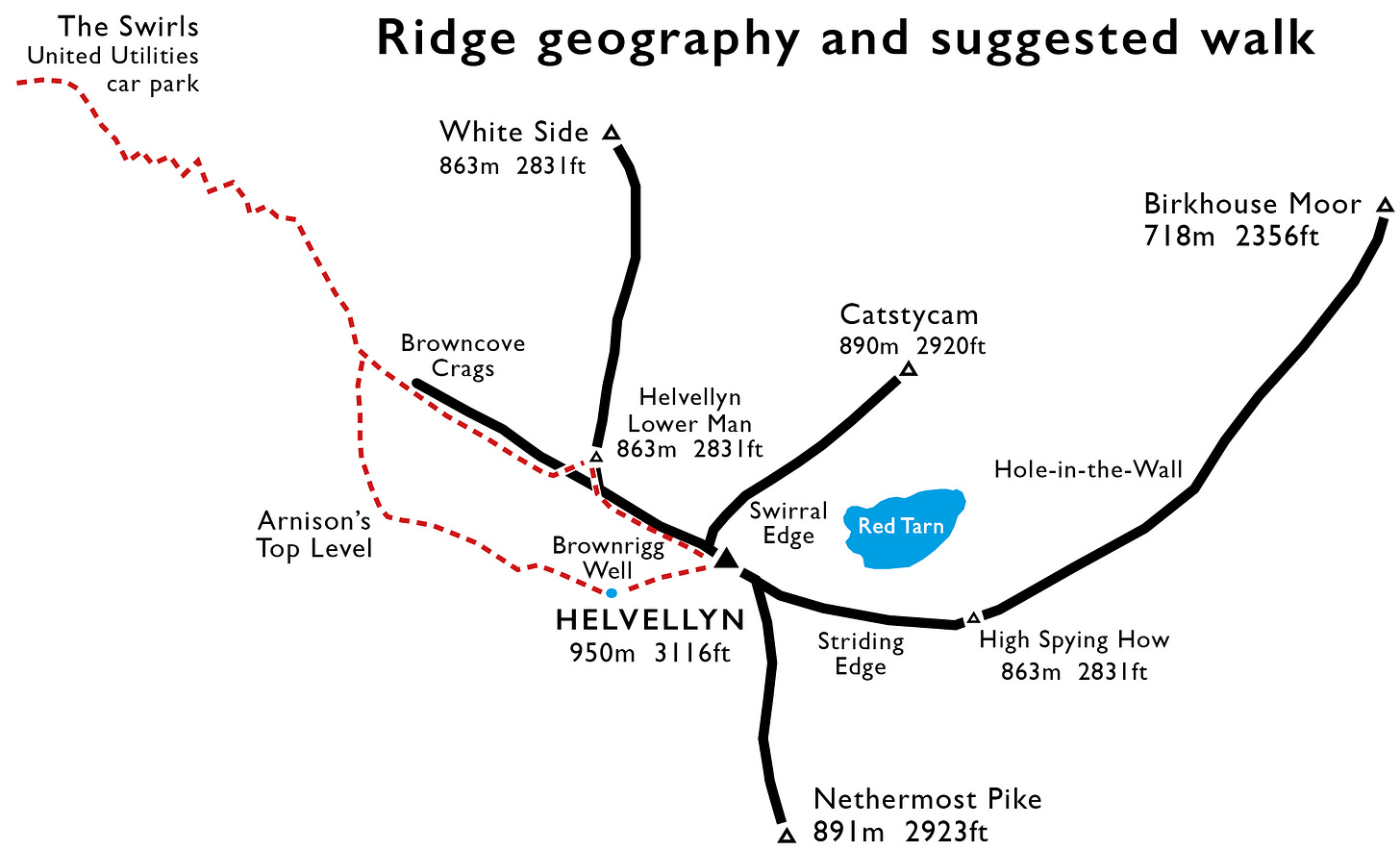

A secret ascent of Helvellyn – 4.5 miles, 2,532ft ascent

The majority of walkers who climb Helvellyn from Swirls pace with singular resolve directly to the summit. Connoisseurs may take a more pioneering approach by exploring little-known mines and a pristine spring before coming to one of Lakeland’s great summits.

Our adventure begins from the engineered zig-zags above Swirls car park, branching right from the popular cobbled path approaching Browncove Crags at a large split boulder. From here aim for a second boulder peeping over the near brow, then contour directly south along a sheep trod.

The Herdwick’s life is hard enough without expending extra effort on passage between grazings. As such, its trods lead economically across even the steepest of slopes. This one settles into a gentle rise, then contours along the brink of Helvellyn Screes above the cleft of Dry Gill with fabulous views down over Thirlmere. The terrace path curves into the upper Mines Gill valley, skipping over the top-most scree to arrive – bull’s eye – at Arnison’s Top Level.

Five mining levels pierced the flanks of Helvellyn below this spot, most yielding poor returns for the huge labours involved in accessing four thin lead veins: the Blue Vein, Old Vein (North South Vein), Eagle Crag Vein and the East-West Vein. Contrast the scanty spoils of these Wythburn Mines with those around Greenside on the eastern flanks of the range – though these workings boasted at least one claim to fame; the (likely) highest toilet in the Lakes, flushed clean during its 19th century heyday by the waters of the gill.

Continue now on a rising line into the upper reaches of Mines Gill valley (unnamed on maps), targeting the foot of a water-cut. Clamber up Whelp Side beside this narrow groove. It’s a channel little wider than a boot, etched by miners to provide additional water in dry periods – hard to imagine this year.

After a small wind shelter, the ground levels at Brownrigg Well. At 860m (2,822ft) this is the highest constantly-flowing spring in Lakeland, which has quenched the thirst of shepherds, walkers and in-the-know fell-runners for generations. The late, great Tony Greenbank recalled a conversation he once had with Grasmere farmer Peter Bland: “At Brownrigg Well you can fling yourself flat on the ground and sup safely knowing the Adam’s ale has arrived fresh from the bowels of the earth.”

Helvellyn’s OS column lies 500 or so paces east-northeast up the frost-fretted tundra slope. Unless fog-bound, the view around the compass is unifying in its completeness; few of Lakeland’s mightiest hills are hidden, and the cross-wall seat offers shelter whichever way the wind blows.

The name Helvellyn harbours portent and excitement in equal measure. Prosaically it is derived from the Brythonic (Welsh) helfa (hunting) and llyn (pool or lake). So, like the great Grampian mountain Lochnagar – ‘lake of the breast-shaped mountain’ – the name describes its corrie lake.

The fell is the culminating point of the highest continuous fell ridge running north–south through the National Park – a 15 mile upland high way between Threlkeld and Ambleside. Indeed, one of Lakeland’s most rewarding walks is that from Clough Head south to Ambleside, with a near-mid-way lunch spot alongside the shingle bays of Grisedale Tarn, resting place of King Dunmail’s lost crown.

The steep western slopes of Helvellyn, like so many on these eastern fells, contrast with the fiercely craggy eastern aspect. Like the horns of a bull, two arête ridges project from the summit plateau, both taunting red rags no ambitious fellwalker can resist: Striding Edge dropping to Birkhouse Moor and Swirral Edge leading to the elegant peak of Catstycam – best claimed on its own terms via its rarely-trod northwest ridge.

Our walk’s northwest return route along the brink of Browncove Crags should include the cairn on the crown of Lower Man, with its grand northern perspective of the range. One oddity emerges in descent: Browncove Crags overlooks the west-facing Helvellyn Gill valley, not east-facing Brown Cove.

Then it’s time to rejoin the tourist crowds in amiable descent to the car park, where the question these days is not ‘What did you make of mighty Helvellyn?’, but ‘Where is the Infinity Pool?’

You can buy Mark’s Walking the Lake District Fells guides from Cicerone.

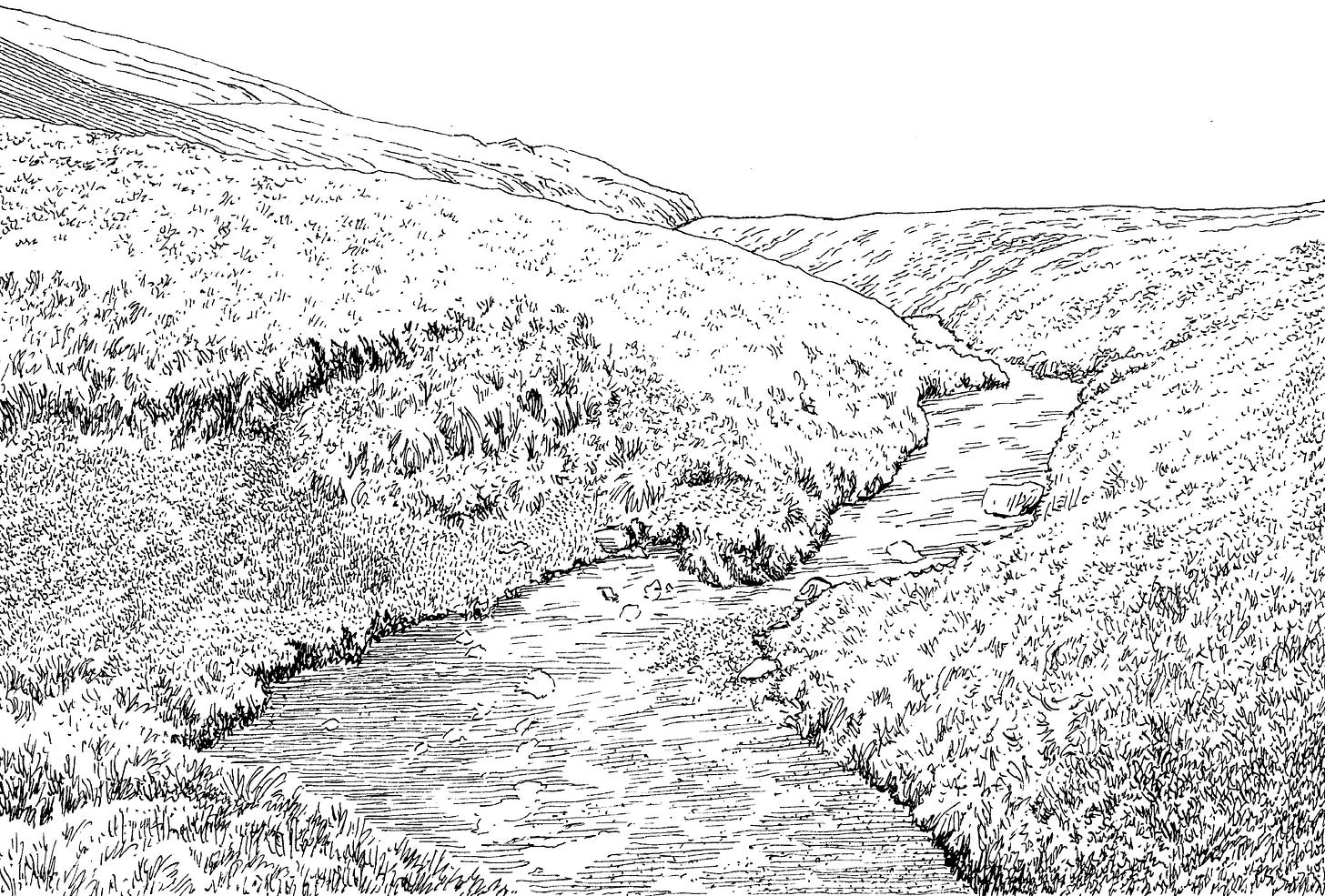

Cumbriana: The unexplained origins of Lucy Gray Lonning

A column of curiosities, with Alan Cleaver

When I moved to Cumbria in 2005, I added a variety of dialect words to my vocabulary: bait, yam, la'al and marra. I came to understand that crack is not always something to be avoided (even if it can be addictive). And I developed a passion for lonnings.

In one sense, a lonning is just another dialect term for a lane. But it is more specific than that; most Cumbrians understand a lonning to be a quiet, low-level and often short footpath or track. The term may have emerged from the dialect word loan, meaning ‘the quiet place by the farm’, where villagers would go to buy eggs and milk. The path to the loan became the loan-ing.

The lonnings that interest me most are those with a particular name – often ones known only to locals – such as Tatie Pot Lonning (Allonby), Bluebottle Lonning (Monkhill), Dynamite Lonning (Whitehaven) and Boggle Lonning (Wythop). Boggle – meaning ghost – was another word I added to my vocabulary.

Often the prefix refers to a lonning’s location – such as Church Lonning (Boot) and Tin Barn Lonning (Brampton). Sometimes it namechecks a former resident (Wardles Lonning – Lowca, Billy Watson Lonning – Workington).

Other names are harder to fathom. One of those is Lucy Gray Lonning; a charming, tree-shaded old way that descends alongside a stream from the hamlet of Derwentfolds west of Threlkeld to Whit Beck.

Who was Lucy Gray?

Older locals will tell you the centuries-old tale: young Lucy was sent out on a winter's night with a lantern to meet her mother returning from market, but a storm arose and the girl never returned. Villagers searched for missing Lucy in the morning and discovered footprints leading to swollen Whit Beck. Her body was later found downstream.

Lucy and her tale was immortalised by William Wordsworth in his 1799 poem ‘Lucy Gray', but he explained in his notes that the story was rooted in the West Yorkshire town of Halifax. His sister, Dorothy, lived in Halifax with the Wordsworths’ aunt Elizabeth after the siblings’ mother’s death in 1778 and later passed the local tale onto William.

So why does Threlkeld now claim it as its own? I have discovered one potential clue: Elizabeth’s surname was Threlkeld – she was ‘Aunt Threlkeld’. Did she originate from the Lakeland village, and did she tell young Dorothy the story, who mistakenly thought it was set in Halifax?

We may never discover the whole truth, but perhaps it doesn't matter; we have a delightful lonning to walk – and some good crack to go with it.

Discover some of the named Cumbria Lonnings on the definitive Google map compiled by Alan Cleaver.

Listen to Alan discuss lonnings and more on the now vintage CS#5.

Postcards from the past

‘Millican Dalton’, postmarked 1990, Keswick

“The Borrowdale Hermit and ‘Professor of Adventure’ Millican Dalton photographed by his friend Ralph Mayson in the 1920s on board his raft Rogue Herries sailing down the River Derwent in Borrowdale”.

Ralph Mayson sold his prints for many years at ‘Mayson's Photographic Emporium’ in Lake Road, Keswick (the former studio is a listed building). As a photographer-climber, Mayson also played an inaugural role in establishing the annual Armistice Day commemoration on Great Gable.

You can listen to our interview with Matthew Entwistle about the Professor of Adventure at countrystride.co.uk/single-post/countrystride-71-millican-dalton-caveman-of-borrowdale

These are brilliant!

By coincidence my post next Wed on aboutmountains.substack.com is heading up Helvellyn by a different unexpected route. Already scheduled as I'm at Gatwick en route to the Alps