Hefted newsletter #5: November 2024

Despatches from Cumbria and the Lake District, from the team at Countrystride and Inspired by Lakeland

In this month’s Hefted: a bumper News Gather features a hand grenade on Cat Bells, hill farmers’ views on the budget, Ulverston terror-otters and a library book returned 113 years late; Mark undertakes a low-level round of Crummock Water; Alan Cleaver gets into the Hallowe’en spirit with one of the county’s more terrifying ghost stories; and historic buildings expert Alexandra Fairclough picks her five favourite Cumbrian churches.

The gather: Pick of the Cumbrian headlines

Gavin Capstick, the Lake District National Park’s new boss, has promised to do “as much listening” as possible while shaping a refreshed vision for the future of the Park. “I think there is a really important role for me personally in listening to our local communities,” said Mr Capstick, who took over from Richard Leafe at the start of October. In a wide-ranging interview with The Keswick Reminder, the new chief talked about ‘permitted development’ pop-up car-parks, local housing pressures and the “tightrope act” of balancing the two purposes of National Parks.

Reactions to Rachel Reeves’ first budget from hill farmers have been largely negative. James Robinson from Strickley Farm (near Kendal), chair of the Nature Friendly Farming Network steering group, said of the new £1 million threshold for agricultural property relief: “I am concerned that Rachel Reeves thinks she has ensured that small family farms are protected with a £1 million threshold. Strickley is probably a smaller than average-farm, and yet we will be three times the threshold.” James Rebanks of Racey Ghyll (Matterdale) offered a forthright analysis of farm subsidies in a series of tweets on X: “When it comes to farming/food/nature restoration (and they basically come as a parcel in the UK) then we are a nation of idiots.” Striking a more positive tone was Neil Heseltine, of Hill Top Farm (Malham), who welcomed government commitment to the new Environmental Land Management Schemes: “It is brilliant news that the DEFRA budget has increased overall and that there is a continued commitment to sustainable and nature-friendly farming. The agricultural property relief is a difficult topic… It could mean the super-rich will be less inclined to buy land simply for inheritance tax reasons.” Amidst the shouting, Sue Pritchard, CEO of The Food, Farming and Countryside Commission has written a thoughtful piece adding context to the backlash: “In a classic ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’ moment, removing agricultural property relief has triggered a huge outpouring of distress from UK farmers. Of course it’s not just about this. Many farmers have been buckling under the strain of change over the last seven years.”

Cumbria Wildlife Trust has reached its Skiddaw Forest fundraising target just six weeks after announcing its intention to buy more than 3,000 acres of the Back o’ Skiddaw. CEO Stephen Trotter said he was “delighted” by donations of £1.25 million that will allow the charity to establish England’s highest nature reserve. Restoration plans will create “a mosaic of healthy, resilient and revitalised mountain habitats”, including 620 acres of new Atlantic Rainforest. The Trust is now fundraising for restoration funds.

Ulverston is being terrorised by otters. Former operations manager Nigel Cooper, 61, lost “four goldfish, two Koi and three Northern Goldfish” after an otter raided his garden pond. “My wife squealed and I thought there was a burglar,” he said. Mr Cooper is now attempting to map local otter movements reported by other residents. More from MailOnline.

Dozens of Cumbrian pubs have been namechecked in the 2025 edition of CAMRA’s Good Beer Guide. The publication – the definitive resource for real ale enthusiasts across the UK, now in its 52nd edition – features more than 60 pubs from around the county, including 42 in south Cumbria, three in Keswick and six in Carlisle. Perennial favourites include Golden Rule (Ambleside), Black Bull Inn (Coniston), The Wainwright (Keswick) and Last Zebra (Carlisle).

A proposed new car park at Ullock Moss, Portinscale, is back before National Park planners for the fourth time. Mike Anderton – on behalf of Lingholm Private Trust – has submitted updated plans for a 150-vehicle car park to address what the planning documents refer to as “well documented” parking problems in the Cat Bells area. Local campaign group The Derwent Safe and Sustainable Transport Group – one of the key objectors to an earlier iteration of the divisive plan – told Cumbria Crack in 2023 that: “The responses to the second failed application showed that 90 per cent of Portinscale residents who responded opposed it.” Meanwhile, Lorayne Wall, lead planner at Friends of the Lake District, said of the latest plan: “Building car parks every time there is an increase in car numbers undermines any efforts or vision of a sustainable means of getting visitors to and around the Park.” Details of the car park’s long history can be found here.

…and plans have been lodged with the National Park for a number of road changes around Windermere in preparation for the proposed ‘Windermere Gateway’ development. This major new development, which will add 250 houses to National Trust-owned land below Orrest Head, alongside office space for the Trust and “a world-class entry point and transport hub to the Lakes”, was agreed in the 2021 Local Plan after examination by Government Inspectors following a string of objections over scale, sewerage infrastructure and amounts of affordable homes. More about the Gateway here.

Just six months after re-opening, the Thirlmere west road has been temporarily closed due to a rockfall. The road, which had been inaccessible for two-and-a-half years following Storm Arwen because of a perceived risk of rock and tree falls from Rough Crag, was opened in May after a campaign led by Ambleside’s Mark Hatton. On the Keep Thirlmere Open Facebook page, Mark wrote of the five-day closure: “Good to see the rockfall was cleared, the road inspected and the decision to reopen was taken within five days.”

A reminder that the Countrystride team are gathering in Ambleside on Wed 4 December for the first ever ‘Cumbrian Christmas Cracker’ – a seasonal evening of readings, poems, dialect and music with Alan and Lesley Cleaver, Sue Allan and The Cumbrian Duo. Tickets are available here: https://www.countrystride.co.uk/cslive

Previously unseen data has revealed that the illegal dumping of raw sewage into Windermere “went on for far longer, and was far more extensive” than originally thought. More than 140 million litres of waste was pumped into the lake from the Glebe Road Pumping Station between 2021 and 2023 at times when it was not permitted, according to analysis by the BBC. Commenting on the findings, Matt Staniek of Save Windermere said: “This isn’t just an environmental disaster – it’s an industrial-scale dumping operation.” More from the BBC.

A suspected hand-grenade has been removed from Cat Bells. The device, identified by a walker on the northwestern fell, prompted Keswick Mountain Rescue’s 120th callout of 2024. According to log notes: “Details of the object were recorded by the police, who then passed the information on to the relevant authorities... As a side note, and in the line of duty, the officers managed to claim Cat Bells as their first Wainwright.” More from Keswick Mountain Rescue.

A legal challenge against the dualling of the A66 has been rejected. Campaign group Transport Action Network (TAN) had asked the High Court for approval to challenge the former government’s decision to approve an upgraded 18-mile stretch of the trans-pennine route between Penrith and Scotch Corner. Dismissing TAN’s case, Mr Justice Mould said the then-Secretary of State had “found a compelling need for the development to take place”. TAN, which supports the transition from private to public transport, has questioned the safety gains of the scheme and argued that dualling the A66 will damage protected landscapes, increase carbon emissions and not deliver the scheme’s promised economic benefits. It has also warned of increased tourist numbers arriving into the Lake District. More from the BBC.

Borrowdale Banksy is back… with a new “elegant stone ring” discovered below Bannerdale Crags in the northern fells. More from The Keswick Reminder.

Grey squirrels are being released from traps by animal rights campaigners, further endangering the native red. Robert Benson, chair of Penrith and District Red Squirrel group, said the group was dealing with “an explosion in grey numbers” but that traps were being opened and trail cameras vandalised. “Local people understand [what we’re doing], but people visiting from further south see grey squirrels as part of our wildlife and don’t see what a threat they are.” More from the BBC.

Film-maker (and red squirrel champion) Terry Abraham has announced the subject of his next Lakeland documentary. Following in the footsteps of his Life of a Mountain trilogy, the new film, with the working title Born of Fire and Ice, Shaped by Water will, according to Terry, “follow the journey of a raindrop landing atop Scafell Pike to the sea.” More, including a teaser video, from Terry on Facebook.

Long-term National Trust ranger Roy Henderson – featured in Countrystride #9 and #99 – has retired. Roy, who covered Borrowdale for 42 years, and who has clocked up 29 years in Keswick Mountain Rescue, counted among his achievements the hydro schemes at Watendlath and Coombe Gill and improved access to the valley’s paths. In The Keswick Reminder his colleague Melinda Gilhen-Baker writes: “There isn’t a hedgerow in Borrowdale which Roy has not helped to plant or lay; he knows every crag and woodland, every path and every beck; and he has a fondness for the place I have yet to see matched.”

Meanwhile, two members of the Cockermouth Mountain Rescue team, Dan Roach and David Binks, have been profiled in Wired magazine for developing a groundbreaking piece of piloting and image analysis software that uses pre-programmed flight paths to help drones find missing people on the hill more efficiently. More from Wired.

A Grange-over-Sands resident has described the moment that “a rock the size of a tennis ball fell from the sky just a few metres away from me” after an unannounced controlled explosion at a nearby building site. The unnamed resident said: “I thought I was in a war zone.” More from The Westmorland Gazette.

A possible “breakthrough” in the local housing crisis has been announced by a Cumbrian housing trust. A planning restriction developed by the Lakeland Housing Trust could enable Lakes homeowners to ensure their home remains occupied by local people in perpetuity. The Trust has spent two years working with solicitors to develop a restriction which people can choose to register with the Land Registry against the title of their property. It means the sold home could not be used as a second home, holiday let or Airbnb. More from Lakeland Housing Trust.

Carnforth Heritage Centre has been saved from closure thanks to the efforts of a new local group. The Centre, based on platform 1 of the station immortalised in David Lean’s 1945 film Brief Encounter, and which displays a wealth of railway memorabilia, was due to close on 12 October. David Koller, from the steering group, said: “There is massive, massive global support for Brief Encounter.”

Brookside and Royle Family star Eric ‘Ricky’ Tomlinson has discovered he has family roots in Ambleside. The Liverpudlian actor was told on the ITV’s DNA Journey with Ancestry that his great-grandfather was social reformer and tailor James Hunter, born during the Lakeland town’s literary heyday in the early 19th century. More from The Westmorland Gazette.

…in other Lakes-celeb news, James Middleton – brother of Kate – has revealed the “great connection” his family has with Lakeland, and the role the fells have played in managing his mental health. “There was a point at which I was in a very bad place, and I disappeared for a few days and went to seek solace in the snowy Cumbrian mountains. I got to the top and I cried; I shouted; I unleashed so many emotions.” His favourite fell is Coniston Old Man and his must-visit pubs are Old Dungeon Ghyll and The Drunken Duck. More from The Standard.

…and finally, a book has been returned to a library in St Bees – 113 years overdue. A copy of the Poetry of Byron was withdrawn from St Bees School library on 25 September, 1911 by former pupil Leonard Ewbank who left the school in 1911 and who died during the First World War. More from The Guardian.

Striding out: Mark Richards’ walk of the month

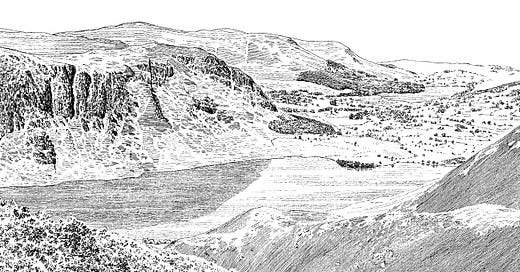

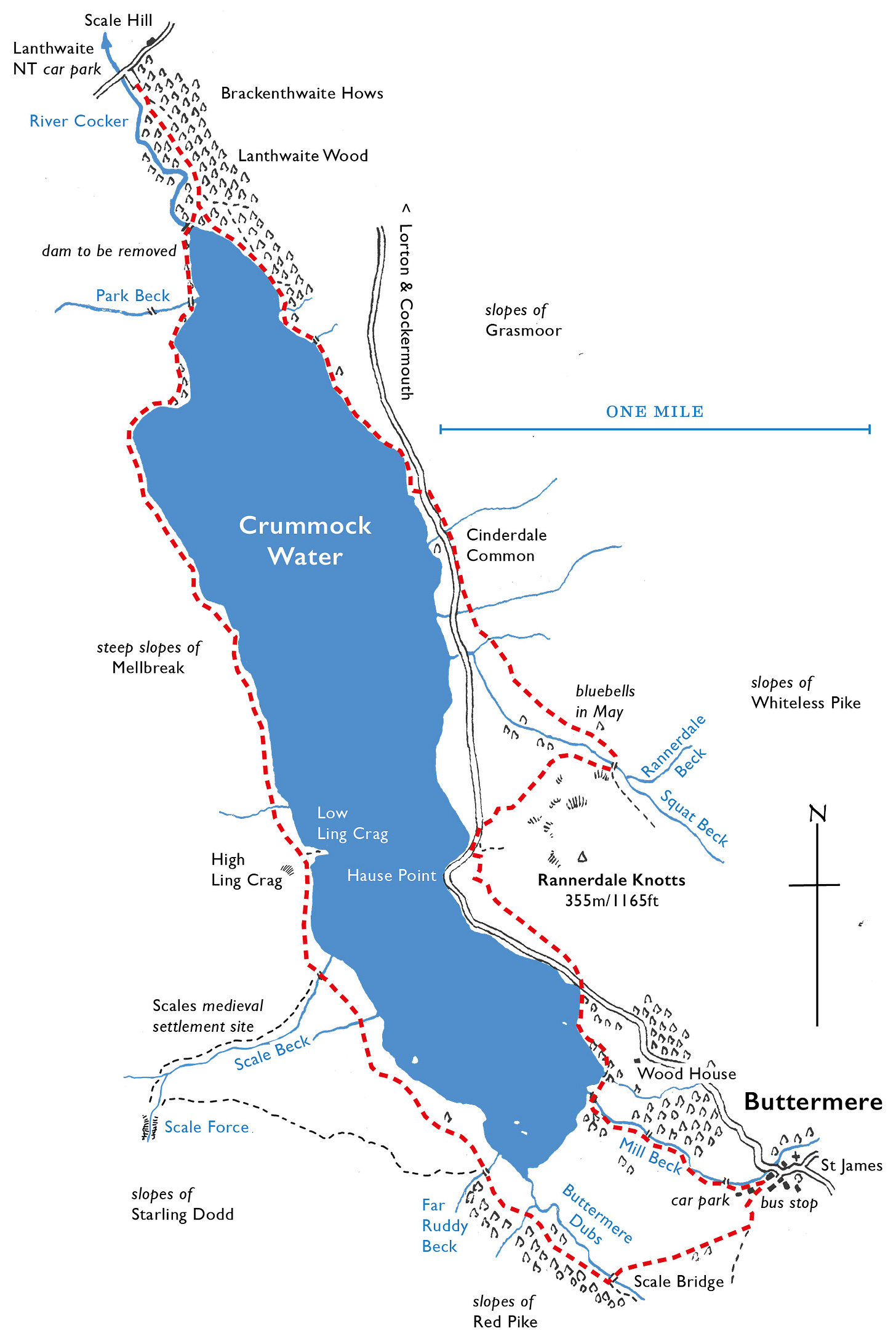

The Crummock Round – 8.5 miles, 550ft ascent, 5 hours

Mark’s autumn walk is a round-lake wander that ensures constantly changing perspectives of an ever-changing fell surround. There’s history aplenty to enjoy – some of which is even based on fact…

The National Trust’s Lanthwaite Wood car park makes the ideal springboard for this valley-based wander around Crummock Water – enjoyable at any time of year, but especially so in the back-end when the leaves are turning.

On a personal note, this western valley has long held a special place in my heart; my wife and I stayed at Scale Hill when it was a hotel on our honeymoon in 1975, recording our first ever visit to the foot of Crummock. It would be 27 years later that we made the move north to settle in Cumbria.

Leaving the car park, Lanthwaite’s woodland paths keep to the Water’s east bank path, which comes by a boat house on the shore. If the water is not too high there is a good line reasonably close to the water’s edge, which threads through trees and soon becomes a steady path.

Brackenthwaite Hows – the hidden hilltop above the wood – is one of the National Trust’s most recent Lake District acquisitions, purchased for £202,000 in 2019. The original Viking township of Brackenthwaite (‘the clearing in the bracken’) includes the mighty peak of Grasmoor and all the slopes between Lorton and Buttermere.

The Hows has long been a cherished viewpoint over Crummock Water. When Keswick entrepreneur Peter Crosthwaite located Father Thomas West’s ‘viewing stations’ on his intricate tourist maps of the late 1700s, he went further in Lorton vale – a valley West had not covered – adding six stations to his Accurate Map of Buttermere, Crummock & Lowes-Water Lakes; Scale Force etc. One of them is Dob Ley Head on Brackenthwaite Hows, from where attention is drawn across the lake to Mellbreak.

Emerging from Lanthwaite Wood, eyes shift left to the towering pyramid of Grasmoor End. The western slope looks impenetrable from this angle, though Wainwright identified a breach through the crags and heather. I did the same in my Buttermere volume of Walking the Lake District fells – Route 1 up Grasmoor End is an adventurous but entirely achievable line of walking/mild scrambling.

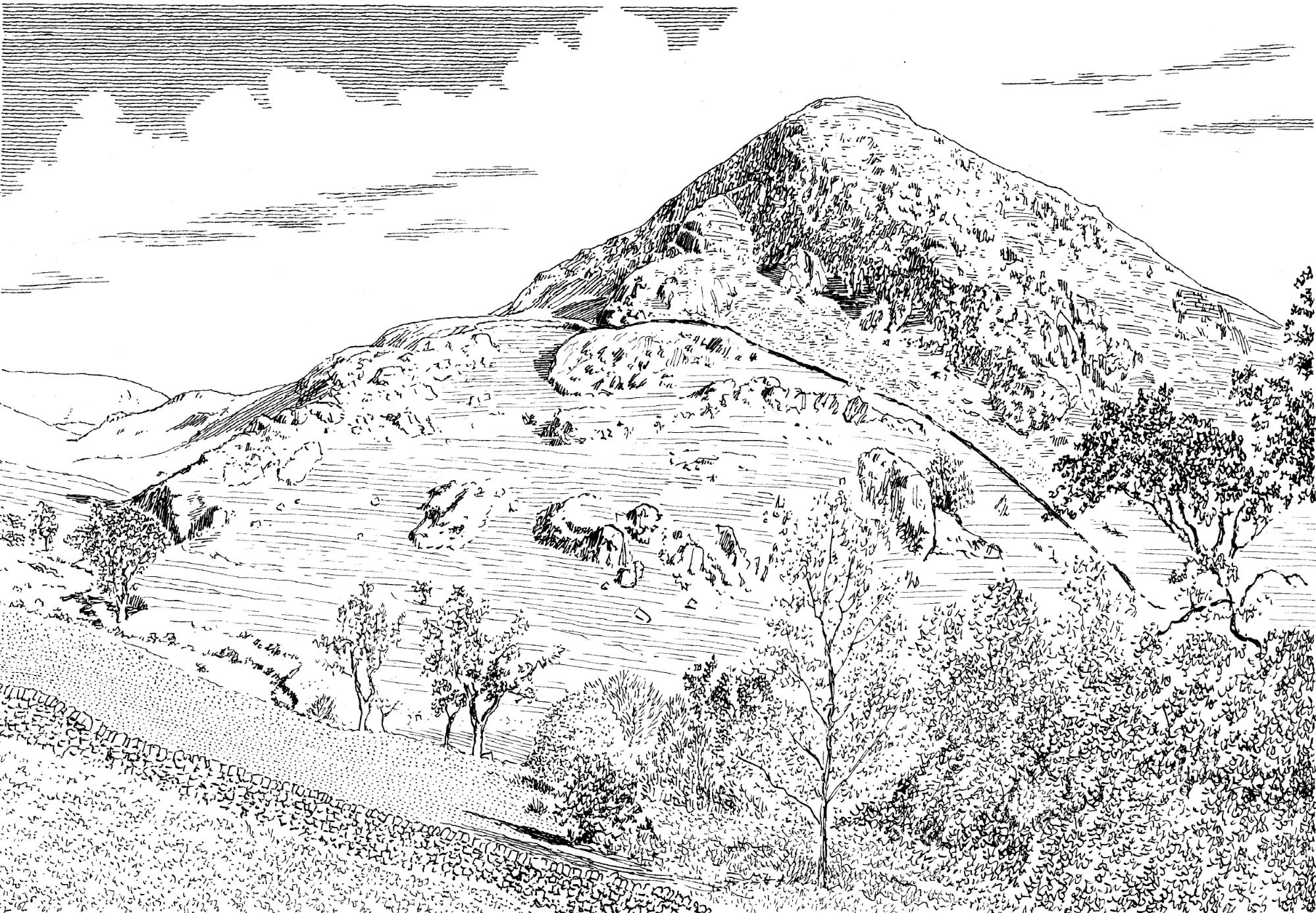

The path dips and rises by a wall onto the open road across Cinderdale Common. Stride through the parking area; in late spring this gets filled when the Rannerdale bluebells burst upon the scene in the open-secret side valley ahead. The path marches on to a hand-gate with a grand view over the carpet of blue.

The place name Rannerdale relates to the old path that clambers up the bank close to Hause Point. The Register of the Priory of St Bees has this as Ravenerhals in 1170, which translates as ‘the pass of the shieling [summer dwelling] haunted by raven’. Keen eyes may spot an aged crab-apple tree in this vicinity, nestling amid outlines of medieval dwellings above the tidy order of dale-floor pasture. This was likely the settlement that adopted the name, which was subsequently deserted by 1547.

The path crosses a footbridge, from where veer right and run on down by the meadow-bounding wall. After a concrete platform, spot a ‘smoot’ in the base course of the wall down right; in days past a trap would be set in this tight passageway to catch rabbits for the farmer’s stew.

Coming onto the road again and thence to the lake edge, note a waymark post, left, and stone steps clambering up into the bracken. Keep to the right-hand zig-zag; this is the bridleway to the ancient hause, which avoids the road and blind bend at Hause Point.

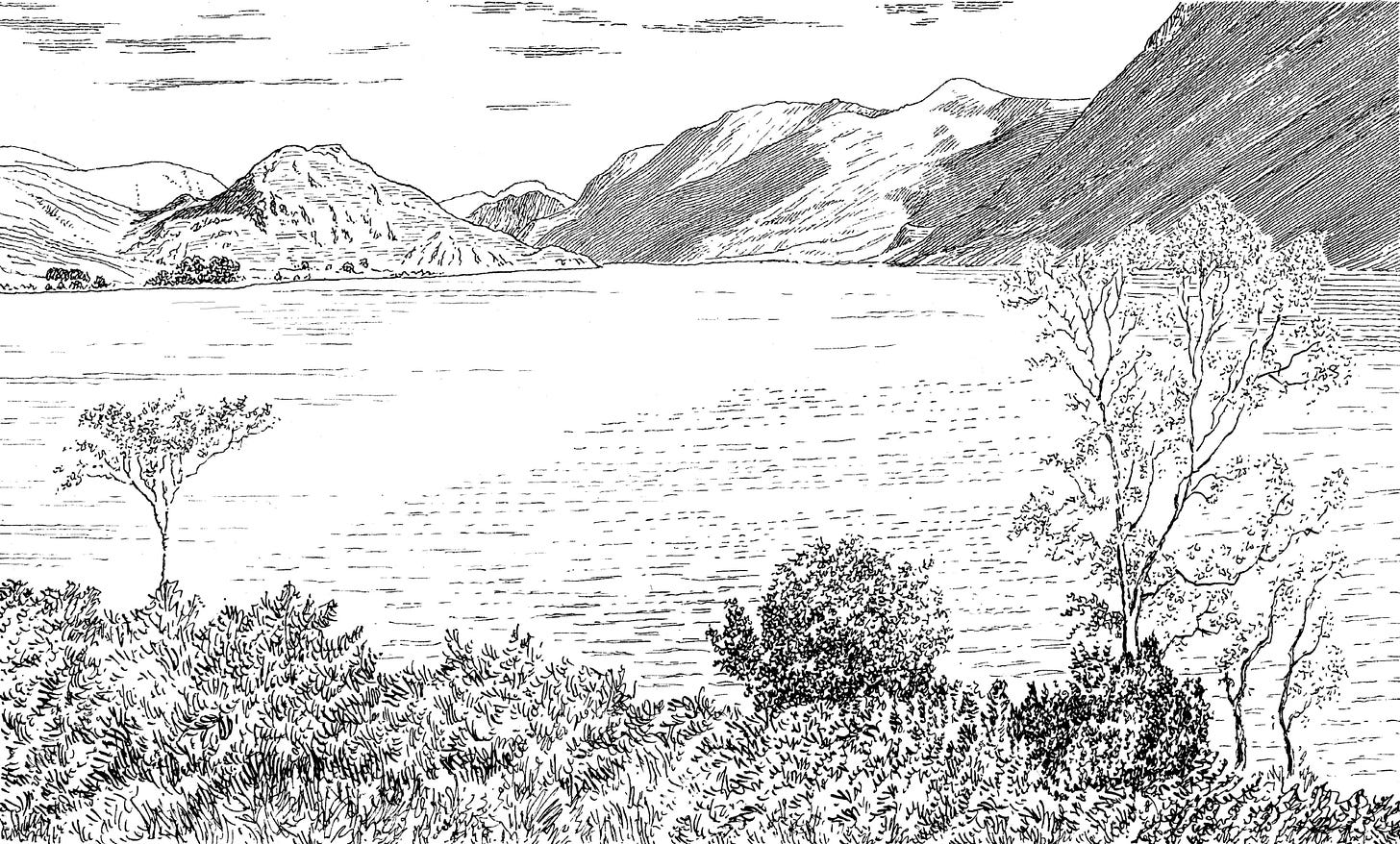

Ahead – and over the lake – the oak-wooded slopes climbing the High Stile range (golds and browns during these few weeks) excite attention, as too the approaching head of the lake.

Coming onto the road, cross it and step down by a hand-gate, from where the footpath tracks the shoreline through watermeadows, soon rising to a further gate on a wooded ridge below Wood House – painted by J. M. W. Turner in 1798, now guest accommodation owned by the National Trust. Cross two footbridges, the latter spanning Mill Beck (the lower part of Sail Beck, that rises in the saddle between Sail and Ard Crags), whereupon turn upstream and left to come by a camping ground and arrive in the heart of busy Buttermere.

The village name matches Grasmere in describing a lake surrounded by lush pasture, reflected here in the Old English term ‘butter’, which records the area’s dairy past. Syke Farm maintains the traditional link by serving home-made ice cream – produced using milk from the farm’s Ayrshire dairy herd.

This little village has long attracted big characters.

Liverpool-born Nicholas Size (1866–1953), one-time owner of the Victoria (now Bridge) Hotel, was an entrepreneur of the grandiose kind, with a capacity for myth-making to enhance his tourist interests. Sharing the antiquarian passions of the Grand Tour age, he invented a Viking battle in Rannerdale, published in his 1929 novella The Secret Valley, and sought to transform the village into an Alpine resort with a golf course (which he did build) and a chairlift to carry visitors onto High Crag (which he did not). Size – always a Marmite figure in Buttermere circles (“he'd do anything to make money,” noted one local) is buried in the woody ‘fairy glen’ that embowers Mill Beck east of the valley road.

Earlier tourists were lured over Newlands Hause by more salacious interests: the promise of being served ale at the Fish Inn (now Buttermere Court Hotel) by Mary Robinson (1778–1837), the legendarily beautiful ‘Maid of Buttermere’. It was writer and explorer Captain Joseph Budworth – ‘A Rambler’ in The Gentleman's Magazine – who first ‘discovered’ Mary, noting her “fine oval face, with full eyes and lips as sweet as vermillion”. For the bigamous John Hatfield, those eyes and lips proved a fatal attraction. His life ended on the gallows at The Sands, Carlisle in 1803. Mary, meanwhile, abandoned Buttermere – and her unwanted fame – for a quieter life in Caldbeck, where she married, legally this time, farmer Richard Harrison. She is buried in the churchyard of St Kentigern.

The walk leads from Court Hotel along a farm lane that crosses the the fertile alluvial plain between Crummock Water and Buttermere, then follows the track signed ‘Scale Bridge’. This stone bridge spans Buttermere Dubs – the watercourse that links the two water bodies; dubs means ‘dark pools’, and in quiet times otters may be seen here.

An undulating and oft-rough path leads north. After crossing Far Ruddy Beck, a thin path draws across the slope, left, to access one of the star attractions of the valley: Scale Force within its tight gorge. At 170ft/52m, it is the tallest single-drop fall in Lakeland, though reaching its intimate viewpoint is not everyone’s idea of cosy or comfortable excursion. Set in this broad side valley – home to lonely Floutern Tarn – are the remains of the medieval settlement of Scales, with evidence in excavation of iron ore smelting, alluded to across the lake in the name Cinderdale Common.

Continuing along the lower path, cross the footbridge over Scale Beck and stroll onto the peninsula of Low Ling Crag, with its little bay and low domed extremity an ideal spot for picnics. It is one of Lakeland’s loveliest swimming spots.

The continuing path is largely set back from the shore below the shadowed, scarred bank of Mellbreak. The fell-name is difficult to translate. It looks initially to originate from the Irish-Gaelic Meall breac, meaning ‘bare dappled hill’ (there is a Maulbrack in County Cork). But others will claim the Norse melr (‘sandbank’) and brekke (‘hill-slope’). By this definition the fell is identified not by its physical presence, but by its base, which would seem odd for a mountain of Mellbreak’s character. The long saddleback ridge of heather and scree is a striking presence in a valley of fine fells, which rather swings weight behind the suggested Irish roots. The continuing path crosses a gravel bay then enters fringed woodland to cross Park Beck, the outflow of Loweswater.

This final half-mile back to base will soon have a different feel. Crummock Water’s outflow was first dammed in 1879 with a timber weir. A larger masonry dam was erected two decades later, raising the lake level by 60cm so that its crystal-clear waters could be piped to Silloth, Maryport and Workington. The present right of way makes use of that old infrastructure.

With the West Cumbrian Pipeline now channelling Thirlmere’s waters north and west, consultations continue over the removal of Crummock Water’s dam, with United Utilities, Natural England, the LDNPA and other groups working to restore the lake to its ‘natural level’. Identifying exactly what its natural level is is an interesting academic exercise (it will be around 1.35 metres lower), and there are implications not only for nearby landowners, but also walkers, who will need a new footway to access the east shore path. There are aesthetic considerations, too; a new bare tideline will take time for nature to reclaim.

One notable benefit of a lower shoreline may be the creation of a more consistent shore path – particularly below the road at Hause Point and below Rannerdale Farm. Local Ramblers are already lobbying for greater access, which could make this already superlative walk finer still.

Mark is author of four Countrystride Walking Companions, each featuring dozens of walks, line illustrations and insights into local landscape, history and heritage.

For more about the Buttermere valley, Countrystride #30 takes a virtual tour of ‘the secret valley’ in the company of Angus Winchester.

‘The Pimp’*: Five of the best…

Cumbrian churches

As picked by architectural historian Alexandra Fairclough.

#1. St Bega, Bassenthwaite

The first churches in the UK were built as far back as AD597 following the arrival of missionaries despatched from Rome and led by the ‘Apostle to the English’, Augustine of Canterbury. Thus began the Christianisation of the Anglo-Saxons.

The first of my five chosen Cumbrian churches is diminutive St Bega on the shores of Bassenthwaite Lake. It dates to AD950 and is one of just three in Britain (all in Cumbria) named after the Irish princess and anchoress who – legend has it – fled her proposed marriage to a Norse chieftain by crossing the Irish Sea for the Lakeland fells.

The square planned building may sit on older foundations. There is evidence of phased development, with Roman walling in the north and east walls, and a pre-Norman chancel arch on heavy pillars. The building was extended in the 13th century and restored in 1874.

Architecturally of simple form, it is the location that makes St Bega so special: solitary and waterside, it is strikingly beautiful when viewed from within the Mirehouse Estate, from across Bassenthwaite Lake or indeed from on high, as from Skiddaw or Dodd.

The church also has a number of literary connections. It features in Wordsworth’s A Guide to the English Lakes, and it is likely that the opening of Tennyson’s epic poem Morte d'Arthur takes inspiration from it (“Sir Bedivere… bore him to a chapel nigh the field… That stood on a dark strait of barren land.”) More recently, Wigton-born broadcaster and author, Melvyn Bragg, set his novel Credo here.

#2. St Michael’s, Burgh by Sands

Built on the site of the historic Roman fort of Aballava close to the line of Hadrian’s Wall, St Michael’s church has evidence of Roman masonry in its walls. Dated to the 12th century, it is built of red and calciferous sandstone with a green slated roof and has a simple plan form with nave, chancel and a side aisle.

So far, so regular.

What makes St Michael’s unusual is its defensive past. The building of today is dominated by its tower – a fortified pele tower, used as a protective haven for the local community when reivers drove south from Scotland. The walls are thick, with narrow window slots at ground floor level and small lancet windows on the first floor to prevent intruders. The tower also has battlements.

These features notwithstanding, today’s church reflects the settled history of more recent centuries. Originally St Michael’s had two defensive towers – the existing west tower and another at the east end. As such the church has no east window. This is highly irregular; churches were designed to face east towards the rising sun, where beams striking the east window during morning services represented the light of God.

My favourite part of the building is the ‘yett’ – an iron gate that prevented access in times of attack to the tunnel-vaulted ground floor room and first floor above. There are plenty of other fascinating features, too, including a Norman doorway with unusual ‘beakhead’ decoration, carvings of animals above the tower doorway and five stained glass windows by Heaton, Butler and Bayne, one depicting King Edward I, who was slain in 1307 on the nearby Solway marshes – another reminder of the area’s bloody past.

#3: The Priory Church of St Mary & St Michael, Cartmel

This priory church is part of the former monastic complex of buildings that survived the Dissolution in 1537. It is a fine example of a late 12th-century priory church combining Romanesque and early gothic architecture, with important elements of later gothic architecture dating from the mid-14th century (the town choir) and the 15th (the nave and windows). The church is built of stone to a cruciform plan. The earlier phases of construction are easy to see as they use dressed sandstone, unlike the later 16th century rubble additions.

The building is as fascinating for its architectural features as its contents and craftmanship. There is a fine round-arched inner doorway at the entrance of the south porch and fabulous timber screens, choir stalls and misericords.

Misericords (or ‘mercy seats’) are small wooden shelves carved into the underside of folding seats on which priors could support themselves in a part-standing position during their six to eight services of prayer each day. Despite being hidden beneath seats, misericords often feature ornate carvings, which are not necessarily religious in nature. In some cases the carvings are subversive, featuring secular (sometimes bawdy) imagery. I particularly like the green man scenes in the Priory Church (below) – the green man is one of the most enduring pagan symbols, depicted as a male head peering through foliage.

Of equal interest are the ‘hatchments’ displayed on the north wall. A hatchment is a diamond-shaped board made of wood, or wood and canvas. It bears the arms, crest or motto of someone who has died, and would be carried in front of a funeral cortege before being displayed on the wall of a church in their honour. The hatchments here are those of the Cavendish and Lowther families, owners of nearby Holker Hall.

A final treat in this church of many fascinations are the sculptures by Josefina de Vasconcellos (1904–2005), former resident of Little Langdale. I particularly like ‘They Fled by Night’, which depicts Mary and Joseph asleep, with infant Jesus awake to the beauty of the night. It represents the hazards and hardships of all who travel to a strange land as refugees.

#4: St Mary’s Church, Wreay

Unusually, St Mary’s church in Wreay was designed by a Victorian woman architect – Sarah Losh (1785-1853) – and it is highly original in both design and detail. Replacing an earlier dilapidated church, it was built in the 1840s as a memorial to Losh’s late sister and parents.

Early churches had a simple rectangular floor plan, which evolved incrementally over time into other layout types, including the popular cruciform plan typical of the gothic style. Sarah’s vision, however, was of an entirely different church, based on her Grand Tour travels through Europe.

Her chosen design was inspired by a Roman basilica, with a rectangular nave and semicircular apse. The basilica style was popular in early Christian worship, especially in Italy, and was distinctly different to the gothic architectural tradition prevalent in northern Europe.

The focus of the building is the apse: a semi-circular recess decorated to reflect the last supper. The altar table is surrounded by a colonnade of columns between which there are 13 places set for Jesus and his 12 disciples. Above the apse arch is a row of angels, and palm trees depicting paradise.

If Losh’s layout in this remote Cumbrian village was a statement, then her unique artistic vision is revealed in the detail. Carvings of animals, plants and insects adorn every wall. The font is set with grapes, wheat ears and a dove with an olive leaf – a lively mix of classic Biblical symbolism twinned with motifs from nature. The mirrored lid to the font recreates a pond with waterlilies. There are pine-cones on the roof and on door handles (the cone is a symbol of fertility and regeneration, and a personal tribute to Losh’s friend William Thain, killed in the Afghan Wars of 1842 – he reportedly sent Sarah a cone before his death). The lecterns are carved (by Losh’s gardener) into the forms of an eagle and a pelican, and the pulpit is shaped like a calamite – a fossil tree.

Externally, the walls feature a number of carved animal heads, the window surrounds on the west end are decorated with natural forms from sea, earth and air and – striking an architectural note of fun – the chimney flue belches smoke from a stone dragon’s mouth. I’ve spent hours in this church and am still making new discoveries.

#5: St Martin’s Church, Brampton

St Martin’s is an Arts and Crafts-styled church designed by Philip Webb, the Pre-Raphaelite architect, in 1877–78. This was around the same time that he founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings – an important national amenity society that still champions the protection of historic buildings today.

Built in red sandstone with a green slated roof, square tower and lead spire, St Martin’s was designed in a ‘free Gothic’ style, which is to say it does not adhere to strict gothic ideals. Instead, Webb deliberately mixed styles: the open internal views are typical of neoclassical ‘Georgian’ church design; the ceiling is boarded, moving away from Pugin’s gothic rules; and the choir is within the nave rather than separated from it.

Internally St Martin’s is without architectural fuss: a simple worship space without chancel or pulpit. It is other features that shine – literally – like the outstanding stained-glass, designed by Edward Burne-Jones and made by the poet, artist, writer, and textile designer William Morris. Reverend Henry Whitehead, vicar of Brampton between 1874 and 1884, said of the windows – an early example of Art Nouveau – that “the time will come when strangers will seek Brampton, not for the sake of the town itself, but for the windows in St Martin’s church.”

Some churches leave you in awe; some evoke a cool kind of austerity; the reason I love St Martin’s is that it feels… homely. A low, dark and domestic-style entrance opens into an airy space coloured by the vibrant stained-glass windows, pale green painted ceilings and dormer windows. It is unusual – and difficult – for a church to generate an intimate kind of feeling; that is why I love St Martin’s.

Alexandra is an architectural historian, historic building conservation officer, heritage law specialist and RIBA architectural guide, as well as a Blue Badge Tourist Guide for Cumbria.

Countrystride visited St Mary’s Church, Wreay in episode #22.

* For the avoidance of doubt, ‘pimp’ is the number five in Cumbrian dialect.

Cumbriana Hallowe’en special: The Waterside Boggle

A column of curiosities, with Alan Cleaver

Have you ever seen a ghost? Around one in 200 people claim to have done so.

I have seen several during my professional life… but I was a reporter on the spiritualist newspaper Psychic News for a few years in the 1980s, so it was practically a job requirement.

Ghosts, like UFOs, seem to be on the wane these days, and seeking reliable accounts of sightings has never been without complications. Among the dozens of white ladies and black dogs reported across Cumbria – both now and in past times – there are only a handful of sightings that stand out. There are even fewer that get under the skin.

One of those that has always captivated me is the Waterside Boggle (boggle is an old dialect term for a ghost), as described by H. S. Cowper in 1897.

This famous boggle haunts the road beside Esthwaite Water, and Cowper’s report of this ghost was based on the recollections of an elderly lady (he doesn't name her) who claimed to have actually spoken to it.

Cowper wrote up her story in Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society thus:

“The story she told me as she sat in her cottage, over the fire, was a strange one. It appears that some 30 or so years ago, she went to live with her mother at the poor house... her mother being seriously ill and my informant having to nurse her.”

She told Cowper that one evening a man came to the poor house “dressed in his best Sunday clothes and held his hand out to me”. His hand was, she reported, cold as ice. The man then went to the mantel and struck a light with matches before leaving the house.

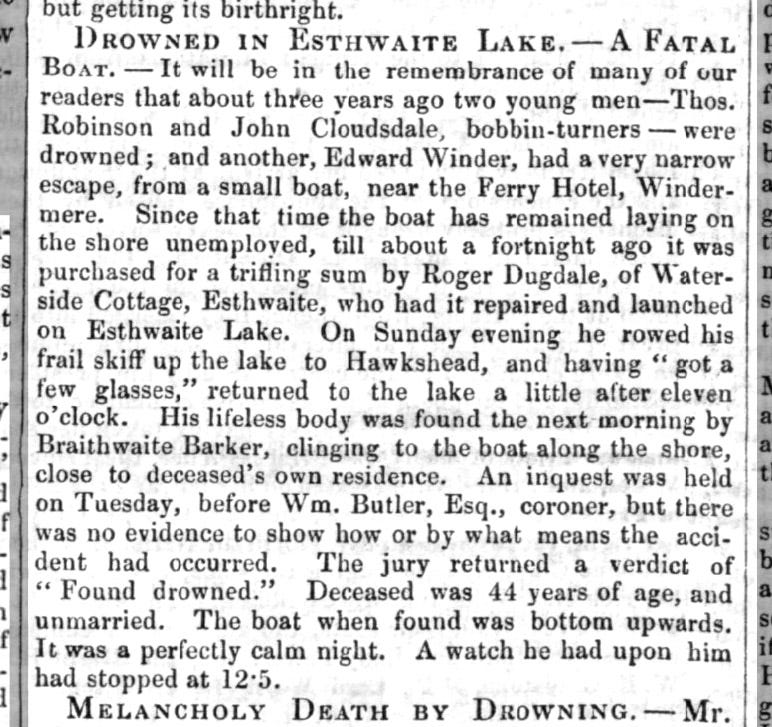

Later that evening the woman’s mother was struck with terror, and asked her daughter: “Whatever have you done?” She explained that the man was Roger Dugdale, a local man who had died (she believed murdered) some weeks before. Upon examining the mantle, the women discovered none of the matches had been lit. There was another twist. When Dugdale shook the woman’s hand, he whispered something in her ear – though she could not make out what it was.

The death of Dugdale (“44 years of age, and unmarried”) at Esthwaite is a matter of public record. The inquest found – as recorded in The Westmorland Gazette of 4 July, 1857, below – that he was “Found drowned” in the lake (not murdered). But if he had been murdered, perhaps his restless spirit returned to identify his killer? Was that what he muttered to the daughter?

It is a case that sends shivers down my spine, perhaps because of the detailed first-hand report and perhaps because of its ties to historical fact.

It also echoes something many witnesses of ghosts have told me: that the ghost they saw seemed quite real, and that they didn't realise it was a phantom until after it was gone. Would the woman ever have known she’d seen a ghost has her mother not recognised dead Roger Dugdale?

So next time someone asks if you have seen a ghost, don’t rush to say ‘no’. Perhaps a more accurate answer would be: “Not as far as I know”.

Postcards from the past

‘Buttermere and the Haystacks’, postmarked Cumberland, possibly 1972

A few more Scots Pines than today line the southeastern shoreline in the early ’70s – apart from that little has changed at the head of Buttermere. The postcard’s author is having a fine old time – and is losing weight…

“Spending two weeks in Borrowdale… The sun blazes down relentlessly day after day. I expect to lose about a stone on the mountains.”