Locked-down Cumbria: five years on

With the UK locked down during Covid, Cumbrian artists united to create work inspired by the unprecedented times. Five years on, we ask a handful how their art and lives have changed

Words: John Manning

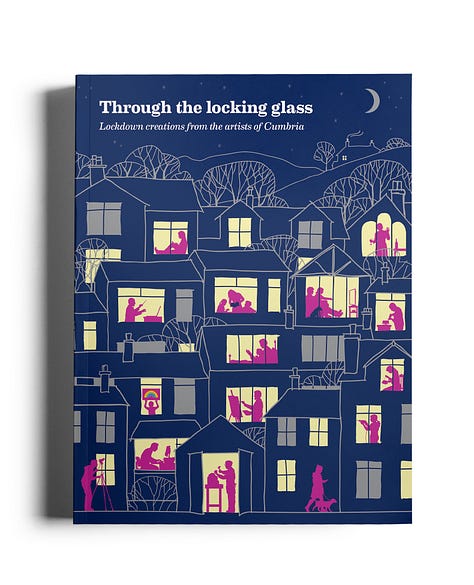

In June 2020, in the shadow of the first Covid-19 lockdown, Keswick publisher Dave Felton and Kendal illustrator Evelyn Sinclair put out a call to Cumbrian artists to gather creative responses to the pandemic. 200+ artists from around the county responded, submitting everything from prints to poetry, photography to sculpture, illustrations to fine art.

The resulting book, Through the Locking Glass – at once a story of human endeavour in exceptional times and a record of a unique period in history – showcased 80 of these pieces alongside a few words from each artist about their lives during that strange era.

Here we catch up with seven of the artists from the book, profiling their original work, then asking what has changed for them in the years since – in terms of art and their wider lives.

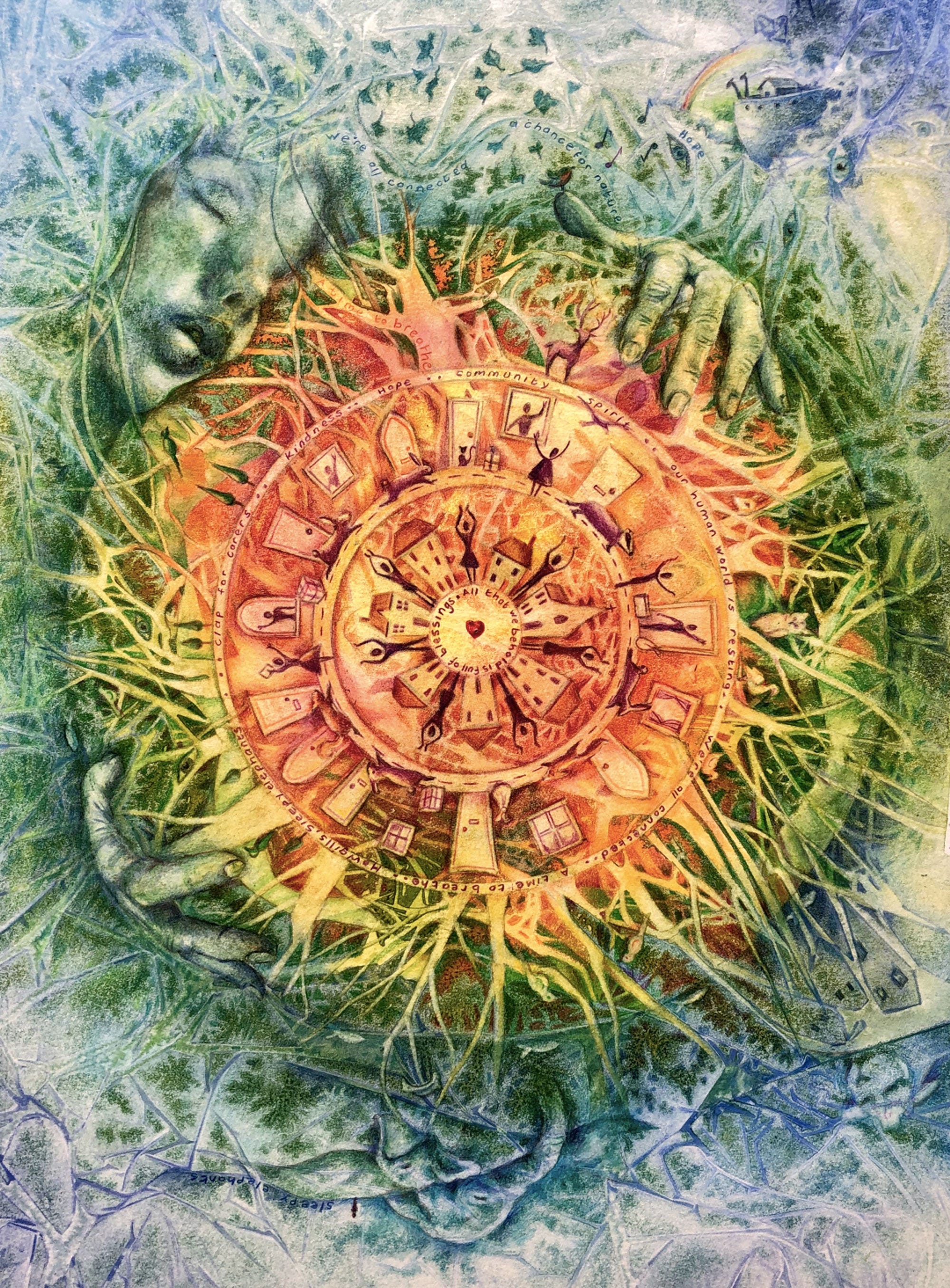

Ruth Clayton, Sedbergh

Ruth is a painter and illustrator who shares a studio with her partner, Stuart Gray, at Farfield Mill in Sedbergh.

Original artwork: Dear Elliot

What Ruth said then:

“What strange times we are living in. Initially the thought of lockdown was scary, and the idea of not visiting family devastating… But being isolated gave me time to stop, breathe, reflect and think. This is a historic moment in time and one that children will probably study at school in the future. So I started writing a diary to my 15-month-old grandson, Elliot, about my experiences. As I wrote, I realised there were things to be grateful for, and I tried to add at least one positive thought per diary entry. This gave me the initial idea for the illustration ‘Dear Elliot’.”

What Ruth says now:

“‘Dear Elliot’, the mandala I created for Locking Glass, feels like a time capsule – rooted in a moment. It captured things unique to that strange era: neighbours shopping for one another; animals reclaiming abandoned human spaces like railway stations. It spoke of a world briefly paused.

Humans are fragile, woven together by our need for connection. Even in isolation, we sought ways to reach each other: through Zoom calls, letters or distanced walks. Creativity became a bridge for me and others, and I hope that sense of holding on is reflected in my mandala.

During lockdown, Stuart Gray – my partner and a fellow contributor to the book – and I lived in separate lodges on a caravan site in Sedbergh. That quiet little corner of the world became our refuge, and I finally did what I had long promised myself – I began writing and illustrating a children’s picture book. My days were split between drawing and long walks with my dog. Sedbergh, with its open skies and quiet paths, was a gift. I often thought of those confined to high-rise flats and city blocks. We were lucky.

Post-pandemic, life and art have returned, but not without change. I stayed grounded, mostly. I’m a naturally optimistic person, but a close friend struggled deeply. To support her, we started setting weekly art challenges and sent each other voice messages every day. Those messages became a lifeline and, to this day, we still exchange voice notes. That small ritual is one of the most beautiful things to come from that time.

Emotionally, the aftermath is complicated. I don’t wish to relive a pandemic, but part of me cherishes the pause – the permission to stop, the quiet, the return to essentials. I remember how nature bloomed without us, how communities rose up, how even a Zoom call warmed the heart.

The pandemic reminded me, more than ever, of life’s fragility. At the same time, we’re human: we forget, we drift back into old habits, even though the echo lives on.”

More from Ruth: ruthclaytonartist.com

facebook.com/ruthclayton.artist

instagram.com/ruthclayton.artist

Maggi Toner-Edgar, Cockermouth

Maggi is a textile artist and designer who mainly uses natural, found and repurposed materials. She is a co-director of Recreate & Make Workshop/Teaching Studio in Cockermouth and a member of The Art People, a group of five artist organisers in West Cumbria.

ORIGINAL ARTWORK: Breathe

What Maggi said at the time:

“Lockdown has been a unique time of closeness, sadness and uncertainty. I own a backyard with a few plants, and while gardening has never been a passion, I have appreciated this small breathing space and the plants – especially during a period of self-isolation in early May. Over this time, I was drawn particularly to the dandelion, with its visual similarity to the Coronavirus graphic.

Then my sister-in-law, Joan Ellis, a councillor for Cockermouth Labour Party, contracted Covid-19. She is struggling on the Covid ward, and due to underlying health conditions is now in a weakened state. This means my life will be very different when lockdown ends. The necklace – cotton thread, beads and dandelion seeds – reflects the fragility of human existence. Each of the 66 dandelion clock seeds celebrates one of Joan’s 66 years making a difference in West Cumbria. I dedicate it to Joan.”

What Maggi says now:

“Breathe was an emotional response to my situation at the time, heavily influenced by Covid: a grief-induced memoriam piece.

I spent a lot of time in my back yard during lockdown, and walking locally by the river. It was spring, and I was seeing many dandelions. Their seed heads spoke to me of breath and life’s fragility – how easily it is created and extinguished. Blowing the seeds, as I did when I was a child, brought back memories of another sad, sunny summer, many years ago, when I lost a loved one. The connection with blowing – breath – loss, and the feeling of sadness, all connected. The seeds seemed the ideal material to create a necklace, small and tight, which restricted the breath, as was happening to people with severe Covid infections. In contrast, the world was given the opportunity to breathe, industrial and polluting activity paused.

In the short term, my own character was badly affected by the pandemic. I had been outgoing and gregarious before, but became solitary and introvert.

In the short term, my own character was badly affected by the pandemic. I had been outgoing and gregarious before, but became solitary and introverted. It took a while and some effort to overcome and get back into my design business, teaching, going out and seeing friends and artists. In the longer term, the loss of my sister-in-law to the pandemic was devastating. My family struggled from the loss and spent years grieving.

I eventually got back out, and encouraged others to do so, through creativity.

One permanent effect of the pandemic came in my choice of workshop; I felt a need to be part of the community again in a real and helpful way. I formed a Community Interest Company (CIC) to ensure that people could come together physically to create. Creating online was OK, but did not have that connectivity. The CIC has added a wonderful resource to the town; we have helped teenagers connect over creative interests, and children in particular to heal through artwork and stitch.

We undervalue the arts as a means of maintaining the structure of civilised society. As a society, we value that which can be measured – money, data, qualifications – but we should not forget those things that enrich our lives in a deep and meaningful manner, which cannot easily be measured. I hope the world remembers how the arts helped the world get through a moment of insanity.”

More from Maggi: toneredgar.co.uk

Instagram: instagram.com/toneredgar

Facebook: facebook.com/RecreateMake

Mark Griffiths, Newby Head

Mark is an artist working across a range of disciplines: performance, poetry, song, photography, painting and drawing. During Covid he worked as a therapist for Cumbria County Council, with children who had experienced early life trauma. His most recent book, GRID: an outside inside journey through Cumbria, published by Caldew Press, was shortlisted for the Lakeland Book of the Year Award.

ORIGINAL ARTWORK: The Dots and the Lines

The Dots and the Lines

Children mess about on the third row;

paper bag gasps and shrieks on Pantomime Day.

The fake lion blows a phony roar through

the mouldy costume.

The clown pretends to choke, his hacking

imitating oversize feet, flapping across the sawdust

throwing up corky clouds

knees lifted high

like he’s running over hot coals.

The little girl next to me turns her head

without moving an eye.

She reveals to me what happens to

the lion at the end.

She saw the same show yesterday and grows

two feet sharing her secret knowledge.

‘All these stories end the same way’

I think to myself.

Now, months later she informs me again

from her new position.

Three inches taller, she tells me about the

clear sky and asks where the airplanes have gone.

Is there a special land they visit; maybe

they went away on holiday?

I wonder if we’ve reached the edge

of something

like a love affair that ran out of steam.

I wonder if the time we had

expired while we were busy

making lives

and taking lives

and raising children

advancing careers

buying homes

paying taxes

watching our parents

grow old and die, right there

in front of us

like a real thing.

Or perishing somewhere else, behind

closed walls

maybe on a screen, in a way

that happens only in movies

and to other people.How long have we been waiting here

caught on this drift of inattention?

A sleight of hand that caused us to miss

the last of the airplanes

bringing the survivors back home.

What Mark said then:

“When lockdown was first introduced, my artistic responses were immediate. I always tend to create quickly and revise slowly, with work that begins in one medium often ending up in another. Being unable to be with my (grown up) family has been difficult. However, continuing to work supporting children who have experienced great isolation and separation from their own families offers me perspective. ‘The Dots and the Lines’ was written after taking a walk from my Newby Head home. At a crossroads fringed by woodland and soothed by wood pigeon I noticed the absence of air contrails. The poem flowed quickly from there. It begins at a pantomime several months earlier. It ends here. In the sharp air the unwrapping of spring – that most subtle of seasons – has this year been treasured like no other.”

What Mark says now:

“The art I created for Through the Locking Glass now rests in the Museum of Anxious Anticipation. It spoke of a truth among a plethora of realities. With good grace, it may have resonated with some and offered a little comfort of a shared experience articulated.

My time during the lockdowns was spent at home in the Eden valley with my partner. We were both working for Cumbria County Council during the time, she overseeing the functioning of children’s services, working mad, exhausting hours, and I focusing on the health and wellbeing of children living in care. In between, I wrote copiously and began recording every song I had ever written and improvising new songs and poems. All of this (ongoing project) was done in single first-takes, straight to camera and posted on YouTube. It seemed like there was little time to waste on ‘perfect’ versions; ‘first-reaction shots’ were the better foil.

The pandemic both severed and offered us much, and prompted life-changing constructs and actions for many of us which, as I reflect now, are in the main distinguished by their polarities… a distilled, new sense of priorities; a reminder of the unemphatic realities of being and non-being; of loss, absence, longing and regret; of planning for the future and of forgetting… kindness and selfishness… renewed hope and adherence to a sense of nationhood and a scornful mistrust and anger in our systems and leadership… a curt elucidation of the inequalities of the way we have acceded our lives and livelihoods.

The lives we most desire constitute simple elements:

Family. Friendships. Companionship. A tender reciprocity. Good health.

A sense of comfort and safety. An opportunity to feel useful.

Easy pleasures and occasional madnesses…

… we retired or changed jobs, moved, spent more time with loved ones/drank more/drank less/partied/discovered nature/discovered ourselves/ignored the rules/followed the rules/lived for ourselves or the contrary/identified and joined new world-views/became impounded by a realisation we were almost completely bound in our lives and the economics that fettered us.

I miss the clear air and the quietness in the sky.

I do not miss the distance of the glass between us.

I wrote much during those times and continue to reference, or be subject to an imprint of, those years, despite the collective forgetting, like a ‘disappeared person’ lost in the gulags, South American graves or Trump’s developing new/old idea.

But that’s another story to tell the grandkids.”

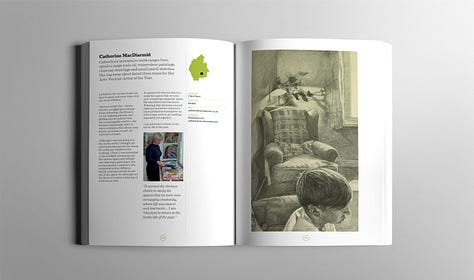

Debbie Copley, Kendal

Debbie is a stained-glass artist who works out of her studio on Allhallows Lane, Kendal.

ORIGINAL ARTWORK: Through the think in’ glass

What Debbie said at the time:

“At first, when it all became black and white (the rules, that is) on the evening of the 23rd, I guess I was a little scared. But prepared… An ample larder and the motivation to do much-needed tasks around the house kept me ‘locked in’. I ventured out eventually to find the world a different place: near-deserted streets with folks crossing over; shops with chevrons and cordons and screens. I soon learned the rules of this new planet, and my life adjusted to suit them. A simple routine of existence evolved, revolving around the sun, spinning out time as far as I could stretch it. I read. I drew. I cooked. I ran. I yoga’d… I became expert at filling the hours in my day. Reading in my sun spot became my luxury, with its view of big sky, rooftops and chimneys, welcome swifts and the Town Hall clock. As I read more, I drew more, relaxed more and made notes. This golden time has been something of a gift – a time to recharge batteries. I wonder what will become my new normal going forwards.”

What Debbie says now:

“The art I created for Through the Locking Glass reminds me today that I believe in what I do. It spoke my truth. My take. We all made adjustments; took certain steps, assumed a certain stance. We all interpret news and outcomes in different ways. I think I accept a truth I am comfortable with, and trust myself to act accordingly.

I look at my pandemic panels [‘Through the think in’ glass’ is one of three] and am pleased with what I see. I display them in my workshop window alongside other commissions. Folk stop and come in to tell me how they brighten their day. Art and light. Beautiful things and stopping and staring. Giving thanks. All are important to society.

I spent lockdown at home in Kendal or in my studio, feeling fortunate to be living, walking and running in beautiful surroundings. I am grateful for that time and for government grants which enabled me to invest in my business and myself: a new kiln inspired me to explore my subject and push to be the best stained-glass artist I could be.

The pandemic coincided with a time when I was undergoing change. I was at an age and situation when evaluating what was important to me came with a certain wisdom and experience. I learnt that every day is a learning day. It made me better at my life and my job.

Covid influenced everyone differently. Maybe creatives reacted differently again; creative brains can perhaps process – make sense of a new or unusual situation, find a way to express and release emotions or frustrations.

I value my health and that of those around me, but worry about the impact of those strange circumstances on younger generations. I appreciate life’s preciousness, and the art and beautiful things that are vital in making society a better place.

I do not miss any aspect of the pandemic. I look back and think, ‘Did it really happen?’ Nostalgic for that? I don't think so.

I do not miss any aspect of the pandemic. I look back and think, ‘Did it really happen?’ The absurdity of queuing with healthy people to be vaccinated by uniformed soldiers, of death rates on the news. Nostalgic for that? I don't think so.”

Dr Dave Camlin, West Cumbria

Dave is a singer, songwriter and choir leader who, during lockdown, brought voices from around the county together via Zoom.

ORIGINAL ARTWORK: The Great Divide

What Dave said then:

“Lockdown disrupted everything: no live performances; freelance gigs cancelled; all teaching moved online; and I was no longer able to run my community choirs face-to-face. On the flip side, the challenges of lockdown have been just another constraint that have helped drive my creativity. I moved the choirs I lead onto Zoom. We meet virtually each week to learn new songs, sing old favourites and connect. We’re also recording an album, with choir members recording themselves at home and sending me their contributions, which I edit together. One of the songs we’re including is a new one I’ve co-written with choir members about lockdown, ‘The Great Divide’.

“We’re keeping two metres between us,

Whenever we leave our front door.

We can’t congregate with our neighbours, in case we’d be breakin’ the law,

We can’t travel unless it’s essential, so we don’t leave the house any more, but...

We can still sing across the great divide...”

What Dave says now:

“I’m proud of the artwork created during lockdown as a record of the resilience we found as a singing community, even though it was of its time and no-one would wish to go back there. Making a ‘virtual choir’ piece like ‘The Great Divide’ represented a huge amount of unpaid work, but it was worth it to know that it was helping people feel connected to their analogue social networks. The words of the song, “we can still sing across the great divide” felt like a mild act of resistance, when group singing was scapegoated in the pandemic’s early stages as potential super-spreader events.

In many ways, lockdown was a blessing for me and my wife Angie. We live remotely, but near enough to cycle to many lakes for exercise. That summer, we had the western Lakes to ourselves, enjoying the immersive soundscapes of the natural environment in a world without human noise – just the natural world in all her glory.

Of course, there were horrible bits as well, in particular my elderly dad getting discharged from hospital to live with us, infected with the virus, newly (and falsely) diagnosed with cancer, recovering from a collapsed lung, and confused. He lived in one part of the house, I in another and Angie in another, in an attempt to keep us all from getting infected. They were bonkers times, getting decked out in full PPE to take my dad his meals – bless him, he had no idea what was going on. He died in 2021 at the tail end of the final lockdown, his time with us possibly the hardest four months I’ve lived through. But I’m proud to have been able to look after him during his final months; it opened my eyes to the numbers of dedicated people caring for their loved ones. It’s a hard road, but also a pure gift of love.

Since the pandemic, my art has moved along more ecological lines, highlighting the complex ways in which we relate to the natural world, and the destructive impact humans continue to have on the earth’s systems. It’s become clear that our species could disappear and those systems will simply recover; we’re insignificant in the larger scheme of things.

What emerged for me was a clear sense that national governments don’t hold the keys to the future: there’s only us.

The pandemic provided a useful stimulus: we need to radically change our behaviour if we are to avoid climate change’s worst outcomes, and that urgency just gets stronger. I’m more hopeful, because what emerged for me was a clear sense that national governments don’t hold the keys to the future: there’s only us. I’m trying to amplify that message through the book I wrote after the pandemic, Music Making and Civic Imagination, and in our new Cumberlandia festival, strengthening our community in the face of global precarity.

I wouldn’t wish to return to those days but I’m proud that, in adversity, the instinct to create is what helped me through.”

More from Dave: www.davecamlin.com

www.davecamlin.com/lakes-meditations

Christine Hurford, Penrith

Christine’s work responds to place and time, linking ancient places, customs, lives and beliefs with contemporary times. She has had large installations shown around the north of England.

ORIGINAL ARTWORK: Leaves That Fell in the Spring, 2020

What Christine said then:

“As with everyone, my world has shrunk to a circle around the house of 2–3 miles radius. The woods and quarries near Penrith are quiet except for the birds and a few people. Many of the old quarries have been left and are overgrown; lonely places where once there was the noise of reddish soft-stone being removed to build much of Penrith and its environs. Our house is opposite one such quarry.

I started to make porcelain leaves – very thin and fragile – of oak, birch, beech, ash and hawthorn. They were then given a black edge, as were the memorial cards of years ago, sent out when someone died. I have several for great-grandparents and great aunts and uncles.

‘Leaves that fell in the spring, 2020’ was in situ for just one brief hour in the Bowscar quarry woods – a long leaf shape made from around 400 smaller leaves. They are conifer woodlands so my leaves of native trees should not have been there, but fragile – whole or broken – they were there. It was a quiet, private exhibition – just me sitting quietly and then photographing them.”

What Christine says now:

“The title of my work was chosen for the deaths that occurred so quickly at the start of the pandemic. Leaves would normally fall in the autumn, not spring – an unnatural occurrence. Two friends, full of life even in their 70s, died in the first few days. The shock made me think and start to make the work.

The repetitive making and firing of hundreds of delicate leaves certainly helped me during that time. The piece was seen by few people – no audience unless they happened to be passing. It was almost private.

Lockdowns were spent at home in Penrith, the first with my husband David. He died (not with Covid) just before the second lockdown, so funeral numbers were restricted, with spaced seating arrangements and no gathering afterwards. The other lockdowns were spent on my own. I only managed with the help and companionship of friends.

Retrospectively, I cannot separate the pandemic from David’s death. My mental health was changed by my husband’s death, not, I think, the pandemic, and it was a bumpy ride. I later found it difficult to be motivated and think about art; even now I struggle to keep my mind on work. I am in my 70s and do not need to continue, though I want to.

The need for gatherings of friends has, in a way, made for stronger friendships. I like to go off on my own for days to sketch; this is a solace, but I return needing companionship.

Everyone had difficult times, but I had the advantage of being able to respond and create. Many found the time dragged and some found they had little to do; I was always busy and am grateful for that.

The pandemic seemed to pass quietly, drifting away until now it is rarely mentioned other than in occasional chats about the weirdness of the time. I miss the peace that descended, the slower pace.

We forget so much, blotted out.”

From from Christine: chrishurford.co.uk

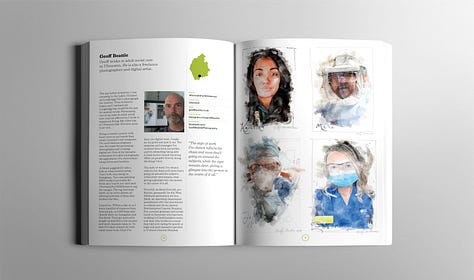

Geoff Beattie, Ulverston

Geoff is a freelance photographer and digital artist who at the time of the pandemic worked in adult social care in Ulverston.

ORIGINAL PIECE: #PortraitsForNHSHeroes

What Geoff said then:

“The day before lockdown I was camping in the Lakes. I’d hiked up Loughrigg Fell to photograph the sunrise. Then lockdown began and I realised my Loughrigg trip would be the last for several weeks. Being a creative person with more time on my hands than usual, I turned to my computer. I’ve used various programs over the years for processing photographs and creating digital art.

A friend suggested I take a look at what another artist, Tom Croft, was doing on Instagram. Tom was painting NHS worker’s portraits for them as a ‘thank you’ and used #PortraitsForNHSHeroes to tag the images. The tag was soon taken up by other artists, all offering portraits of front-line workers for free. I joined in. Within a day or so I had a handful of requests from local people, so I did those and shared them on Instagram and Facebook. They got noticed by people up and down the country and more requests came in. The response and messages I’ve received have been incredible, and it’s rewarding being able to have such a morale-boosting effect on people’s lives by doing the thing I love.

The style of work I’ve chosen reflects the chaos and mess that’s going on around the subjects, while their eyes remain clear, giving a glimpse into the person at the centre of it all.”

What Geoff says now:

“The pandemic was the wake up call I hadn't known I needed. I’ve met others for whom it had the same effect – creative people tend to be more sensitive to what’s going on in the world.

My mental health took a dive initially, but I emerged with a new outlook and a better perspective. Once everything calmed down, I bought a campervan, had a six-week trip around Scotland in the autumn of 2021, and got the van life bug.

In December, 2022, my landlady asked me to leave because I wasn’t going to have the jab and she didn't feel safe. I'd had plenty of jabs over the years, but something about the Covid vaccinations didn't seem right. I was also being pressured to have it at work – I was a care assistant in supported living – which resulted in my doctor signing me off with stress. This all made for a difficult time, but I suddenly had the opportunity to step back and see the bigger picture. So, on April 1, 2022, I moved into my van and spent six months driving around Britain’s coastline. I returned to Ulverston and Day Services for about six months before leaving for Italy to house-sit for a friend. Then I backpacked around India for six months. That was a profound, life-changing trip – even aged 53 – and in December, 2024 I flew back to India on a one-way ticket. I travelled around and at the end of March flew to Tbilisi, Georgia, where I remain.

Covid pushed me out of my 9–5 comfort zone, woke me up to government corruption and the conditioning of our society, and inspired me to live an alternative life, rekindling my love of travel.

Covid pushed me out of my 9–5 comfort zone, woke me up to government corruption and the conditioning of our society, and inspired me to live an alternative life, rekindling my love of travel. I still do some photography, but have started to write about the traps we fall into: the 9–5 life, consumerism, and the way we are unconsciously conditioned by society and government.

I did enjoy lockdown’s quiet and peacefulness, but I don’t miss it. My life has evolved, my creativity has taken a new direction. The art I made then feels like it was created by a different person.

I still regard Ulverston as home, though home now tends to be wherever I am. Since moving into the van, I enjoy a minimalist lifestyle and travel with an 8kg backpack, small enough to take as carry-on baggage. Honestly, that’s all I need.”

There are still a handful of copies of Through the Locking Glass available (£9.90) from inspiredbylakeland.co.uk/collections/books/products/through-the-locking-glass

What a great piece. Thanks, John.

A fascinating read. I wonder how many of us have reflected on our time in lockdown from a distance like this?