Maps of Cumbria #56: 'Plan of Line of Aqueduct from Thirlmere to Manchester', Manchester Corporation Water Works

In this excerpt from the forthcoming book 'Cumbria – 1,000 years of maps', the forces of industrial progress and landscape preservation wage war over the crystal-clear waters of Thirlmere

On 13 October, 1894 Alderman Sir John James Harwood, Chairman of the Manchester Corporation Water Works committee, stood before the assembled crowd in Albert Square, Manchester and turned the taps on a specially erected fountain. Moments later onlookers jostled for their first taste of Lakeland water. The ceremony celebrated an audacious feat of Victorian engineering and marked the end point in a protracted struggle between industrial muscle and natural beauty that fanned the flames of a nascent conservation movement.

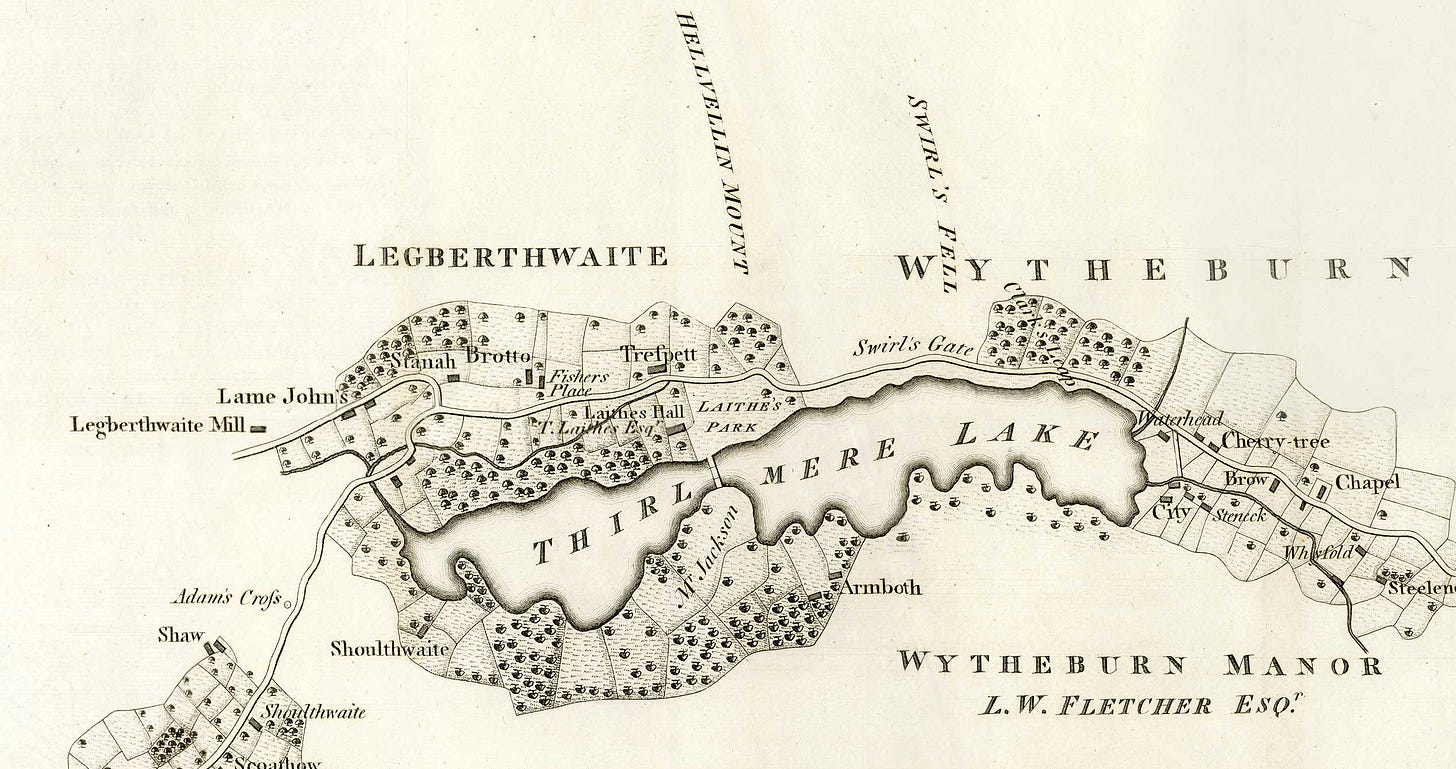

Long before water flowed into Albert Square, Donald’s 1774 map of Cumberland shows Thurle Meer as two lakes strung along the valley below Helvellyn – the hamlet of Wythburn at its south end and Armboth to the west. Nearly a century later the First Edition Six-inch Ordnance Survey, published in 1867, still shows Thirlmere as two lakes meeting at a narrow waist spanned by ‘Wath Bridge’. But by this date the dice were loaded; the cogs of history were moving, and municipal authorities were already eyeing the lake in this isolated northern vale.

The waters of Thorle Meer were originally considered for London in 1863. But that suggestion was dismissed as prohibitively expensive; chalk aquifers and the Thames were chosen to supply the capital’s water instead. Nearer to home, an 81-day drought in 1868 focused minds in the booming – and ever-thirsty – cotton town of Manchester. The Longdendale chain of reservoirs in Derbyshire could not satisfy demand, and, concerned for sanitation in the rapidly growing town (the Manchester cholera outbreak of 1832 was within living memory, and London experienced a major epidemic in 1866), medical officer Dr Talham wrote to council officials: “If you supply me with an unlimited supply of good and pure water, I will be responsible for the health of the city.” Surveyors were duly despatched in search of the good and the pure.

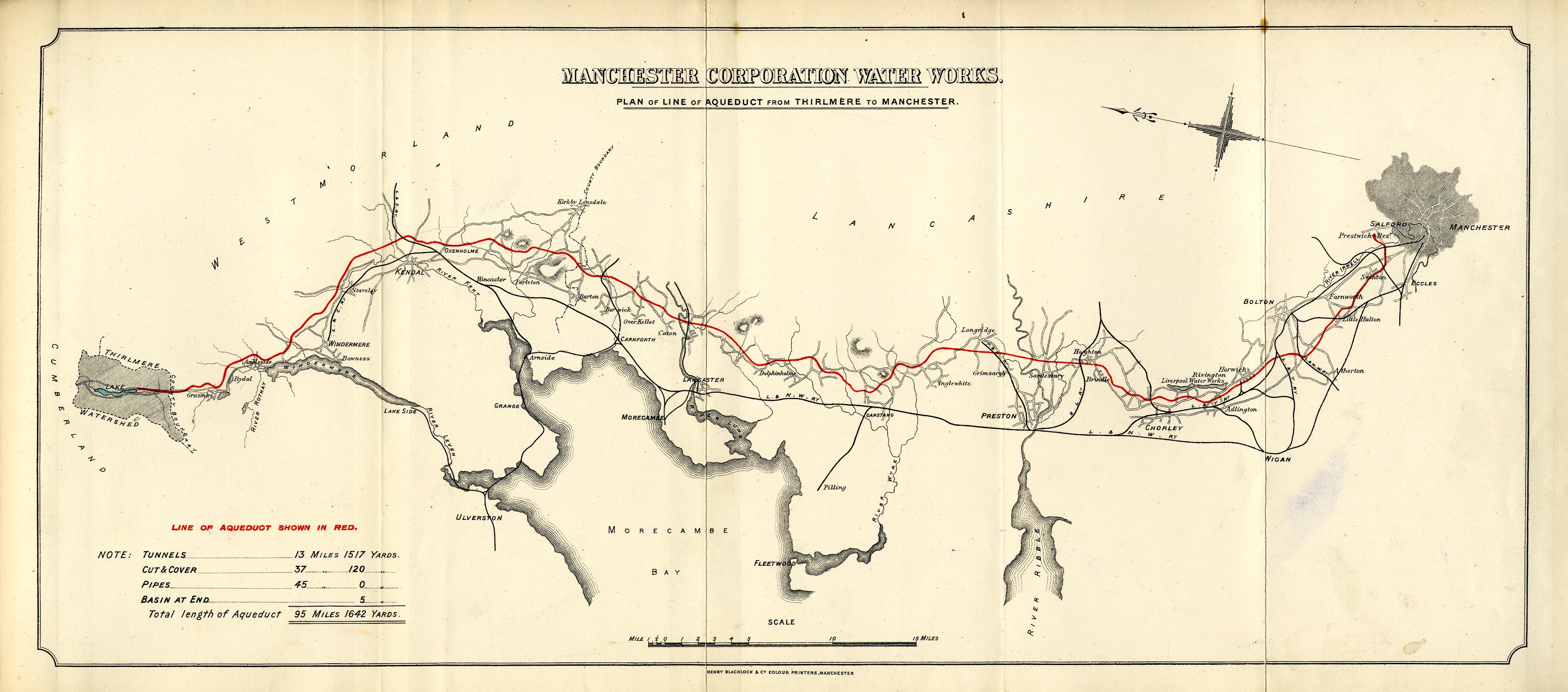

Eight years later, John Fredrick Bateman, chief engineer to Manchester Corporation (MC), penned a note to Alderman Harwood: “It appears on full consideration, that Thirlmere deserves your special attention as an independent source of supply to Manchester and I therefore recommend its adoption.” The town had found its ‘unlimited supply’, and in 1877 MC made its intentions public, seeking parliamentary powers to block the outflow of the lake, construct an 800-foot-long dam and build a 95-mile aqueduct to transport Lakeland water to Manchester. Compulsory purchase powers were sought to acquire land in the valley bottom and in much of the wider catchment.

The choice of Thirlmere was no foregone conclusion. Haweswater and Ullswater were also considered, but Thirlmere received more rainfall, was deemed a purer supply, and – crucially – was set at a higher elevation, which meant water could travel south entirely by gravity.

Manchester did not get Cumberland water without a fight; in September 1877 the Thirlmere Defence Association (TDA) was formed comprising artists, poets and campaigning luminaries including Derwent Coleridge (son of Samuel Taylor), Thomas Carlyle and William Morris. The flooding of a much-loved valley would not only displace two communities and flood 463 acres of farmland, they argued, it would also – in the words of an editorial in The Times – destroy “one of the [country’s] fairest spots… It may be said the whole world has an interest in keeping it in its primitive state.”

The energetic defence of the “sort of national property” that Wordsworth had conceived in his Guide to the Lakes (1810) came, in the end, to nothing. The efforts of the TDA – including presenting to committee members a foul-smelling sludge, which it was claimed would form the shoreline of the new reservoir – failed, and the Thirlmere Bill received Royal Assent in May 1879.

Alderman Harwood laid the dam’s foundation stone in August 1890. Engineering work was initially overseen by John Frederick La Trobe Bateman (1810–89), architect of the Longdendale chain with the epithet ‘greatest dam-builder of his generation’. The first phase of work raised the dam at the north end of the lake, initially increasing its level by 20 feet. Meanwhile, a second team of navvies began blasting into bedrock below Dunmail Raise. Over the next 37 years, three more pipes were added and the reservoir raised to 50 feet above its original level (a subsequent final rise increased it to around 54 feet).

Today, nearly 130 years since water first flowed into Albert Square, Thirlmere despatches between 40 and 50 million litres of drinking water a day, not only to millions of families in the north-west, but also – following construction of a new pipeline that exits north from the reservoir – 80,000 households on the Cumbrian coast.

The TDA’s loss, meanwhile, was not in vain. Despondent at the flooding of the valley, and fighting a constant battle in subsequent years against road builders and railway speculators, the Keswick campaigning canon Hardwicke Rawnsley wrote to the Evening Standard in 1893: “Each year these public grounds of recreation and health are narrowed and invaded by private greed, miscalled enterprise.” To protect these ‘public grounds’ for the nation, in January 1895 Rawnsley joined with Octavia Hill and Robert Hunter to establish the National Trust. It now owns and cares for more than 20 per cent of the Lake District National Park… its lineage directly traceable to a flooded valley with ‘unlimited’ water.

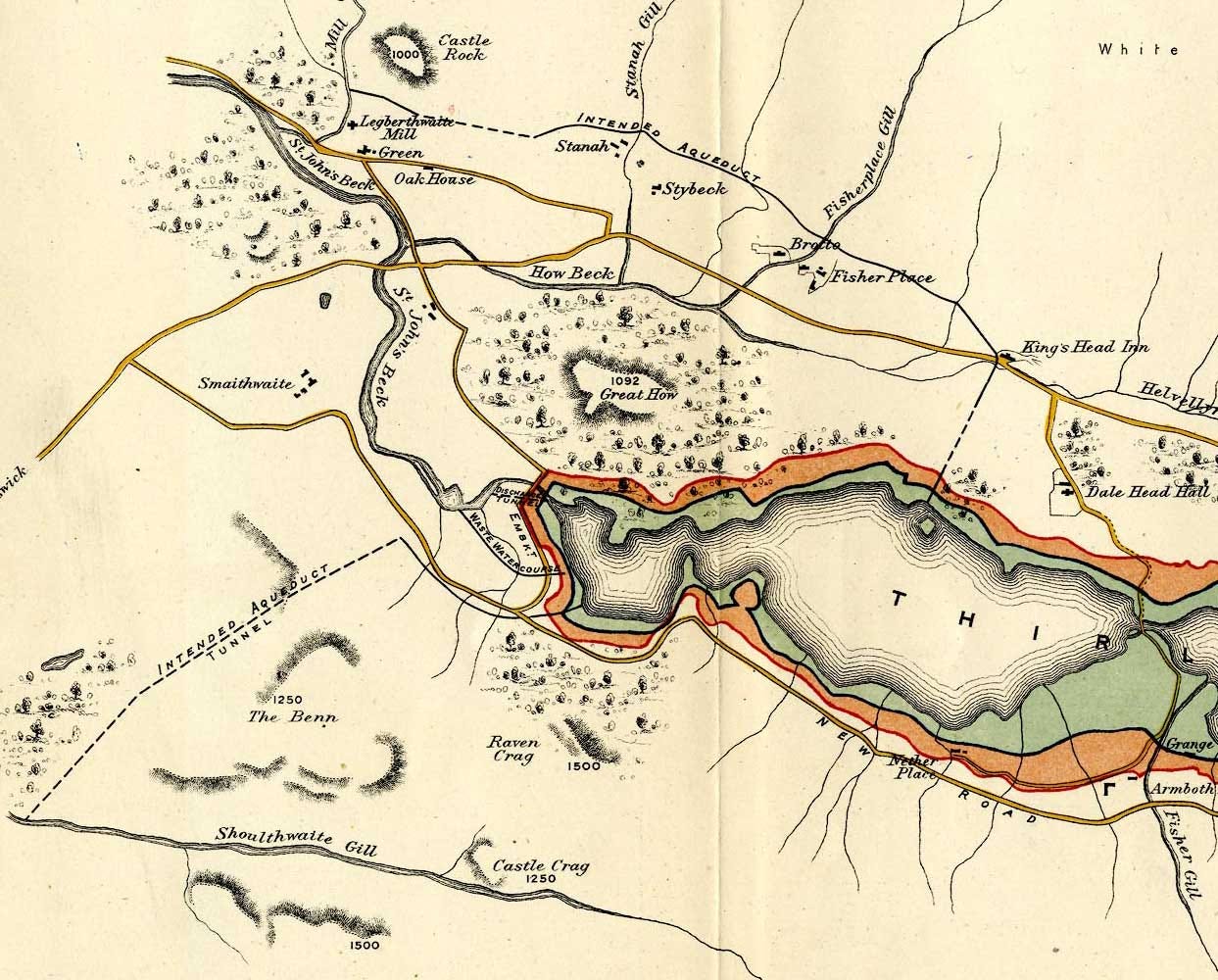

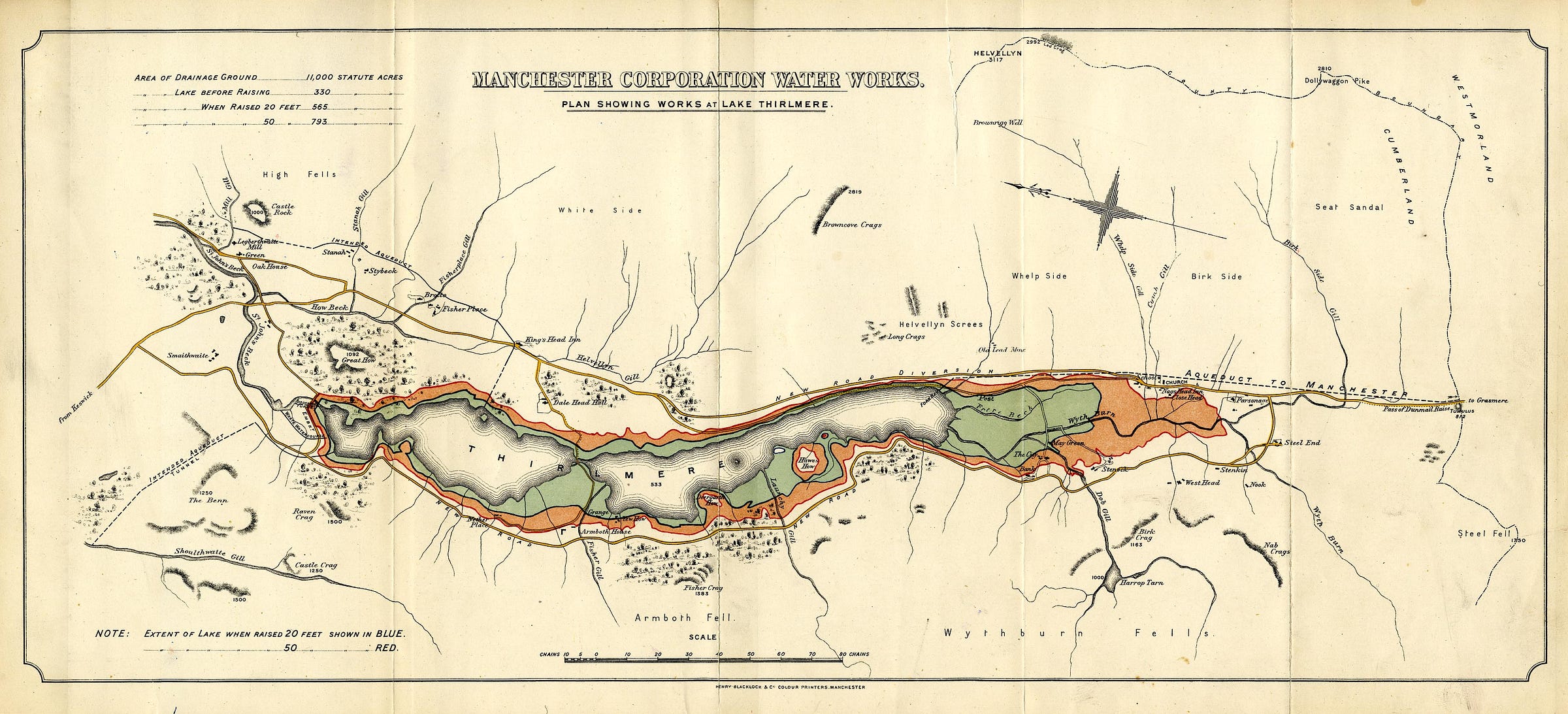

The above map, at the scale of about three inches to the mile and with north located left, shows the planned reservoir in greater detail, and the effect of raising the lake level initially by 20 feet (‘blue’ according to the key) and then 50 feet (‘red’) when the fourth and final pipeline was completed. The settlement of Armboth is lost beneath the waters, together with much of Wythburn. The line of the ‘Aqueduct to Manchester’ is shown, heading south from the outlet at Fore Bay for Dunmail Raise.

A note, top left, reports the original size of the lake to be 330 statute acres. Raising its level to 20 feet (in 1890) increased that to 565 acres, and raising it again to 50 increased it to 793 acres – though this last increase did not take place until 1927, 32 years after the map was made.

To maximise water capture in the catchment, the map indicates two ‘intended aqueducts’ (indicated as dashed lines). The first diverts the outflows of Mill Gill, Stanah Gill and Fisherplace Gill from St John’s Beck into Thirlmere. Note that the actual route of this aqueduct was ultimately changed – extending south to enter the reservoir much closer to the modern car park at Swirls (unmarked).

The second intended aqueduct, from Shoulthwaite Gill, was never built – enough rain reached the reservoir without it – although there is evidence of a crumbling test weir, marked on OS maps, spanning the gill below Goat Crag.

The above text and maps are taken from the book Cumbria – 1,000 years of maps from Inspired by Lakeland, featuring more than 100 charts, surveys and maps from ten centuries of cartography. For more see here.

The maps are provided courtesy of The Armitt Trust, reproduced by permission of Jean Norgate.