Cockley Beck: 'Anything for a quiet life'

The name John Pepper is largely lost in Lakeland literary circles. But his ode to Cockley Beck, where he spent six winters engaged in a search for meaning, is a classic of nature writing.

Words by George Kitching.

When the author John Pepper died in 2017 at the age of 75, his passing merited a brief mention in The Guardian, but his name meant little to most. “His writing never brought him fame”, notes the obituary.

But it did have influence. Robert Macfarlane listed Cockley Beck: A Celebration of Lakeland in Winter (1984) as “one of the great classics of British nature writing”. Indeed Macfarlane’s list ranked Pepper alongside luminaries such as Ted Hughes, Norman Nicholson and Dorothy Wordsworth. Cockley Beck also won a Northern Arts literary award.

Pepper was born in Doncaster in 1942. His family later moved to Southampton, where he went to school, leaving aged 16 to train as a reporter and attend art college. In his early 20s, following a spell at the East London News Agency, he relocated to Bristol where he moved into television, fronting a nightly news programme and making documentaries.

In 1972 – then aged 30, and a year before his brief marriage to Wendy Godwin ended in divorce – Pepper embarked on a quest for meaning that saw him travel widely through the USA, Spain and Wales. Eventually, it led him to a spartan cottage in Lakeland’s Duddon Valley.

In Cockley Beck, Pepper recalls his arrival in this remote western dale:

“I had stumbled on the valley one winter by accident… There was so much beauty, such peace. Peaks rose into the stars like psalms. Yet they seemed to be human too, and even friends.

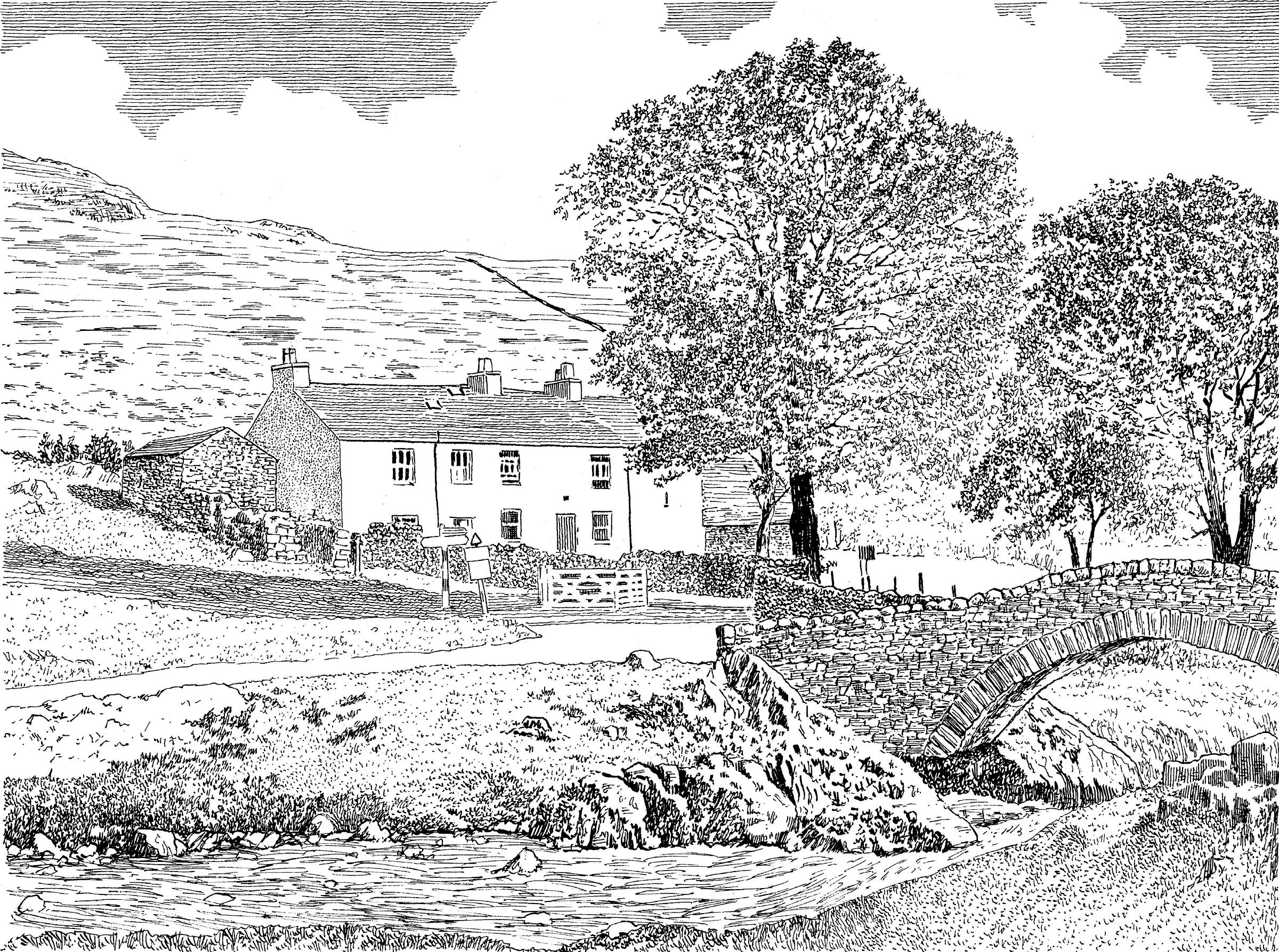

So I came upon a little stone cottage that had once been a woodshed. It was tacked onto a lone crossroads farm at the head of the vale, in a moonscape. The front 'garden' was a silhouette of trees, interlopers, beside a waterfall, with Scafell, England's highest summit, behind… Altogether, for my money, Lakeland at its best – without the daffodils.”

That lone crossroads farm was Cockley Beck – a whitewashed building besides the road bridge that gives access between Wrynose and Hardknott passes. The tenant farmer thought Pepper mad for renting the cottage out of season, but the writer did so for six successive winters, returning to London each spring. The experience yielded a book that is exquisitely lyrical, deeply insightful, and bears a message that has become ever more relevant in an age of 24/7 culture and instant everything.

At its heart Cockley Beck is a paean to silence as an antidote to the dehumanising effects of consumerism, which, with its incessant clamour, robs us of the opportunity to truly know ourselves. Writes Pepper:

“‘Anything for a quiet life’, we sighed, and filled it with noise.

The racket we engineered to escape from ourselves was more, too, than the relentless product of transistors, hi-fis, TVs, videos, one-arm bandits, space invaders, pubs, parties, theatres, musical events, football matches and all the other forms of popular entertainment. It was the shrieking of newspaper headlines and advertisement hoardings, high fashion, low fashion, modern architecture, paperback jackets and political panaceas.

It was the buzz we got from alcohol, drugs, coffee, tea and flattery; from gurus and meditation. The excitement of screaming at one's wife, of gossip, and watching our cities in flames. The sound of our wheels and wings speeding us from nowhere to nowhere but sparing us the exigencies of having to be somewhere. It was the garbled silences administered by Valium. The graffiti over our walls, the two fingers everywhere thrust in the air.

A man on the top of Scafell, plugged into ‘The Archers’.”

For Pepper, the key to fulfilment is to shut out the noise and become content in the simple act of existing; to – in the parlance of our own age – live in the moment. It is a raven that shows him the way:

“He was up there for the hell of it; the celebration and the ecstasy... A great bird with nothing to fear; in all the world a ledge, the next meal, and the midnight star its home. When I could join it up there in the high crags and read its glad cry, ‘This is all there is,’ and fly with him in the unlimited reaches of my mind, would there ever be need of more?

The task though: to fly beyond imagination, and into life...”

If Pepper’s winters at Cockley Beck allow a form of renewal, the first few days of each trip are not easy. There is something of the drug user’s withdrawal as he settles again into the quiet life:

“The sheer isolation of the dalehead always took the breath away, made me hurt somewhat for a regular job, wife and family, a warm home and all the other things one had begun to weary of and cut away like dead wood.”

The key, he finds, is to slow down and open himself to the place:

“I used to get out my blankets and candle, and sit. Sit for an hour, listening to the dawn come up with the birds, letting the new day arrive in its own good time, feeling its way like the tide.”

Crucially, Pepper does not simply want to escape the world. Cockley Beck, instead, becomes a catalyst for finding a way to live more contentedly in society:

“I couldn't make my peace with Nature if I remained at war with everything else I had ‘abandoned’… The only point in learning how to live alone was to be able to live all the better with others.”

There is irony in the fact that Pepper’s reintegration into society happens in one of Lakeland’s loneliest dales – his nearest neighbours located two miles away.

But community is both found and embraced in the ‘merry neets’ hosted by a neighbour and fuelled by home-brewed ale, the after-effects of which have Pepper “wishing fervently for euthanasia”. It is there in Christmas festivities at the Newfield Inn, where the most taciturn of farmers moves his audience to tears with achingly sweet renditions of old songs. It is personified in the valley’s three postmen who deliver more than letters: they come to Cockley Beck with shopping and messages; they make phone calls when telephone lines are down; they chop wood and help with lambing. It is manifest in how valley folk pull together to rescue sheep and clear snow during the winter of 1981/82, which brought one of the worst blizzards ever recorded to the Lakes.

“Caring…” he reflects, “you just found a little bit more of it left up in the hills…”

The many characters that people Cockley Beck embody dogged self-reliance and neighbourly compassion. They seem, also, to share a sense of contentment borne of wanting little more than they already have.

The reader is introduced, for example, to Ian Davidson, a former classics teacher and shop steward, now a forester and poet, who tells Pepper that life in the valley is like “being all together in a boat... The hills hold you…”

Farmer’s wife Barbara Temple, meanwhile, reveals that she holidays without her husband because “he simply got ill when he strayed from the hills too long”; while in a whisky-warmed conversation, Norman Nicholson – the Lakeland Poet Laureate – tells Pepper how the people he grew up around do not think of him as a “Writer (capital W). I happen to be ‘Joe Nicholson’s son who’s happened to take up writing.’ And I like that.”

As the book nears its conclusion, Pepper comes to realise that his annual pilgrimage to Dunnerdale must soon end. To tarry at Cockley Beck indefinitely risks arresting the author’s quest for personal growth and – ultimately – love. After six years, he concedes it is time to leave:

“From such peace and grandeur – a vestigial sadness. An intuition that my hill winters might now, for a while at least, be drawing to their close. For if in this apprenticeship in solitude a few preliminary answers to the purpose of waking each morning had been granted me, and I had had the good fortune as a result to know many moments of great beauty, coming at the last, I hoped, to spy if yet by no means always act love’s meaning, solitude itself now threatened further progress.”

In a lyrical closing passage he quotes T. S. Eliot: “And the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time”.

love the artwork and the tale

I have the cover image, used on the book, on my wall … taken by the wonderful photographer David Briggs! It is a long time since I’ve seen his work …

Must find a copy of John Peppers book! Fond memories of this area …