Hefted #3: Sept 2024 - 'It’ll niver catch on'

Despatches from Cumbria and the Lake District: A 1950s Threlkeld childhood – Walking the South Tyne valley – Long distance walks through Cumbria – Fairies of Eskdale & more...

Welcome to the third edition of Hefted, a monthly newsletter from Mark Richards and Dave Felton at Countrystride featuring a range of bite-sized news, views and long reads centred on the landscapes, people and heritage of Cumbria and the Lakes.

This month, our Long Read recalls a 1950s Threlkeld childhood; Mark explores the understated upper South Tyne valley; Alan Cleaver seeks out the ‘ancient little folk’ of Eskdale; Dave picks his five favourite long distance walks that spend time in Cumbria; and our Postcard from the Past comes from a pre-war Grange-over-Sands.

The gather: Pick of the Cumbrian headlines

Plans to restore a lost area of Atlantic rainforest have been announced as part of a new 3,000-acre nature reserve on the Skiddaw massif. Skiddaw House, along with 1,214 hectares of land, including the summits of Skiddaw, Great Calva and Little Calva, were put up for sale with a guide price of £10 million in November 2022. Now Cumbria Wildlife Trust (CWT) has announced it is close to acquiring the property, minus the House itself. “The purchase of Skiddaw Forest presents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to put nature into recovery in our uplands,” noted the Trust, outlining a 100-year plan to restore “an area of true wilderness where nature thrives and people can become lost in the natural world.” The charity is fundraising to secure the property.

A new car park with space for 70 cars and six coaches has been approved for the centre of Coniston. Two previous planning applications for the car park, to be built on land owned by Coppermines Lakes Cottages businessman Phil Johnston, had been turned down by the Lake District National Park Authority. More from the BBC.

Dirty beaches, or dirty data? A bit of both, perhaps, as a beach in Cumbria was named the UK’s dirtiest. Haverigg Beach, at the mouth of the Duddon, was found to have high levels of E. coli bacteria and Intestinal Enterococci in a study conducted by JournaData. The beach was awarded a “water cleanliness score” of just 2.16 out of ten, slightly lower than Southend Westcliff Bay at 2.76. Cue local disappointment / outrage. But after the research company acknowledged no independent testing of the water had been carried out, The Westmorland Gazette interrogated the methodology used – and found it lacking.

There was no data lacking during another week-long untreated sewage discharge into Windermere by United Utilities (UU). Storm overflows at Near Sawrey and Hawkshead Pumping Station began pumping raw sewage into watercourses destined for England’s largest lake on Thursday 22 August, and did not stop for seven days. UU blamed “heavy rainfall, like that seen in the Lake District over recent days”. Save Windermere campaigner Matt Staniek said: "Storm overflows are only supposed to occur in exceptional circumstances. Something like Storm Desmond is exceptional. We've simply had a wet summer in the Lake District.” More from the BBC.

Are pharmaceuticals in the water a new threat to Lakeland rivers? A report on the state of rivers in England’s national parks – including the Lake District – has revealed widespread contamination from pharmaceuticals. Hefted delved into the Lakeland data.

A runner has died while undertaking the Bob Graham Round. Support runners for the man called Mountain Rescue when their friend fell into Pillar Cove while descending from Pillar to Kirk Fell. More from Cumbria Crack.

Oops! Staff at Tullie (formerly Tullie House Museum), in Carlisle, have taken to social media to acknowledge a typo in a major new advertising campaign. “Yep, we've spotted the typos. Why is it that they’re so easy to miss until you’ve had them printed on huge banners?”, they wrote of the ‘We are Carlise’ banners. More on X. (And more about the museum’s latest exhibition – centred on Carlisle United’s history – can be found here.)

There are still tickets left for our Countrystride late summer gathering at Force Café, Ambleside on 19 September. Come and join Mark and Dave for an evening of convivial talks and good food as we hear from photographer Tom McNally on ‘What lies beneath: Lost mines of the Lake District’ and author, adventurer and Long Distance Walkers Association president Phoebe Smith on Love, loss and life on Britain’s ancient paths. More from Countrystride.

Two months after members of the Lakes Parish Council passed a motion of no confidence in the Lake District National Park Authority, north of The Raise, councillors from Borrowdale Parish Council (PC) are writing to the Park voicing its own concerns over tourist pressure in the area. “There has been too much emphasis on encouraging more visitors before a solution has been found to the problems they cause (car parking, toilets, etc),” notes the letter. “Borrowdale PC do not accept the claim, that many applications for holiday accommodation make, that ‘they will help the local economy’… the description ‘Adventure Capital’ has not been helpful and should be dropped.” More from Borrowdale Parish Council.

Emergency teams were called to Wasdale after campers got into a row. Volunteers from Wasdale Mountain Rescue, alongside colleagues from Cumbria Police, the Coastguard, Maritime and Coastguard Agency Rescue 936 and Cumbria Fire and Rescue Service arrived at Wast Water following reports of screams coming from the lake. They turned out to be raised voices following a lakeside argument. More from Cumbria Crack.

Will it ever stop raining? Storm Lilian caused disruption to rail services across the county, with flooding blocking the coast line between Workington and Whitehaven. Meanwhile a landslip below Newlands Hause closed the road to Buttermere, Solfest – the music and arts festival on the north Cumbria coast – rearranged its 20th anniversary programme to avoid the worst of the weather, and The Keswick Show, a feature of the agricultural calendar for more than 150 years, cancelled its Bank Holiday event. Meanwhile, a report compiled by Starling Roost Weather found that parts of Cumbria (Honister – 904.4mm; Seathwaite Farm – 745.8mm; Brotherswater – 483.9mm) experienced August rainfall many times greater than the national average of 82.4mm. More from the Westmorland Gazette.

Villagers in Hesket Newmarket are fundraising to save their shop. With the store’s current owner retiring, the Hesket Newmarket Community Shop project has raised £210,000 of a £250,000 target. The village pub, The Old Crown, is already in community hands. More from the BBC.

A Carlisle man has denied, for the second time, felling the tree at Sycamore Gap. Daniel Graham, 38, is one of two men accused of toppling one of Britain’s favourite trees. More from the Independent.

Closed since September 2021, the footpath that accesses ‘Ruskin’s View’ in Kirkby Lonsdale has re-opened. Victorian polymath John Ruskin famously wrote that the view from The Brow over the River Lune was “one of the loveliest views in England, therefore in the world”. More from The Westmorland Gazette.

…Also in Kirkby, our friend Matt Sowerby (Countrystride #50) has confirmed the return of the Kirkby Lonsdale Poetry Festival, running September 13–15, “with a vibrant programme of performances, open mics, workshops, theatre and typewriter busking – all with the stunning backdrop of the Yorkshire Dales.” More details, including the line-up, is on Facebook.

The Normal Nicholson Society has secured funding to turn the Millom poet’s former home into a visitor attraction. The £64,000 grant will help the Society create a coffee shop, events space and tourist accommodation at 14 St George’s Terrace. More from the BBC. You can hear our podcast about the poet at countrystride.co.uk/single-post/countrystride-61-norman-nicholson

A “big cat and cub” has been spotted in the Cumbrian countryside. The news – reported on a dedicated Big Cats Facebook group – comes after big cat enthusiast Sharon Larkin-Snowden of Cockermouth extracted ‘Panthera’ DNA from a sheep carcass on an undisclosed Cumbrian hill farm in May. Sightings of feral ‘beast cats’ are nothing new in the county. A Freedom of Information request to Cumbria Constabulary in 2021 revealed nine sightings had been made in the county in the previous five years. Four of the sightings referred to “big cats”, three to “panthers” and one to a “large black cat”.

In other animal news, a dog has fallen off a waterfall, and then been rescued. More from The Westmorland Gazette.

Long read: Jim Watson – A Threlkeld childhood

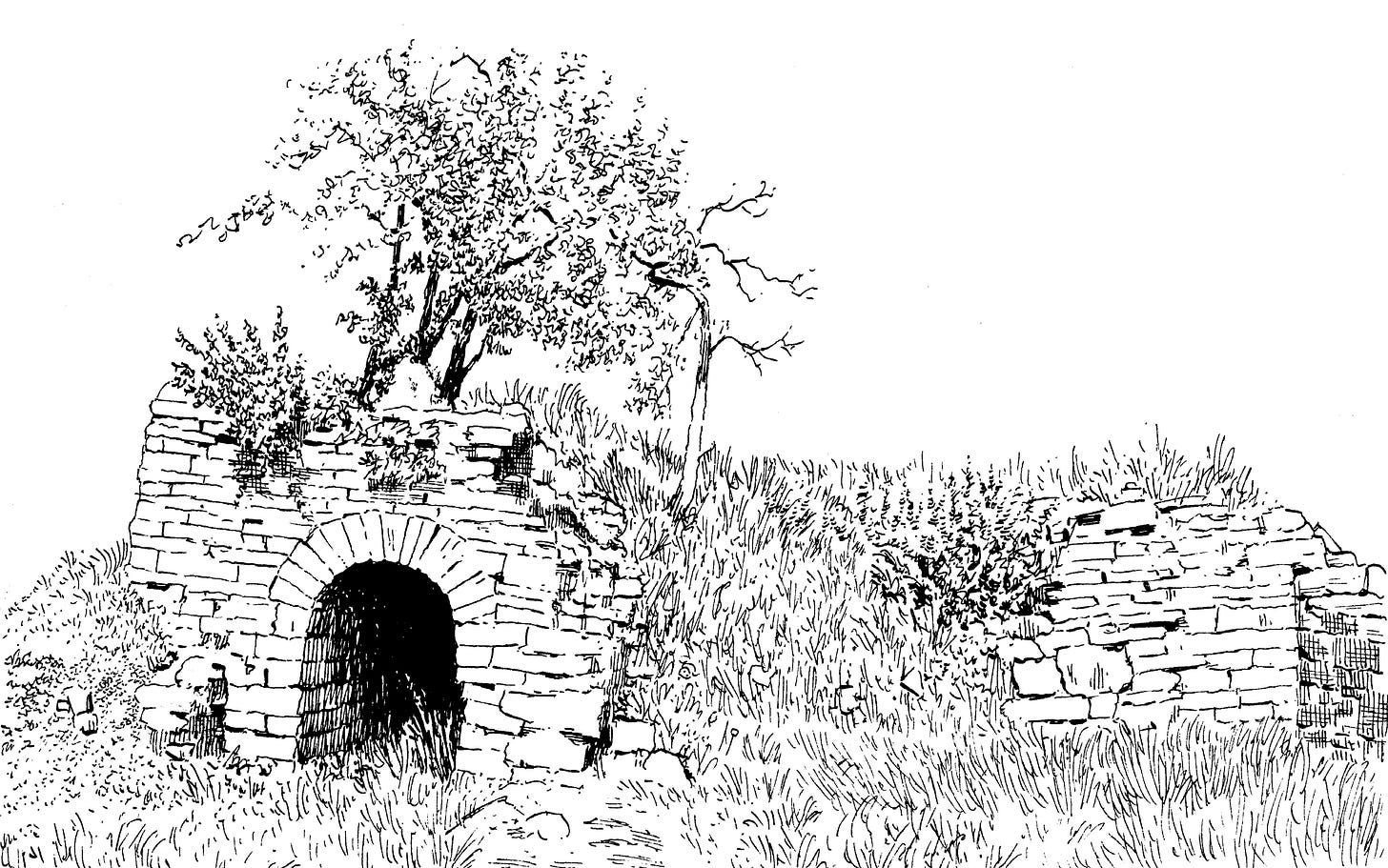

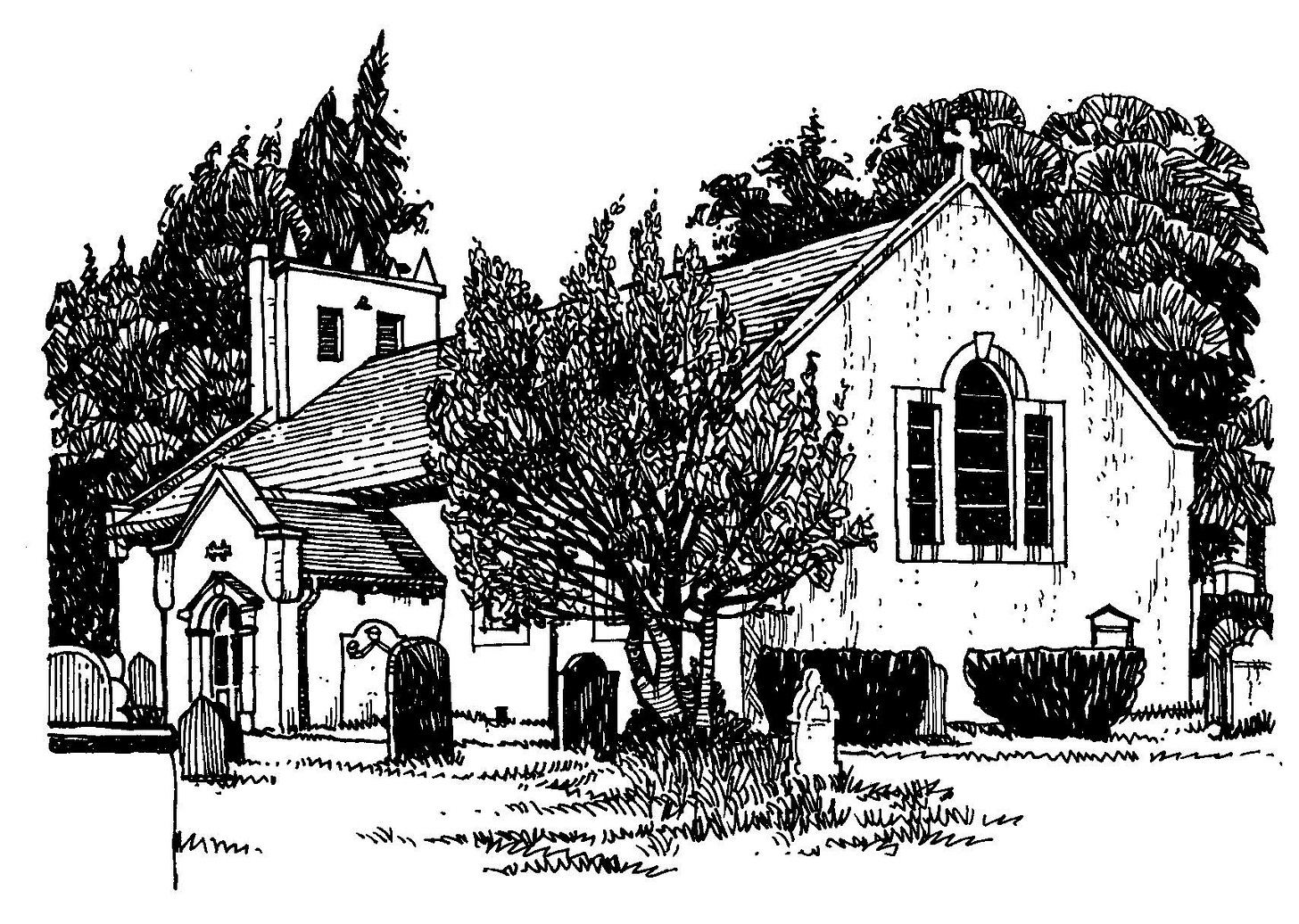

Cartoonist and artist Jim Watson spent the first years of his life in Pooley Bridge before moving to Threlkeld in 1952, aged nine. Here he recounts memories of a Threlkeld childhood and sketches the village he still loves.

Words and images by Jim Watson

We moved into a new council house at Threlkeld in 1952.

Initially we received a tepid welcome from villagers; we were incomers, after all – from Westmorland; another county. When we were accepted, we became part of a vibrant and supportive community. It was a huge lifestyle change for all of us, not least because there were children of my own age – lots of them – something I’d never enjoyed at the sleepy north end of Ullswater.

Our house on Ghyll Bank was one of a dozen semis built on the lower slopes of Blencathra. It seemed vast, with three bedrooms, a bathroom, living room, sitting room, kitchen… and wash house. I started at Threlkeld school, my father ran an upholstery workshop in Keswick and my mother enjoyed her new domain with my two brothers.

Threlkeld was an industrial village – not the tourist honeypot of now. Gategill mine on Blencathra was worked for lead and zinc between 1661 and 1928. At the turn of the century 100 local men were employed there and Threlkeld enjoyed a spectacular – if short-lived – boom. Terraced houses in the village were built using waste from the mine. We used to race bikes – cobbled together from parts found in the village rubbish dump – over the extensive waste tips. They’ve now been removed, the site cleaned up and our bikes returned to the tip.

The Horse & Farrier was the centre of village life. It’s one of the oldest pubs in Cumbria with the inscription ‘CIG 1688’ on the lintel over the front door. The initials are those of Christopher and Grace Irton, then living at Threlkeld Hall. The nearby Salutation Inn, or ‘Sally’, is even older – a former coaching inn dating to 1664.

On the fifth Sunday in Lent the Horse & Farrier used to celebrate ‘Carlin Sunday’, or Passion Sunday, by cooking big pans of carlins for distribution to villagers. Carlins are small dried peas that were soaked in water overnight then boiled until tender. My mother used to send me down to the pub with a big jug to fill. I loved them, and a local rhyme paid tribute to their effectiveness as a laxative (“Carling Sunday” proceeded through “Farting Monday” to, ahem, “Washing Wednesday”).

At Taylor’s Cottages

One day in the early 1950s three of us piled off the school bus anxious to see what was going on at Taylor’s Cottages. A man on the roof was manipulating a large, metal bar construction on a pole attached to the chimney. A cable ran down the roof and into the living room. The owner of the house kept coming out, waving his arms and barking instructions: “Roond a bit... whooa... back a bit... more... la’al bit... no, t’uther way... hod it theeer... reet... no... oh, start agin...!”

We peered through the window at what looked like a tall wooden box on end. A postcard-size section at the top showed a snow storm in flickering light. At the owner’s invitation we were led into the darkened room. After further bellowed instructions, the snowstorm cleared slightly to reveal a stringed puppet.

“Muffin the Mule!” exclaimed the proud owner, thumbs hooked behind his braces: “Television! Whot d’y’ recken?”

Our response was “Aye, au reet,” but once outside, our joint opinion was: “If that’s television it’ll niver catch on.”

‘T’ Crack

Threlkeld was a congenial place. Everyone knew everyone else and considered they knew everything about everyone else. If you did something at one end of the village it was said the other end would know about it before you could walk there.

‘T’ crack’ was a mainstay of village life. On sunny days old ladies would sit at their open front doors eager to chat with anyone passing. Cappie’s petrol station beside the public room was a popular (though not always with Cappie) gathering place at the weekends, where gossip was exchanged and repartee was rife. You were expected to come up with a quick, witty comment or reply to anything said. Passers-by on an afternoon walk would join in, with women as sharp as the men.

Banter goes on in most close communities and helps bind them together. After a professional lifetime of writing gags and striving to make people laugh, I consider my growing up and learning the ropes in Threlkeld to have been an invaluable grounding.

Of concerts and Cydrax

Since opening in 1901, the public room (now the Village Hall) has been a hub of village activity. Dances, bring-and-buy sales, whist drives, WI meetings and children’s Christmas parties were standard events.

We also enjoyed concerts with humorous tales told in local dialect, amateur magicians, pub singers and novelty acts, including one where a man in evening dress played a saw like a violin, and a musical turn from the locally famous Crosthwaite Bell Ringers. The big attraction for us lads was when local girls donned short skirts and tap-danced.

Blencathra Amateur Theatrical Society (BATS) put on plays, both drama and comedy, to packed houses. Villagers would take on surprising new personalities, with the dourest of farmers bringing the house down with an appearance in one of the comedy ‘Whitehall Farces’.

Hunt Balls with accordion bands were also memorable – typically after the pubs shut. Jimmy Shand led a hugely popular dance band at the time. I remember the Canadian Two Step as a stately affair, while the Dashing White Sergeant was the opposite: usually all hell broke out on the dancefloor. Too young to be served alcohol, we started supping Cydrax before dances. Then, after various ‘drunken’ antics, we made the shocking discovery that Cyrdax was… non-alcoholic.

By the late 1950s rock and roll was beginning to be heard in our part of the outback, so we organised a youth club in the public room where we could play records and jive – Cydrax-free.

Blencathra

My first mountain epiphany occurred when I was about eight years old on a train from Penrith to Keswick Bank Holiday Sports with my father. Beyond Penruddock station the train passed through a cutting then suddenly burst onto the open fellside – a perfect viewpoint for the grandeur of Blencathra across the valley. Used to the benign hills around Pooley Bridge, I had never seen a mountain that looked so awesome. It was unimaginable then that two years later I would live at its foot.

We called it Saddleback. Everyone in the village did. Blencathra was the visitors’ name. We thought climbers were a bit odd, travelling all the way to Threlkeld just to climb Saddleback – few villagers ever did.

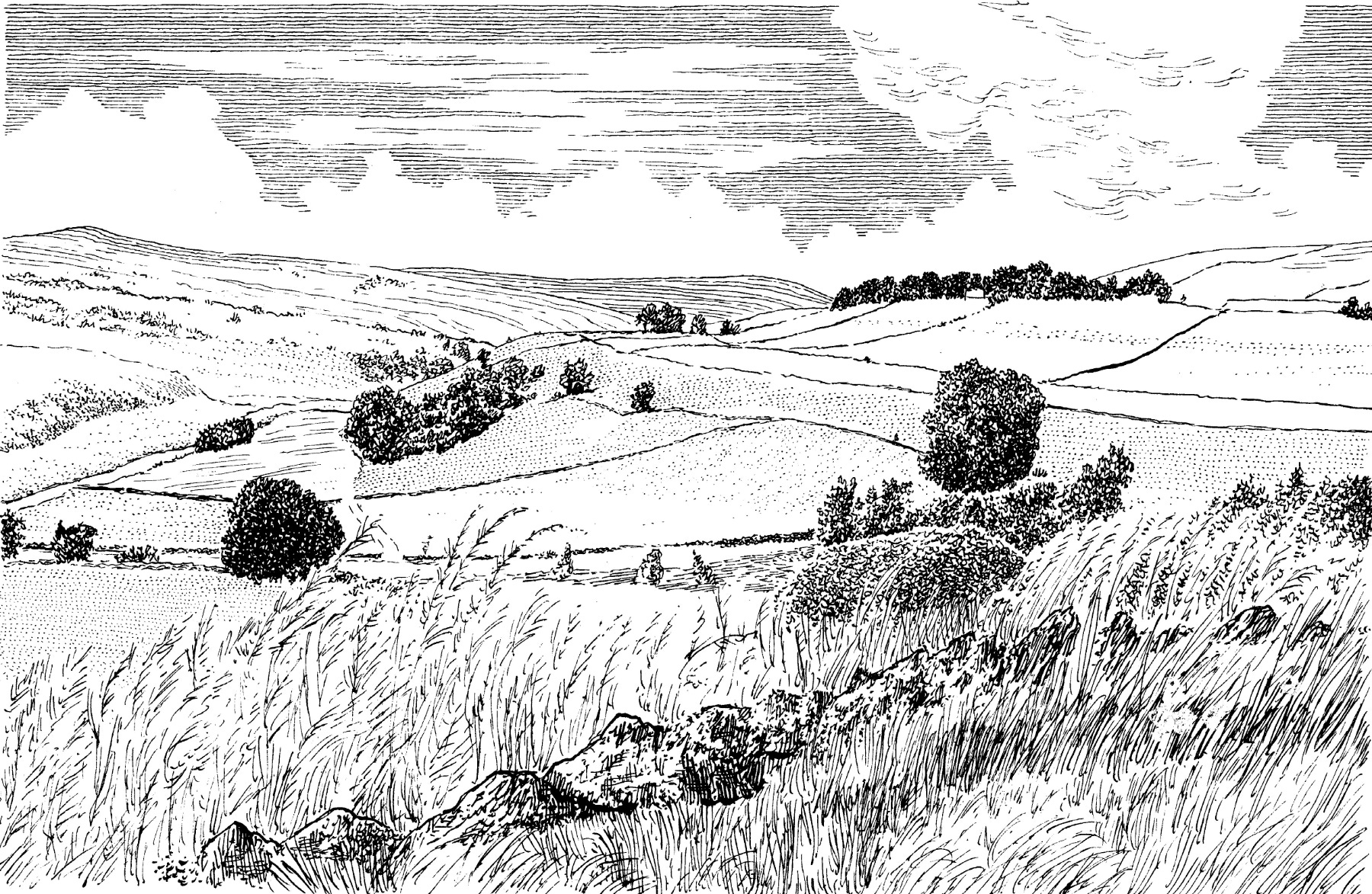

The glory of Blencathra lies in its trio of spurs – narrow ridges that leave the shattered scree of the main mountain, spreading to form substantial buttresses that drop into the fields of the valley. Between the spurs are rocky ravines, each with a beck, each a delight for a fraught teenager to explore.

I’ve never thought of Blencathra as a challenge to conquer; rather the opposite. Like the bridge at Pooley Bridge, it has been a friend – a sanctuary from challenges elsewhere. I loved to sit on the slopes of Gategill Fell alone with my thoughts, looking across the village to St John’s in the Vale and Helvellyn.

Nowadays, travelling east on the A66 to visit my old haunts, distant Saddleback is often as misty as my eyes are when I first see it, telling me I’m home.

This excerpt is taken from Jim’s book My Lakeland: A local lad’s illustrated life, available from Inspired by Lakeland.

Striding out: Mark Richards’ walk of the month

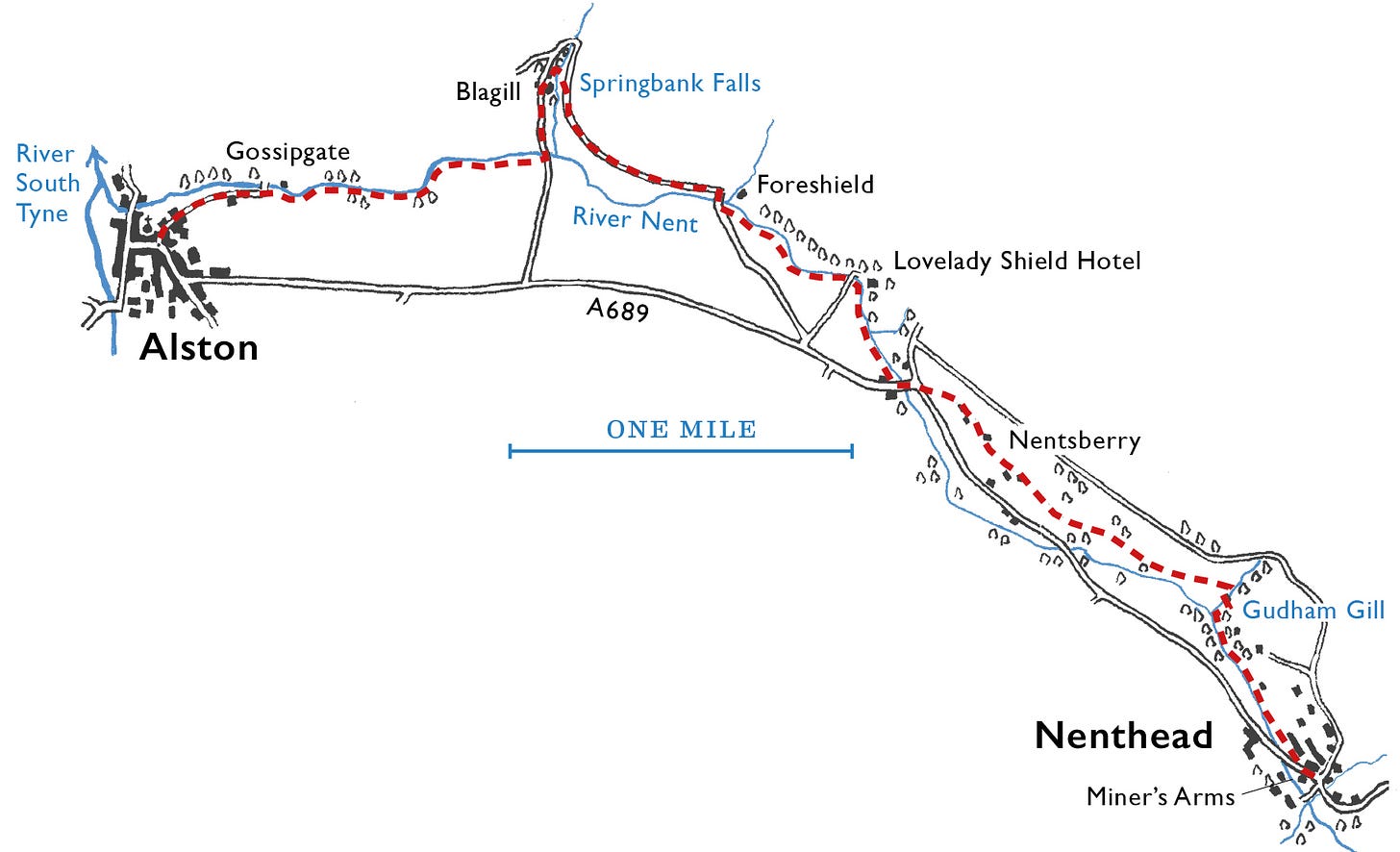

Isaac’s Tea Trail – Nenthead to Alston – 5.6 miles, 375ft ascent

The call of curlew soundtracks this end of summer wander in the footsteps of lives and industry past.

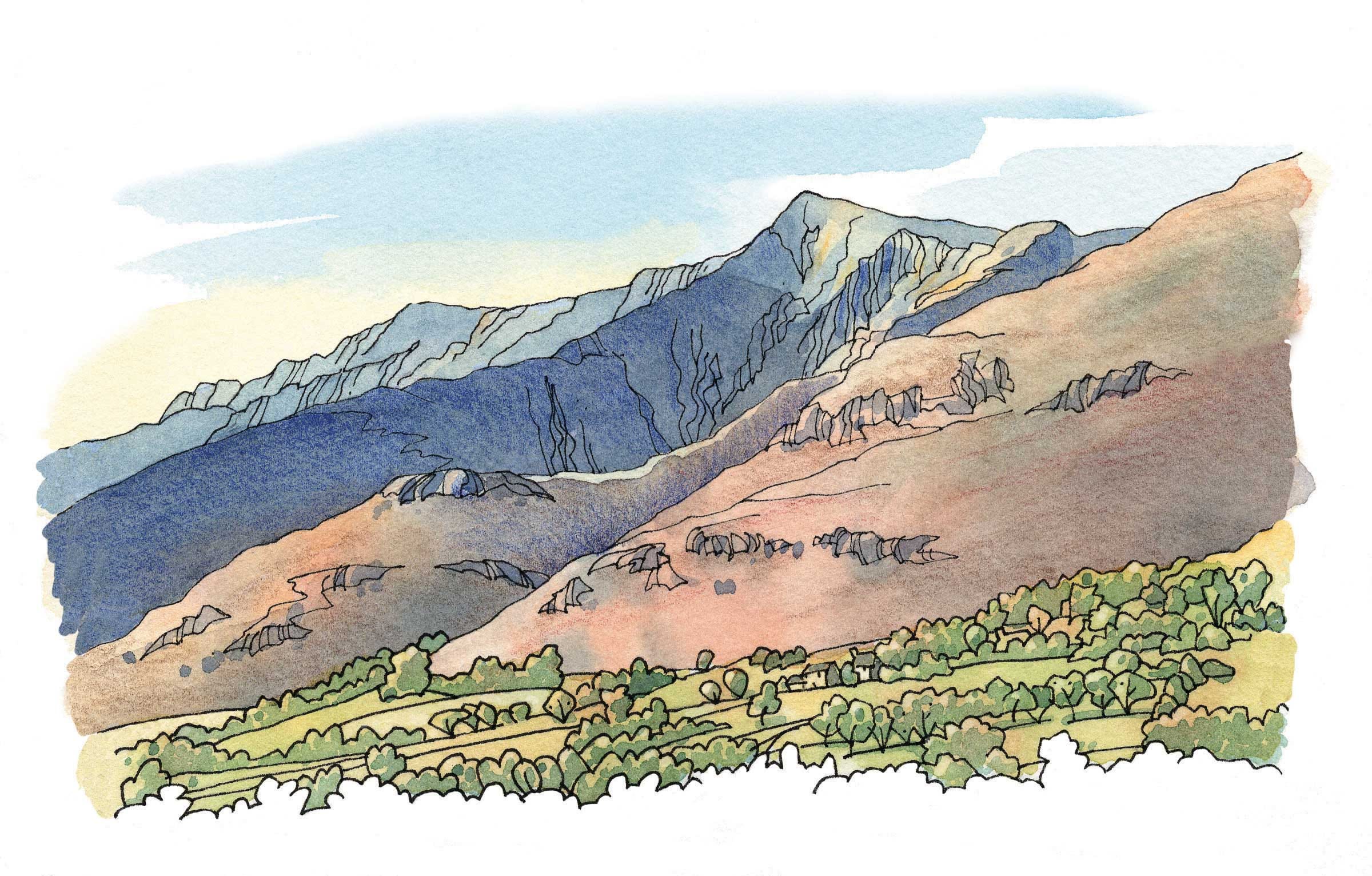

Westmorland, in its latest guise, embraces the portion of historic Cumberland that quirkily lies to the east of the Pennine watershed. At the time of the Norman Conquest, the upper South Tyne valley was apportioned from Northumberland to Carlisle merchants so they might exploit the area’s rich lead reserves, known to have been developed previously by the Romans from their camp at Epiacum.

Those with a taste for solitude will enjoy Isaac’s Tea Trail, a 36-mile walking trail created by Roger Morris, which explores the windswept moors and backwater valleys of East and West Allendale and the South Tyne. The Trail follows in the footsteps of Isaac Holden, an itinerant tea salesman, latterly philanthropist, who wandered these lonely vales in the first half of the 19th century.

The walk sets out from Nenthead, a village that feels far removed from Cumbrian affairs. Indeed marshy Knoutberry Hill that rises above the village is the eastern-most point in the old county of Cumberland. A quiet place now, in its 1880s heyday, Nenthead was a major centre for silver and lead mining, the village housing 2,000, many employed by that giant of Pennine mineral extraction, the Quaker-owned London Lead Company. Now just 400 people live in this isolated upland settlement.

The population decline has not decimated the robust community of Nenthead. Listeners to Countrystride 126 will know of the dynamic energy (and cash) that is being invested into adopting closed pubs as community-owned hubs around the county. In Nenthead, the Miner’s Arms, closed in 2020, is advancing on that journey too, with a gusto generated by 243 shareholders – many of them local – who have raised the required 20% match-funding that will progress them one step closer to buying their pub.

Isaac’s Tea Trail leaves the village north-west, by cottages and a banked garden uniquely decorated with a clustered array of miniature vernacular and high-status town buildings – a model village that includes Big Ben and Graceland, complete with Elvis Presley singing in a loop. This is the work of Lowson Robinson, a former builder who, in retirement, continued his life’s work in miniature. An estate agents’ board suggests the property is up for sale; what future this upland Lilliput?

The path descends beside the landscaped environs of the River Nent and crosses a footbridge spanning the re-entrant Dudham Gill. This is fine walking country, flushes of meadowsweet and rosebay willowherb swaying pink and white in a midsummer’s breeze. From moorland bluffs come the distinct Pennine calls – still in abundance – of oyster catcher and curlew.

Soon after the gill, a horse level accesses the daunting labyrinth of lead levels that burrow into the hill, many east into Northumberland. For ‘horse-level’ read pony haulage; the working life for man and beast in these abandoned adits must have been dark, damp and difficult.

The walk rises and traverses a series of walled pastures overlooking the verdant Nent valley, soon arriving above a caravan park on the site of Haggs Bank – a lead mine that opened in 1690s, and closed within living memory in 1953. At Nentsberry, a cluster of old barns and crumbling dwellings are all that is left of a once distinct community, with its own chapel, pub, hall and school.

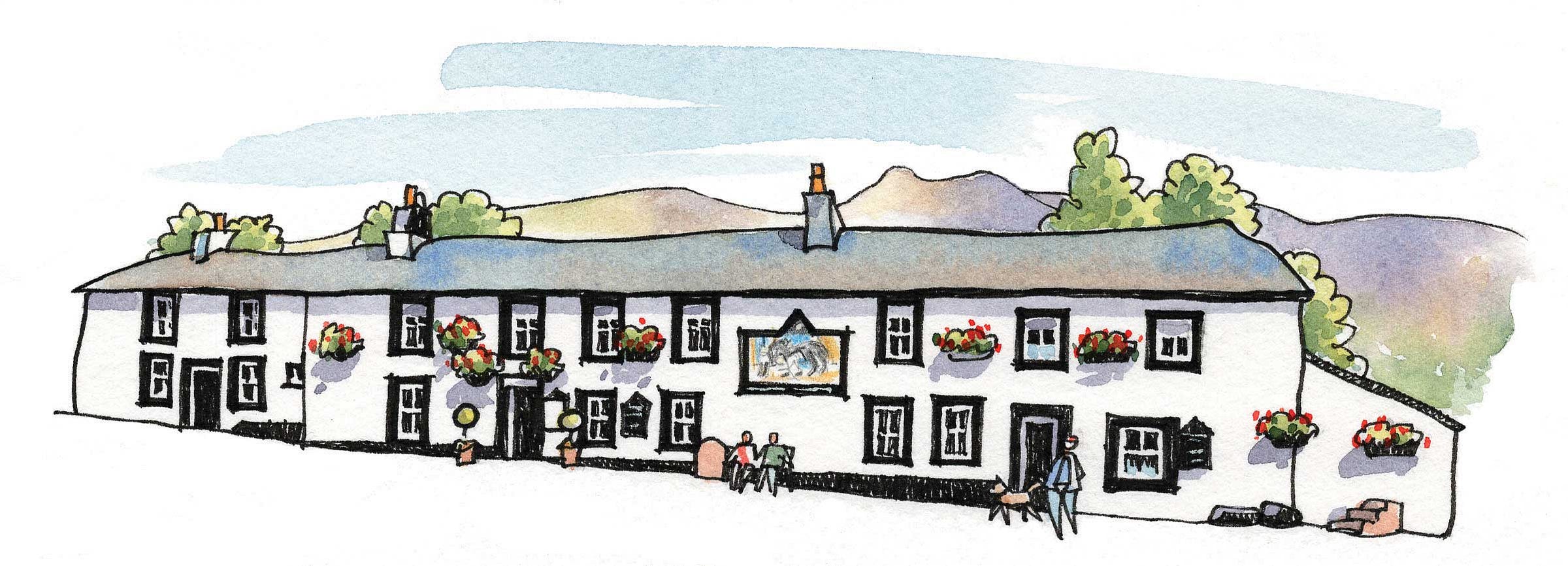

The route descends a flight of steps to a WWI memorial and comes by the handsome one-time hotel of Nent Hall, now closed. Further downriver the Trail passes the bridged entrance to Lovelady Shield, a Georgian hotel of considerable elegance – this one still open; passing walkers may call in for refreshment in the coffee lounge. The romantic name alludes to the site of a 13th century nunnery.

At Foreshield Bridge the walk follows a minor road, climbing gently with fine valley views, before fording Blagill Burn, where a drove-way leads over leaf-draped Springbank Falls.

Thomas Graham farms at Blagill. The adjacent house, Spring Bank, he says, is so named because of a nearby limestone spring of sweet, drinkable water that in past days was collected by bucket. Better this than the sour, peaty output of Blagill Burn.

Just below the falls a large stone barn offers evidence – a gable end and steep pitch of original heather-clad roof – of its earlier incarnation as an early-17th century defensive ‘bastle’.

Bastles were the first stone-built farmhouses, erected when tenants were finally able to transfer the right to farm an area of land to their sons. In earlier, more transient times, such dwellings were timber-built – and as such vulnerable to being razed by Reivers. In a bastle, domestic accommodation was on the first floor, accessed by a wooden ladder that was pulled up when attacks were rumoured. Cattle occupied the ground floor, their body heat warming the rooms above.

The farmhouse alongside has repositioned datestones. First, a square one, inscribed ‘1682’, featuring the initials ‘MAY’; not the month, I am told by Thomas Graham, rather ‘A’ was the surname and ‘M’ and ‘Y’ the first name initials of the farming husband and wife. The second stone, dated 1723, reads ‘NWS’. Two families, names lost in time, immortalised in stonework as part of the building’s long social heritage.

The trail leads down the road to a bridge then re-joins a meadow way beside the Nent. The river name – unique in northern England – is derived from the Welsh nant, meaning ‘valley stream’. The Cheshire town Nantwich has the same root, as does Nant Gwynant near Beddgelert – a quirky tautology. The closing mile switches between pasture and woodland to enter the historic town of Alston by Gossipgate, coming upon the canopied market hall in the sloping central thoroughfare.

Isaac’s Tea Trail is well waymarked and furnished with path infrastructure maintained by the North Pennines National Landscape. The best guidebook is Roger Morris’ A Guide to Isaac’s Tea Trail, downloadable from

Anne Leuchars writes a blog on the walk at

We walked a section of the Tea Trail with both Roger and Anne in Countrystride 83.

You can buy Mark’s Walking the Lake District Fells guides from Cicerone.

Cumbriana: Fairy tales from Eskdale

A column of curiosities, with Alan Cleaver

On wet days (most of this summer) I squirrel myself away in the cosy world of Whitehaven Archive office and while away the hours reading through some of the many hand-written journals that sit forgotten on the shelves. Although many of them are worthy, if dull, occasionally one unearths literary gold, and buried deep in one tome I recently came upon the following heading: “An account of the Ancient Little People, later called Fairies, who lived in the hills of Eskdale and Millom.”

Cumbria was once a stronghold of fairies, and human residents were generally happy to live alongside them. In accounts from around the county fairies are typically described as slightly smaller in stature than ordinary folk – tiny winged beings were the invention of Mr Walt Disney.

The account of fairies in Eskdale and Millom was new to me, and it was written by one Rev. William Salter Sykes, vicar at Millom from 1895 to 1900. In addition to his clerical duties, he was a keen antiquarian.

His hand-written account begins:

“Stories of the Fairies were very difficult to obtain, as the dalesmen were much afraid that they were being made fun of by the enquirer. There is little doubt, however, that the belief they were a real people existed in the dales till quite recent times. At Dalegarth, for example, the corn that had been put ready for flail, which was still in occasional use in my time, was often found threshed in the morning. And the churning at Millom Castle had frequently been finished before the housewife appeared in the morning.”

Both tales show fairies as generally benevolent beings, helping their human neighbours with domestic tasks and agricultural work. The final line refers to the legend of a ‘hobthross’ – a house fairy – that lived at Millom Castle (now a part-ruin, part private residence).

The hobthross would lend a hand to castle residents as long as he was not paid for his kindness. This ancient idea – strange to us today – stems from the religious notion that one should not seek reward or praise for good works. Part-way through a cold winter – so the tale goes – a member of the household made the hobthross a new coat as a sign of gratitude, at which point the fairy departed for good with this sign-off: “Hobthross has got a new coat and a new hood. He'll never do more good”.

Sykes’ account of Eskdale fairies isn’t all sweetness and light; the little folk could be mischievous, too, subjecting humans to “Elfin tricks”. Indeed so tiresome did some of the “Ancient Little People” become that villagers might “lay a knife across the doorstep” to guard their property or “make a sound like the sharpening of knives” to ward off possible malevolence.

So… mixed reports of help and hindrance, which reflects wider stories of fairies throughout Cumberland and Westmorland. If you want to read Sykes' account, I have published it online at lakedistrictletters.blogspot.com. And to seek out Westmorland fairies for yourself, try visiting the charming Fairy Drinking Well on Sweden Bridge Lane, near Ambleside, grid reference: NY 37977 06267.

‘The Pimp’*: Five of the best…

Long distance footpaths that spend time in Cumbria

As picked by Dave Felton

#5: A Dales High Way

Chris and Tony Grogan’s 90-mile journey from Saltaire in West Yorkshire to Appleby is that rare thing in the world of long distance walking: a trail that delivers scenically pretty much every step of the way. Unlike the classic – and ever-popular – Dales Way, which generally sticks to the riverside lowlands, the High Way relishes more adventurous ways-less-trod, with particularly memorable sections skirting Attermire Scar and Whernside via beautifully named Boot of the Wold (the gentle mile or so along Hale Lane from Feizor also merits mention).

The High Way enters Cumbria via Dentdale – the valley that mass tourism forgot – before making an ambitious crossing of the Howgills and a final-fling traverse over the remarkable limestone pavements of Asby Scar. Some long distance walking routes are made-by-committee compromises; the Dales High Way is conceived by walkers for walkers, and is one of the finest long-distance trails in the north country.

#4: The Cumbria Way

The only one of these choices that sticks within the county limits, in peak season you might meet two-dozen or more wayfarers on each leg. The popular 72 mile route from Ulverston to Carlisle – and typically walked that way – is… solid enough, without being remarkable.

The opening stretch from Ulverston to Coniston – where Lakeland opens in majestic panorama on the meandering miles through the Blawith Fells – offers a tantalising foretaste of drama to come. From there, Great Langdale beckons, before the trail swings north via the glacial valleys of Mickleden and Langstrath. Derwent Water’s west shore is one of Lakeland’s loveliest waterside ways, and the day’s traverse through the Back o’Skidda’ ensures landscape variety all the way to picture-perfect Caldbeck.

It’s the final day that lets the trail down, a fiddly meadow and riverside foliage-fight that cannot live up to the highlights of earlier miles. As such, the wise wayfarer travels south from Carlisle.

#3: A Coast to Coast Walk

If Alfred Wainwright’s greatest gift to the fell-walker was his seven-volume Pictorial Guides, the second best was surely his Coast to Coast Walk. The route from St. Bees on the west coast to Robin Hood's Bay on the east, as described in his book of the same name, was as much AW’s attempt to better the Pennine Way (“I finished the Pennine Way with relief, the Coast to Coast Walk with regret,”) as a love-letter to his beloved northern landscapes. Visit St Bees on a summer’s day and you’ll find a steady stream of fresh-faced walkers dipping their boots in the North Sea as they set out north before swinging east.

The walk spends just over a third of its 192 miles in Cumbria, with highlights including the clifftop wander to St Bees Head, the craggy drama of Upper Ennerdale, the succession of mountain valleys through to Patterdale, the isolation of Riggindale and the wildflower meadows of Ravenstonedale.

There was always a tension between AW’s stated intention not to craft an “official route” across the country and his walk becoming the de facto non-official route across the country – and a phenomenally popular one at that.

In a further ironic twist, 50 years after writing in his Coast to Coast Walk end-notes that “‘official’ long distance footpaths” are not “wholly to be commended,” the Ex-Fellwanderer’s trail is in the final stages of being designated as… an official National Trail.

#2: The Pennine Way

Scenic high points are hard-won on England’s oldest National Trail – Tom Stephenson’s ‘long green trail’, opened in 1965. The 268 mile path, from Edale in the Peak District to Kirk Yetholm, just inside the Scottish border, is a tough proposition. Even if the notorious peat hags that defined the Trail’s early years are a (flagged) thing of the past, the Pennine weather and the exposed upland miles soon take their toll, with more than a few folk abandoning their trek north somewhere around Longdendale.

Although there’s an austere kind of satisfaction to be found crossing big-sky gritstone country, the scenery improves dramatically after the ‘muck and manure’ transition of Aire Gap, where Malham Cove presents the first of many wow moments. After crossing soggy Bowes Moor (and an obligatory pint at the Tan Hill Inn), the Trail flirts with Cumbria’s eastern border, striding through lonely Baldersdale to begin the two loveliest days of the walk: the wildflower-bounty foray into Upper Teesdale past the great Whin Sill falls of High and Low Force, and the wide swing west to enter Cumbria at the geological wonder of High Cup. Happy memories can be recalled – and made – at The Stag Inn, Dufton, before the long haul over Cross Fell, high point of the Pennines.

Although the Pennine Way does not see anywhere near the number of walkers it did in its rambling heydey, it is the godfather of British walking trails, with a historic heft and political importance that deserves every long distance walker’s attention.

#1: A Pennine Journey

…and the number one spot goes to A Pennine Journey, David and Heather Pitt’s adaptation of a 211-mile walk Wainwright undertook in the build-up to war, as recorded in AW’s superb – and underrated – book A Pennine Journey: The Story of a Long Walk in 1938.

Unlike other walks in this list, A Pennine Journey is a circular route, usually completed in a couple of weeks. It heads up-country on the east side of the Pennines, exploring the far-from-the-madding-crowd Durham Dales. Hitting Hadrian’s Wall – AW’s original goal – the Journey swings west, sharing miles with the Hadrian’s Wall Path, then the Pennine Way, as it enters Cumbria via Alston for the homeward miles.

Wainwright himself loses heart on the long southern leg. Persistent rain souring his mood, he anguishes for half a chapter over abandonment. But the miles through Cumbria are a joy every step of the way, from the bluebell woods of Flakebridge to the lofty traverse of Lady Anne’s High Way into Mallerstang (as featured in Mark’s first ‘Striding Out’ column).

Unlike other paths on this list, A Pennine Journey remains a walk few undertake, but that’s a large part of its understated charm, which enjoys scenic variety day after day. The Durham Dales are a world apart from their Yorkshire (or Westmorland) equivalents – out-of-the-way valleys ignored by the tourist hordes – the Dales sections are a delight, and the Cumbrian miles a backwater pleasure. Even better? One can follow AW’s walking narrative in real-time as he evokes a world on the brink of seismic change. Consider it the finest long-distance walk on this list.

Dave has kept photo diaries of many long distance walks. They can be found at uklongdistancefootpaths.com

* For the avoidance of doubt, ‘pimp’ is five in Cumbrian dialect.

Postcard from the past, as chosen by Nick Thorne

‘Bank Holiday at Grange’, postmarked 1910, Grange-over-Sands

Writes Nick:

“This month I’ve chosen the postcard ‘Bank Holiday at Grange’. I cannot be sure of the date of issue, but it’s pre-1910 as the postmark date is 1 August, 1910. I’ve chosen this for a few reasons, the main one being that it shows a way of holiday life in Grange-over-Sands that simply doesn’t exist any more. That’s always a recipe for nostalgia. Secondly, because of the message on the back, written by someone who plainly didn’t want to be here! The text reads as follows:

“Hope you are having a nice time. We leave here tomorrow – for where I don’t know. I think I would rather have been at Leeds than here. It is very nice for some things, but not for others. Excuse pencil, I have written this in the waiting rooms at the Station. I am supposed to be on the Prom getting the sea breeze. While you are so busy don’t forget your absent brethren.”

Nick maintains the superb Grange-over-Sands history and heritage website at

https://grangeoversandshistory.weebly.com, which includes a range of historic postcards.

We walked and talked with Nick on Countrystride #62.